Strange Loop 2019 - Recreating forgotten programming languages, for art!

Overview

The early beginnings of computer graphics in the 1960s saw the birth of a number programming languages that were created specifically for making animations and graphics. Almost all of them are now obsolete and mostly forgotten. However, back then, many of these languages cutting-edge and made possible the completely new field of making art with computers. A prolific example of this was Bell Labs' BEFLIX, a language created to make animations using a microfilm plotter.

Computer art

Computer art can be defined "any art in which computers play a role in production or display of the artwork". This talk focuses on the birth of computer art, specially the era of the 1950s to 1970s.

Context matters! What where computers like back then? Who was creating this pieces of art? What equipment did they use? Technology and intentions shape the artwork.

Computers back then

The IBM 7090 Data Processing System was introduced in 1959. It cost a measly $ 3,000,000.

Computers were mostly restricted to research facilities, big corporations and the military, thus limiting the number of people who had access to them.

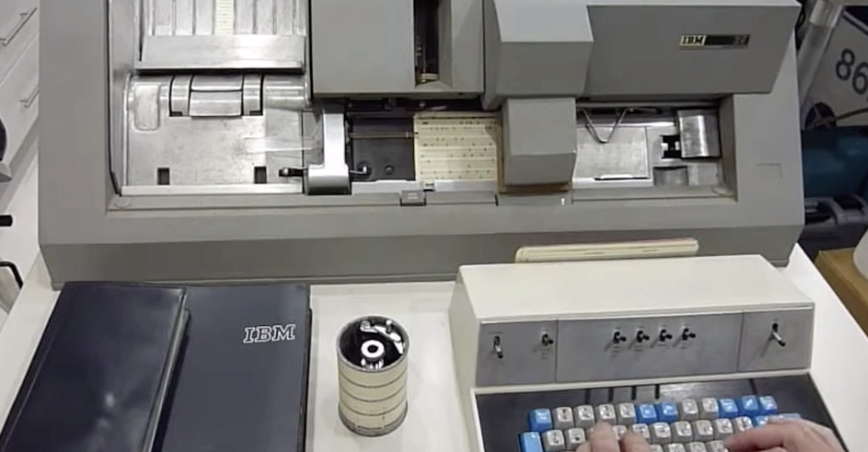

Punch cards

Source: CuriousMarc on youtube

Source: CuriousMarc on youtube

Computer were usually written on punch cards, and you would often have to wait a day or two for your program to be run by the operator because someone else's job was in the queue.

