GopherCon 2019 - Go Module Proxy: Life of a query

Royce Miller for the GopherCon 2019 Liveblog

Presenter: Katie Hockman

Liveblogger: Royce Miller

Overview

The Go team has built a module mirror and checksum database, which adds reliability and security to the Go ecosystem. This talk discusses the technical details of authenticated module proxies, following the journey of a request through the go command, proxy, and checksum database.

Introduction

Katie Hockman, a software engineer at Google working on the Go Open Source team in NYC, is part of the group of engineers building the Go module mirror and checksum database.

Katie's talk is about some new things that are happening around package management and authentication in Go. She wants to help you understand how these things work at a more tangible level.

You may find the slides to Katie's talk here.

Some Background

Katie absolutely adores dogs.

She wanted to create a set of Go packages that help other people be better dog owners. If dogs are happy, Katie's happy.

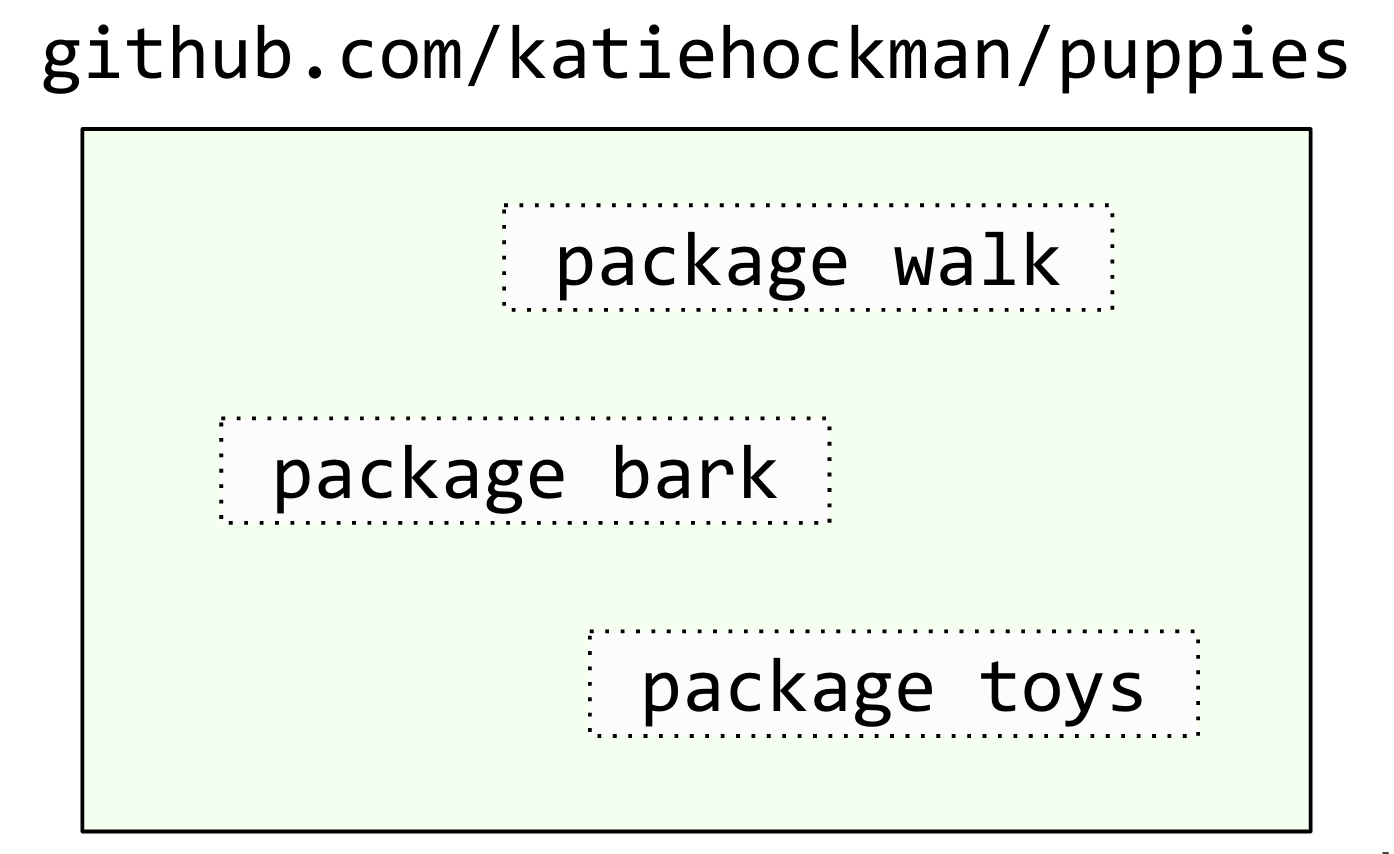

She begins to create a new repository on GitHub, and starts creating Go packages for all of the source code that she wants to provide.

- She created walk, a package that can algorithmically decide the best dog walking route in your neighborhood.

- She then created bark. A package that can tell you what your dog is thinking based on the audio you provide from their bark.

- Finally, she created toys. A package that reminds you to buy a new toy for your dog every week, so he never gets bored.

There are a lot of APIs the code has to depend on though. She needs dependencies for storage, audio processing, and Maps APIs.

But she has some concerns:

- She's worried she'll have challenges with non-reproducible builds. She's relying on a brand new API endpoint for the Maps Service that she's using. If the people that import her package are using an old version of that API, then things are going to break for them, and she has no way of guaranteeing that their builds will be consistent.

- The owner of the audio detection package that she depends on might just get fed up with managing it, and decide to pull the code from github overnight. Now all of her builds are broken, and she's really stuck.

- Even worse! There's a cat person out there that's trying to do harm, and they've hacked the origin server that holds some of the source code she depends on. All of a sudden, she's receiving the wrong code, and her packages are no longer working reliably. This malicious code that she got from a hacked origin might be really dangerous, and by the time she figures out what's happened, it might be too late!

There are few things she might consider here in order to protect herself and the people that depend on her code.

- Maybe she'll just stop having dependencies altogether. But that's really hard, because she would have to write a bunch of code from scratch, and she wouldn't be able to reproduce some of the APIs that she depends on, so the quality of her code would suffer.

- She could just vendor all of her dependencies, but that inflates the size of her repository, and she's worried that it will be difficult to maintain and update over time.

- Or, she might just decide to do nothing at all, and put her trust in the state of things as they are today. Trust that her dependencies won't disappear, and github and other code hosting sites will always give me and all the people that use her code what are asking for. But honestly, that's more trust that she's really comfortable with.

She has some options, but none of them solve all of the problems without creating new problems and risks of their own.

So let's explore some better solutions that popped up recently within Go.

- Modules can help us with our reproducible build problem

- Module Mirrors can help to eliminate the risk of disappearing dependencies

- A checksum database can help to eliminate the risk of getting the wrong code, making sure that every Go developer in the world gets the same code every single time.

Today, Katie intends to discuss these three things: modules, mirrors, and a checksum database.

Better Solutions: Modules

A module is a versioned set of Go packages that are related to one another in some meaningful way.

In her repository at github.com/katiehockman/puppies she has a few Go packages. Package walk, package bark, and package toys. These packages are all very related to one another, and share a lot of the same dependencies. She put each of these packages in a single module that can now be versioned.