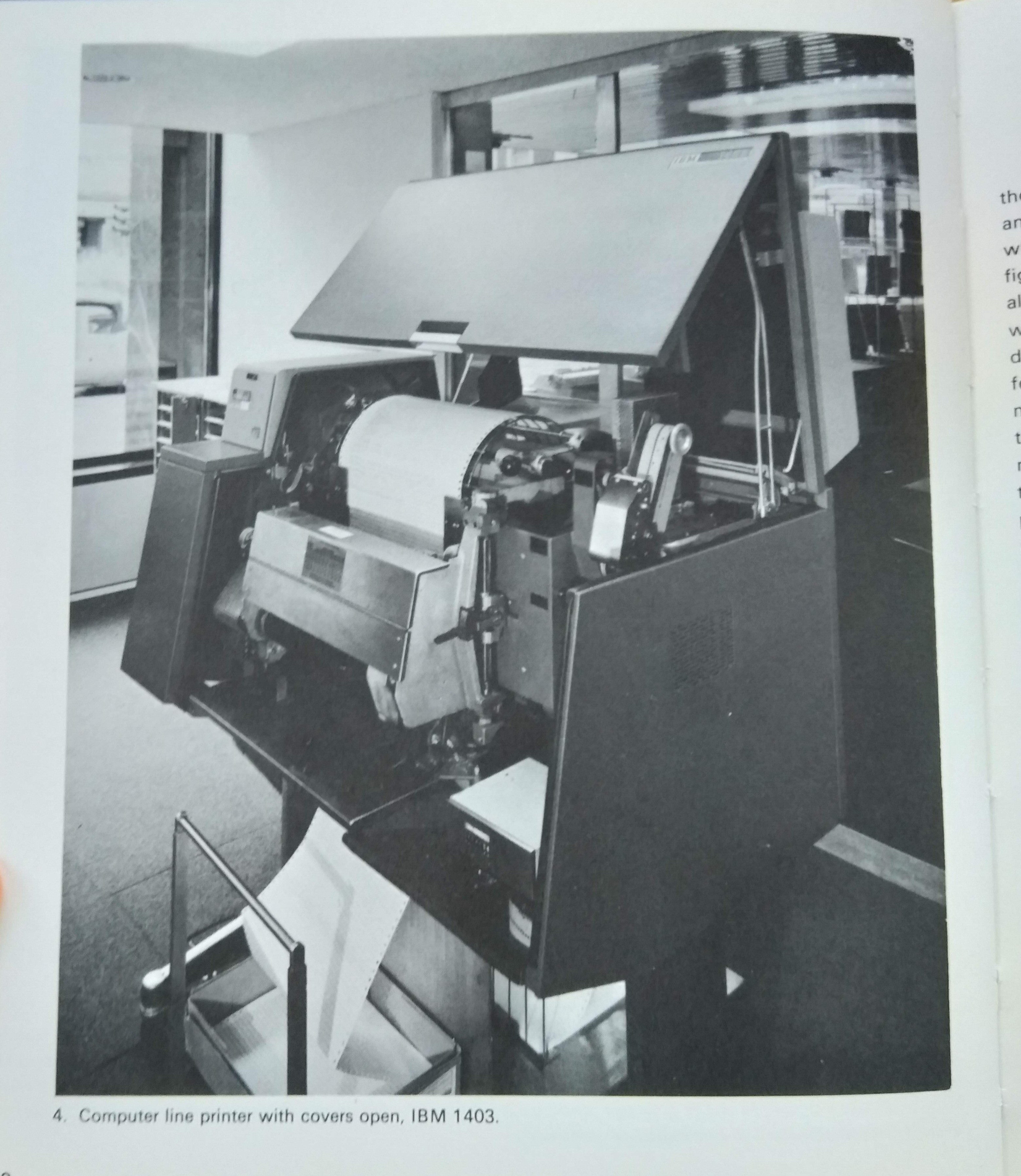

Output devices

Program outputs could be output on a printer. Common were line printers, which use a drum with a restricted character set. They were fast and loud.

IBM 1403 line printer (Source: The Computer in Art, Jasia Reichdart, 1971)