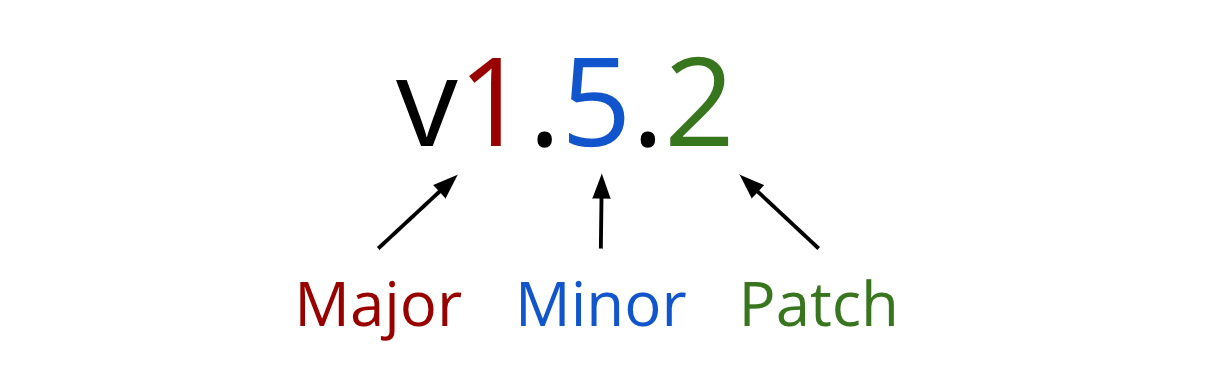

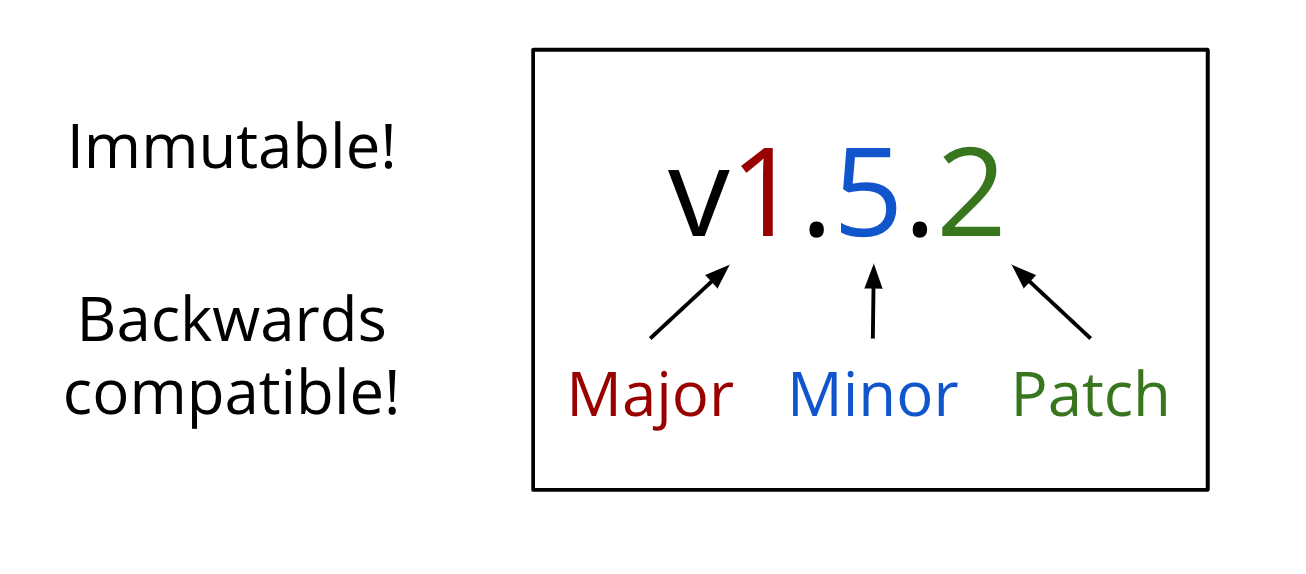

A module's version has a major, minor, and patch component to make up it's semantic version.

If you wanted to import a package before the existence of modules, you either had to vendor that source code if you wanted a specific commit, or you had to rely on the latest version of that package at the source.

Now, packages can sit inside of a module that's a versioned snapshot in time, to uniquely identify it for everyone. The contents of a version are never allowed to change.

Every new commit to this major version of the module also has to be backwards compatible.

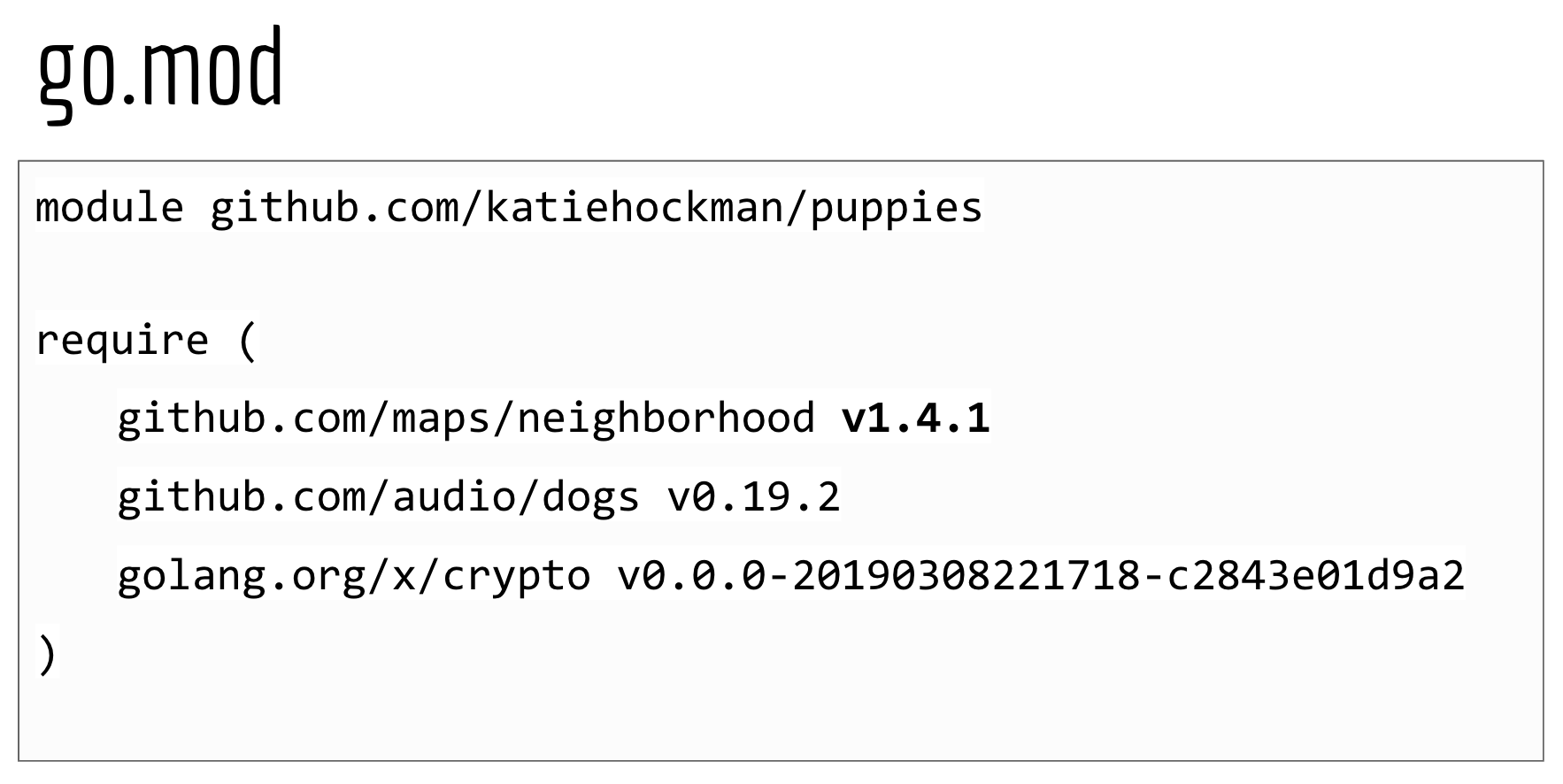

For something to be a module, it only needs a go.mod file that sits at its root directory.

A go.mod file looks something like this:

module github.com/katiehockman/puppies

require (

github.com/maps/neighborhood v1.4.1

github.com/audio/dogs v0.19.2

golang.org/x/crypto v0.0.0-20190308221718-c2843e01d9a2

)A go.mod file specifies the minimum version of all of the packages that your module uses. It is the only file you need to look at in order to figure out which direct dependencies a module has.

You could see semantic versions like v1.4.1 as well as pseudo-versions like v0.0.0 with a date and commit hash, which can be helpful if you either want to depend on a specific commit, or if the repository doesn't have version tags yet.

By specifying that your code relies on a module with version 1.4.1 or later, then you guarantee that everyone who imports your package will never be allowed to use a version older than 1.4.1 with your code.

The go command uses something called "minimal version selection" to build a module, based on the versions specified in a go.mod file.