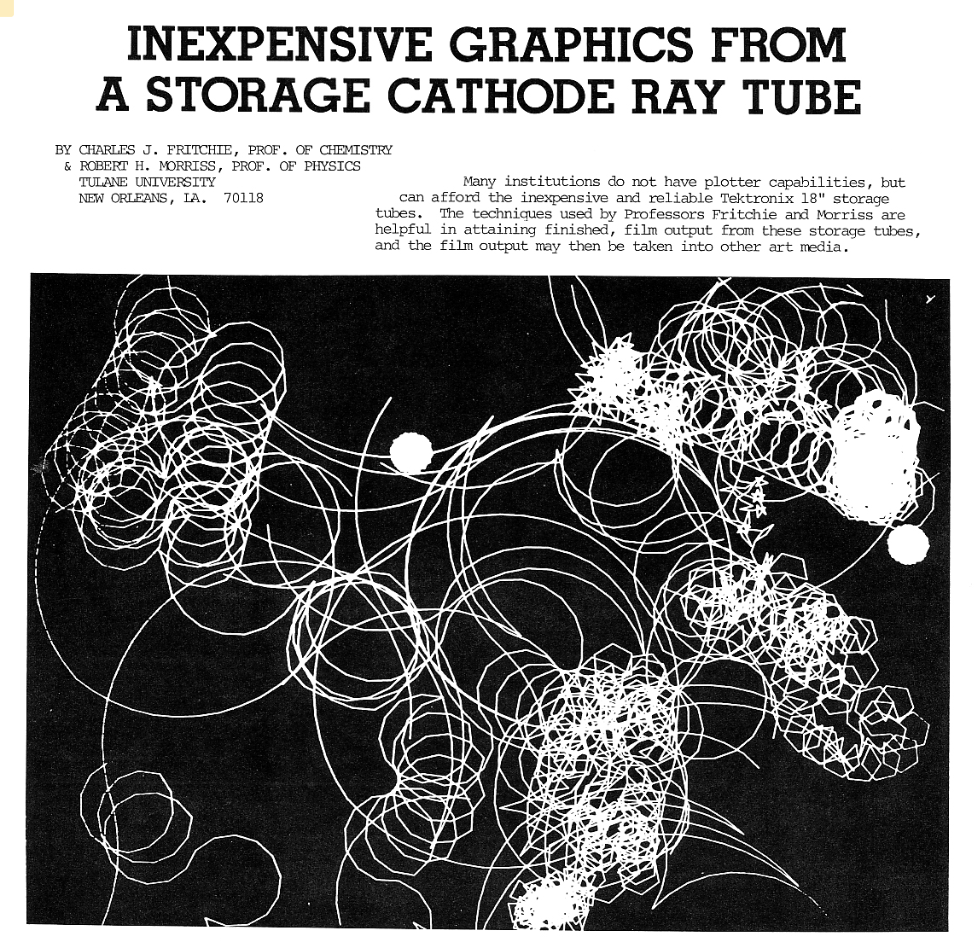

Another output device was the cathode ray tube display.

An example of its use can be found in Experiments in Motion Graphics by John Whitney, 1968

Stromberg Carlson 4020 microfilm recorder (source: chilton-computing.org.uk

Electronic/microfilm plotters are used to print characters to microfilm. They are usually not made to plots graphics or geometric forms.

CalComp 565, early drum plotter introduced in 1959 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Also, mechanical plotters, basically robot drawers with a pen and motors moving the pen, making them perfect for intricate drawings like graphs.