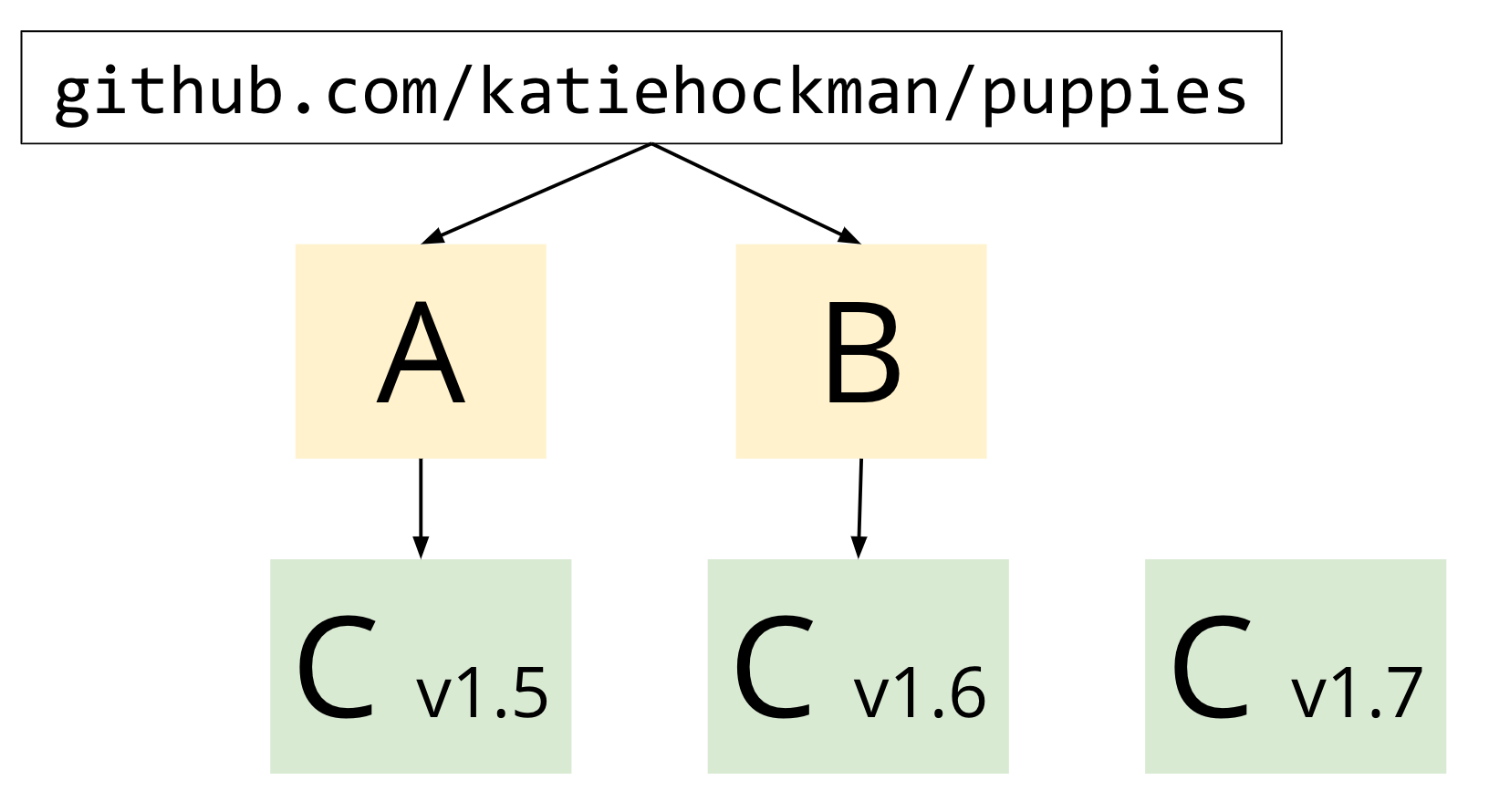

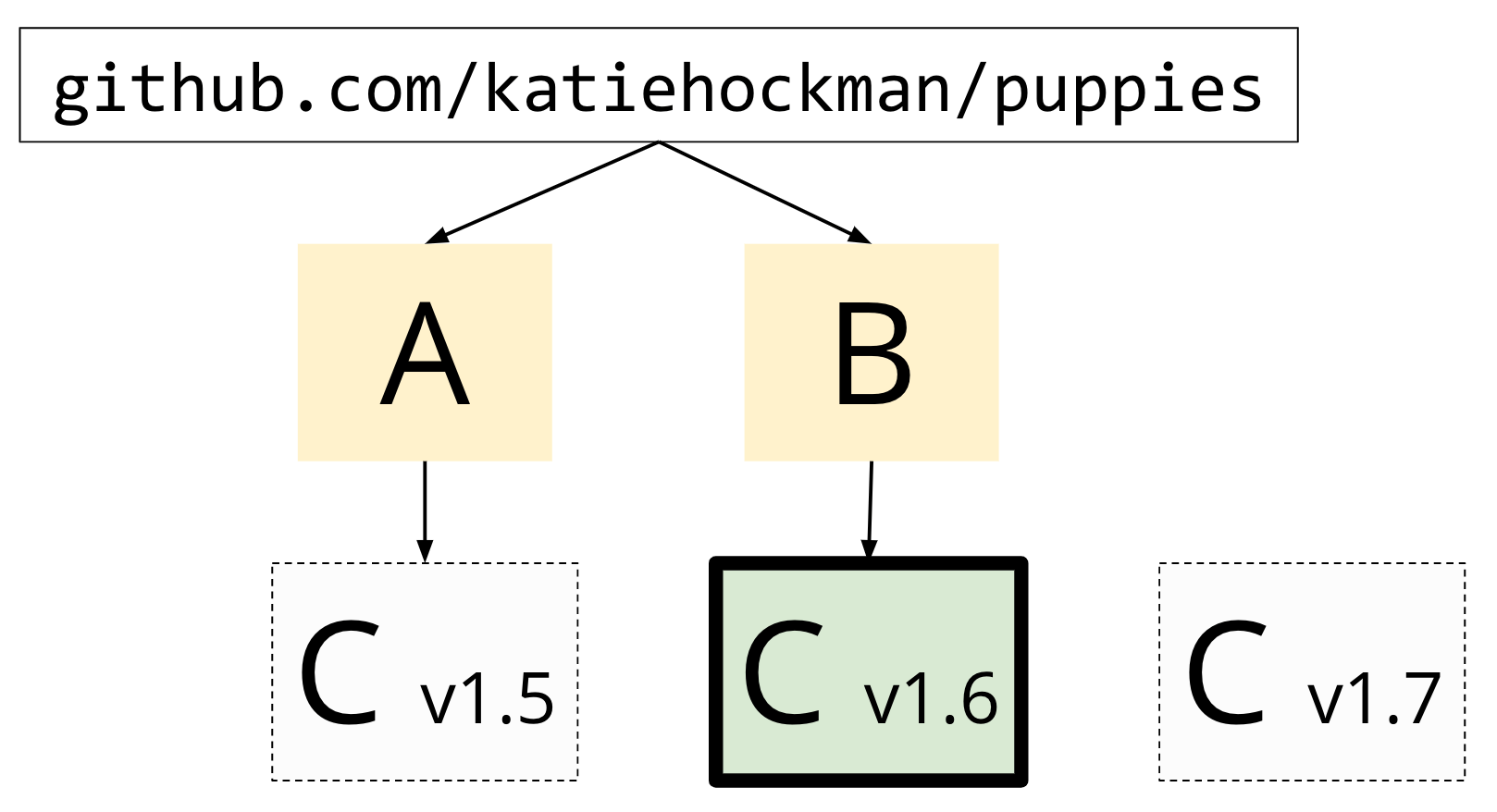

As a basic example, let's say we have module A and B, both of which Katie's module depends on.

Each of these modules relies on C, but at a different version. "A" requires at least version 1.5 and "B" requires at least version 1.6.

C has also published another, newer version. 1.7

If her module relies on A and B, then the go command will choose the minimum possible version that satisfies the constraints of A and B's go.mod files when doing a build. In this case, that would be version 1.6.

This minimal version selection guarantees reproducible builds because the go command uses the oldest allowed version of each dependency in the build, instead of the newest one which may change day to day.

Now we have consistent, reproducible builds that are no longer contingent on the latest commit history of a dependency.

One problem down, two to go. So, we've solved the problem of reproducible builds, next let's talk about how we can be sure that our dependencies won't disappear.

Better Solutions: Module Mirrors and Proxies

Now that we have a versioned module that is never allowed to change, we have new opportunities for caching and authentication that non-module mode didn't.

This is where module proxies come in.