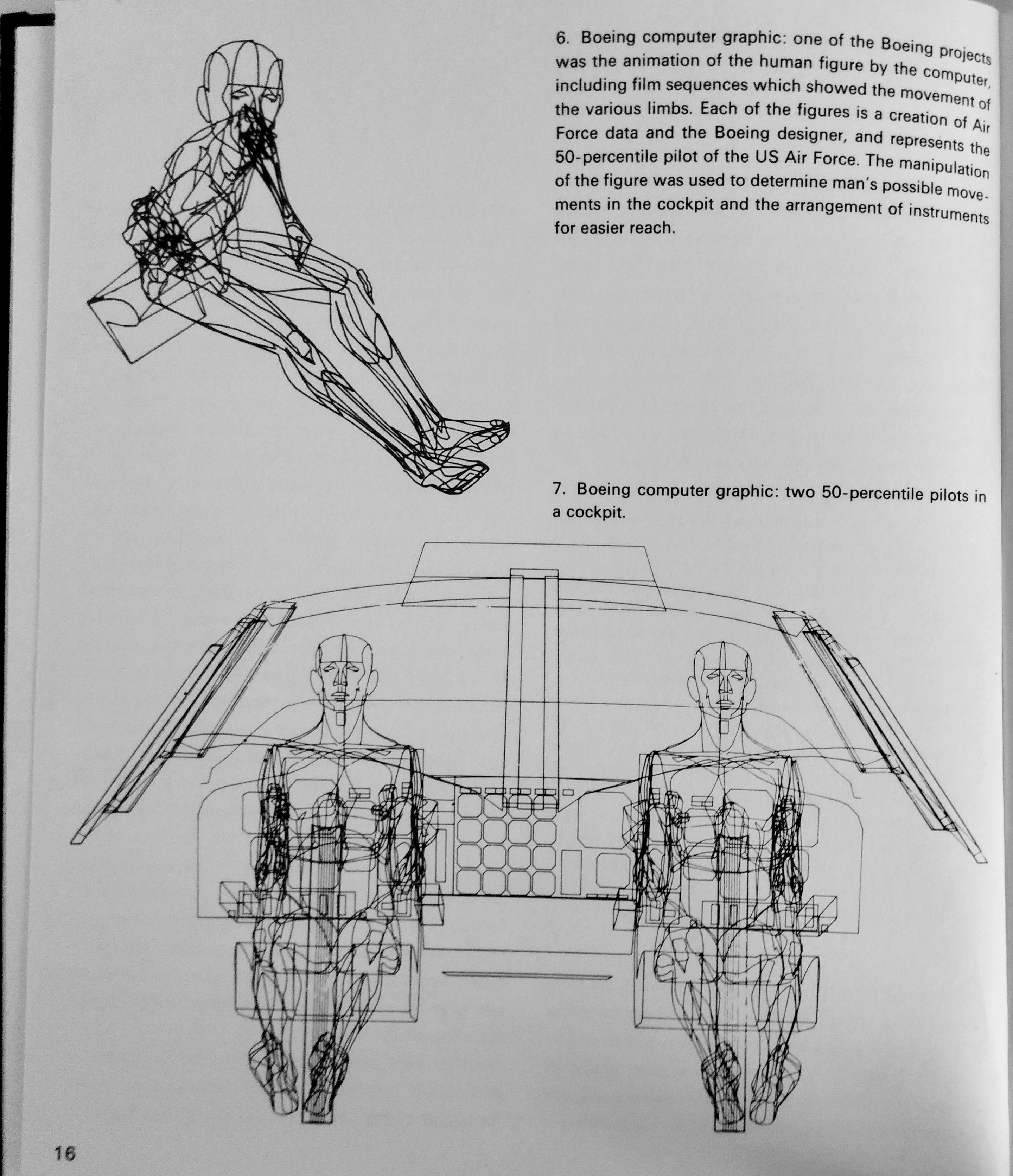

Who used these computers?

Computers were mainly used for scientific and mathematical applications. Boeing was a real pioneer in computer graphics (and actually coined the term). The company used computers to simulate the position of pilots in the cockpit to determine the layout of the control console.

Source: The Computer in Art by Jasia Reichdart, 1971

Bell Labs was another hotbed of computer graphics research, and made one of the very first computer generated films. This was revolutionary, because you would have to previously draw every animation frame by hand.

Example: Simulation of atwo-gyro gravity gradient attitute control system (source)

Retro computer art

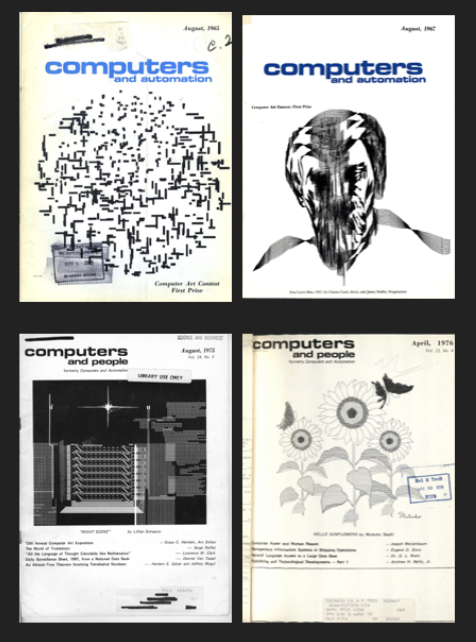

To find examples of retro computer art, we can look at mid-century computer magazines.

Computers and Automation - The wired of back then, edited by Edmund Berkeley

The editors of Computers and Automation were the very first people who ran a computer art competition in 1963. Due to the available technology, a lot of it was line based, geometric, black and white. The magazine ran an annual august art issue, directed by Grace C. Hertlein.

Source: recodeproject.com

Hertlein went on to publish another magazine: Computer Graphics and Art, which is a great magazine to look at what cutting edge computer art was back then.

Reverse-engineering old computer art

The artworks were made with limited technology, but look really cool, making you wonder how they were made. Sher Minn thus went onto a little rabbit hole to figure out how they were made, and recreate them with more modern programming languages.

Tesselation variations of the Four Bugs Problem pattern (twitter.com/piratefsh)

Challenges

- No source code

- Pieces were often published with the final output. If you are lucky, you might get a short dscription.

- Made with defunct platforms and languages.

This raises an interesting question: How do programming languages influence the world?

Looking at two art programming languages

ART 1 - Language for making graphics

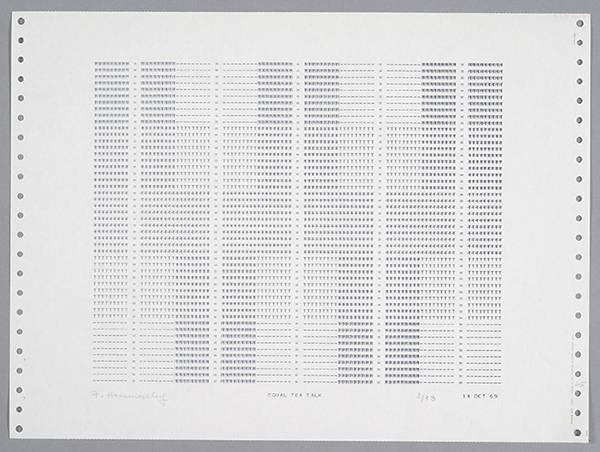

Equal Tea Talk by Frederick Hammersley, 1969 (source)

Because of the low resolution character output, the artwork has a lot of texture and gradients, making it quite interesting to look at. It was printed using a line printers. Line printers print line by line with a very limited character set. Example of a drum of a line printer. Really fast and really loud.