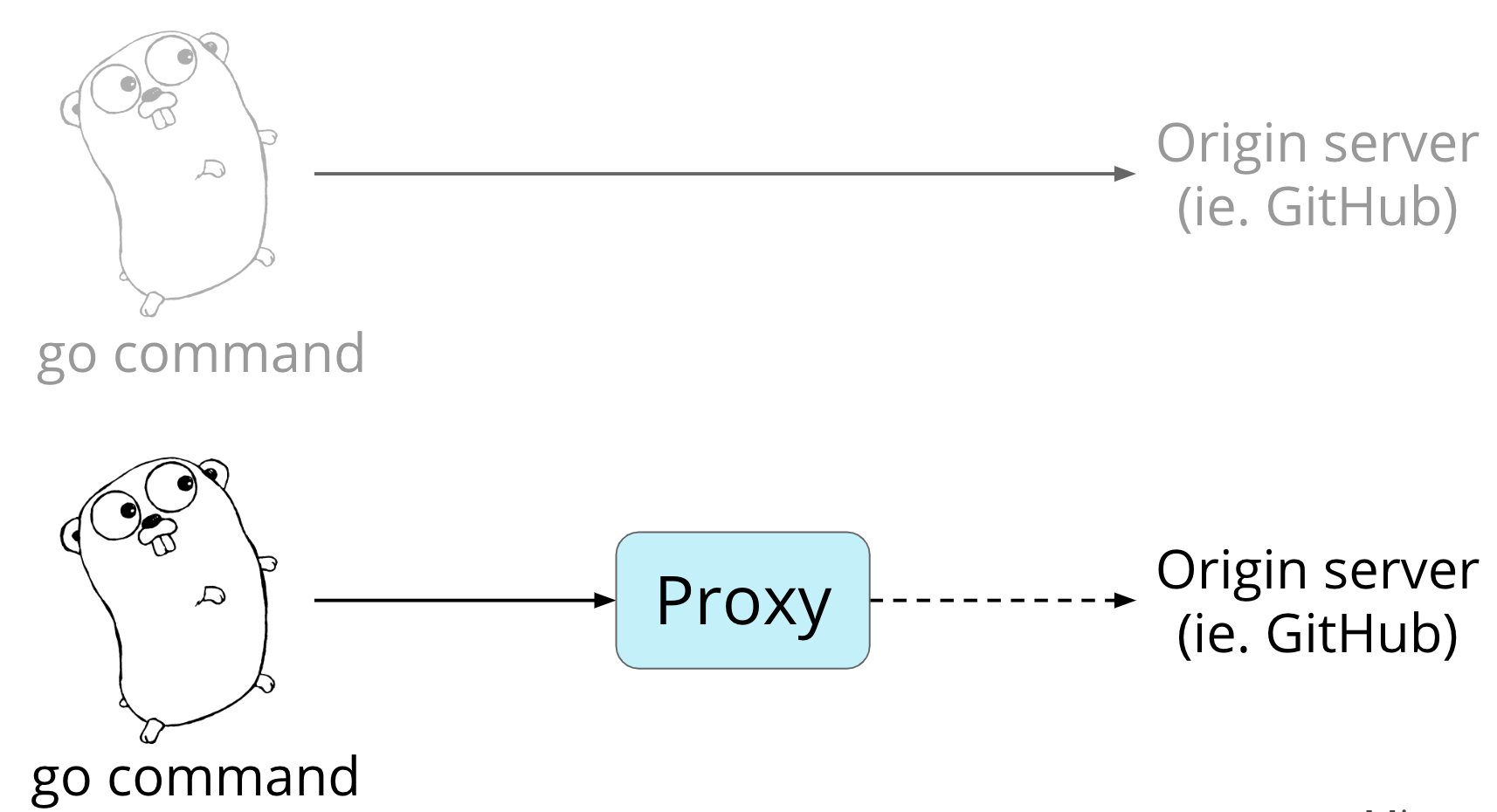

This is what the flow looks like without a proxy. Pretty simple, right?

A Go developer runs a go command, like go get. And the go command hits the origin server directly every time the package isn't in the user's local cache. By origin server here, we're referring to any place where Go source code is hosted. Like GitHub, for example.