These graphics were made with a language called "ART 1", made by Katherine Nash and Richard Williams at University of New Mexico. The graphics are made by printing 2 blocks of simple characters on top of each other. They were EBCDIC characters, these days we have something similar with ASCII.

ART 1 artworks are good examples of art created with the available technology of the time.

What was it like working with the language? It is really hard to find documentation about it. Luckily, there are a few lines of information about the language in the book "The Computer in Art" by Jasia Reichdart, 1971, which documents the zeitgeist of computer graphics back then.

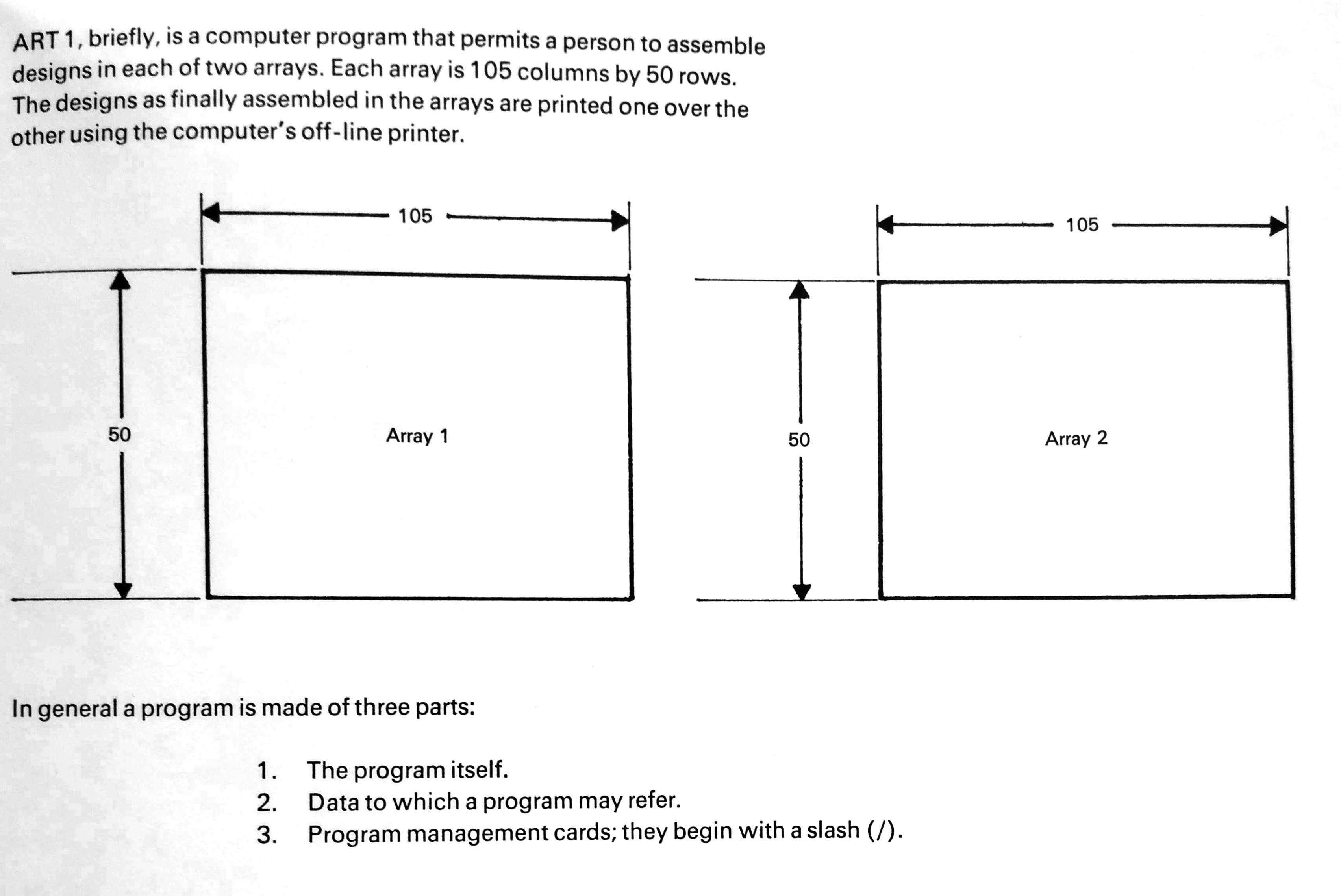

The ART 1 Language - The Computer in Art, Jasia Reichdart, 1971

The language provides 2 arrays, each by 105x50 characters. A simple program can draw fundamental shapes (rectangles, triangles, ellipses) into each array. The arrays would then be printed on top of each other.

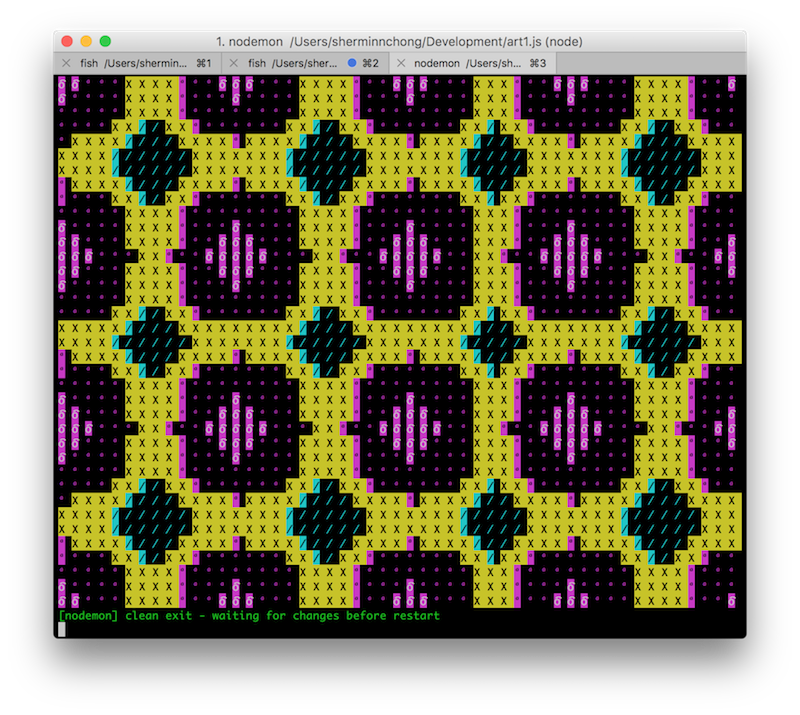

Sher Minn Wrote an implementation of ART 1 in javascript, which was easier route than writing an actual interpreter.

Problem #1: don't own a printer, and today's printer don't work the same as line printers.

Solution: use the next best thing, use the terminal.

Problem #2: How to do overlapping text with the terminal?

Solution: Make the most of the available character set, and use diacritical marks to achieve overlapping.

The best thing is that you can use emojis!

Here is a simple example with squares.

const { init, rect, print } = require("../src/art1");

(function main() {

const width = 20;

const height = 12;

const c = init({

width,

height,

symbol1: ".",

ncol: 1,

symbol2: "",

mcol: 1

});

c.arr1 = rect(c.arr1, {

r: 4,

c: 8,

nr: 4,

nc: 4,

symbol: "o"

});

c.arr2 = rect(c.arr2, {

r: 2,

c: 6,

nr: 4,

nc: 4,

symbol: "\u20de"

});

console.log(print(c, " "));

})();How to draw lines

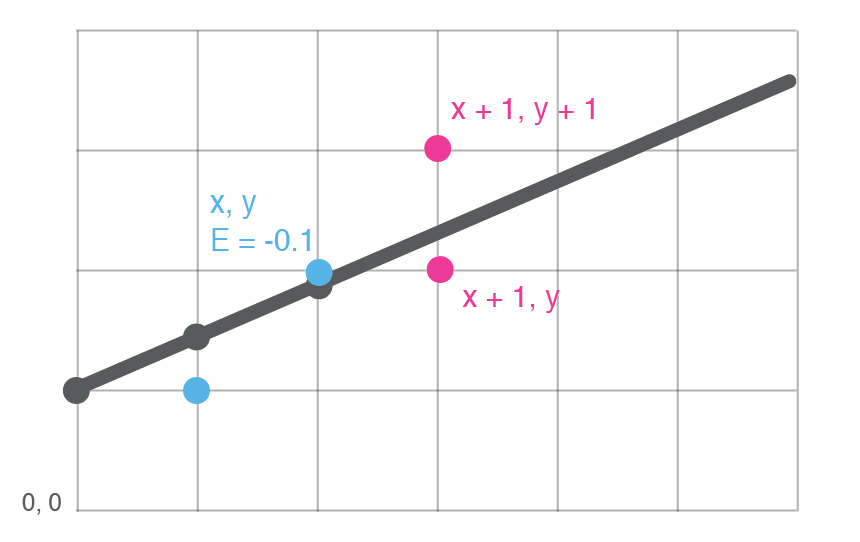

One step of the Bresenham line algorithm

An interesting side-problem was to figure out how to draw lines, using the Bresenham algorithm. The algorithm figures out which pixel to next print out. At each point, it can either go right, or up (in the case of a diagonal upwards line). The algorithm accumulates the error and makes the decision to print the pixel with the lowest error.

Languages for making movies

BEFLIX - A language for moving pictures

A computer technique for the production of animated mvoies (AT&T Tech Channel on Youtube)

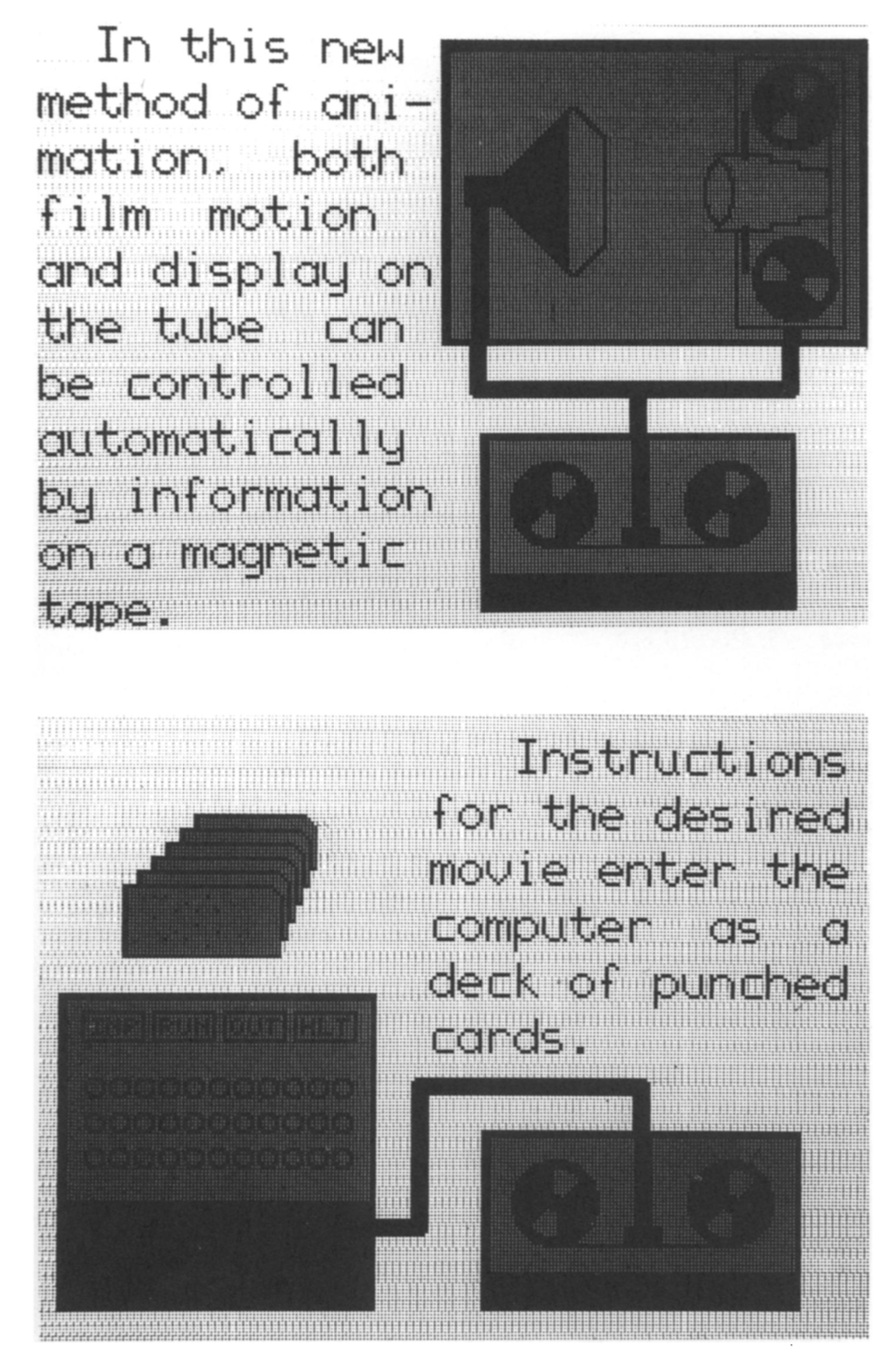

Kenneth Knowlton at AT&T Bell Labs made a silent video about how to make movies with computers, in which he describes a language called BEFLIX (Bell flicks), based on FORTRAN macros.

Source: Computer-Generated Movies, Designs and Diagrams by Ken Knowlton, Design Quarterly, No. 66/67

Instructions are written on punch cards, executed by the IBM 7090, and output on the SC 4020 microfilm plotter. Microfilm plotters were made to output text, not really graphics, so the graphics are based on character sets.

BEFLIX had a really hard learning curve, and a lot of non-technical people were interested in it, which led Knowlton to create a language called EXPLOR (EXplicitly defined Patterns, Local Operations, and Randomness), which was explicitly created for artistic purposes, working with artists in residence.

EXPLOR

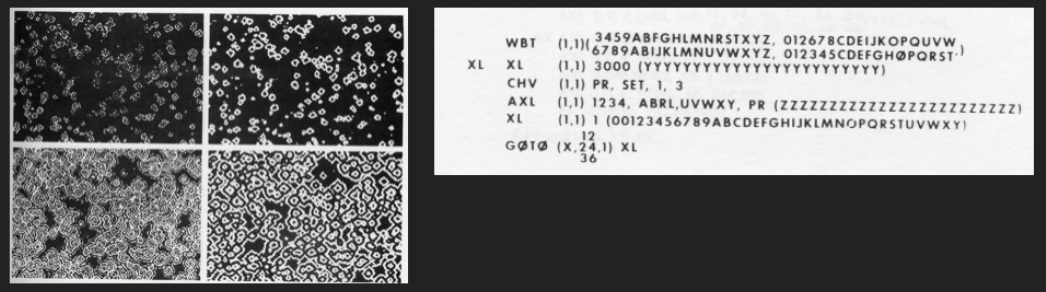

EXPLOR is an interesting language because it's a probabilistic, transliteration based language.

Mapping cells to colors

WBT (n, p) (whites, blacks, twinkles)It works with a grid of 340x240 cells. Each cell can be mapped to colors.

Probabilistic indicator

The (n,p) is a probabilistic indicator. Execute this like every n-th time,

with a probability of 1/p. You can invert the statement with (X,50,1) (execute except for the 50th, 100th, ...) time.

Transliteration

XL (n,p) q (xlit)

# for example

XL (2, 1) 3 (AB, CD)Every 2nd time this line is reached, updated one third of the adjacent cells, replacing A with B, and C with D.

Adjacency-condition transliteration

AXL (n,p) nums, dirs, chst, q(xlit)

# for example

AXL (1,4) 234, NESW, ABCD, 5(56,78)Every 4th time, if there are 2, 3 or 4 neighbors either North, East, West or South, whose values are A, B, C or D, with a probibility of 5th, replace 5 with 6 and 7 with 8.

Examples

This programming languages could be used to simulate phosphenes.

Simulation of Expanding Fringe Visual Phosphenes

Simulation of Expanding Fringe Visual Phosphenes

Sher Minn is still working on an implementation, and invites people to contact her if interested.

Why recreate forgotten programming languages?

As programmers, we are often more focused on the new. But looking at what has been tried, where we come from gives us an appreciation for what we have today.