'go get' changes behavior depending on whether the go command is running in module-aware mode or if its running in GOPATH mode. Proxies are only used in module-aware mode, so that's the behavior we're going to discuss.

go get has two major jobs we're going to discuss:

- to go out and get the code that you asked for

- to understand the new dependencies for your module based on the code it just fetched. It has to resolve those dependencies, and may need to update your go.mod file.

But without a proxy, this can become really expensive, really quickly. Both for latency, and for storage on your system.

The go command may be forced to pull down the entire source of a transitive dependency, even if it isn't building it right now, just to make a consistent decision about dependency versions during its resolution.

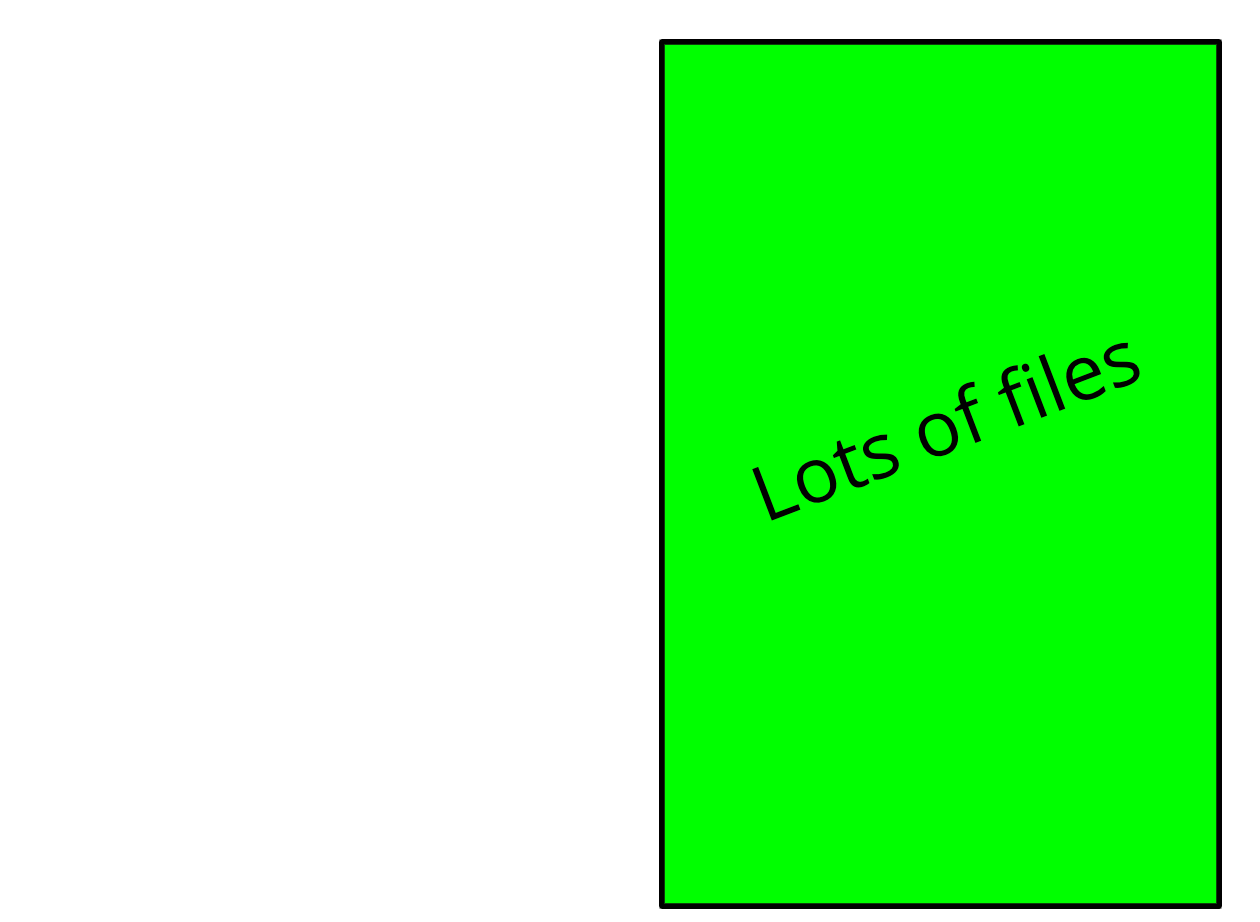

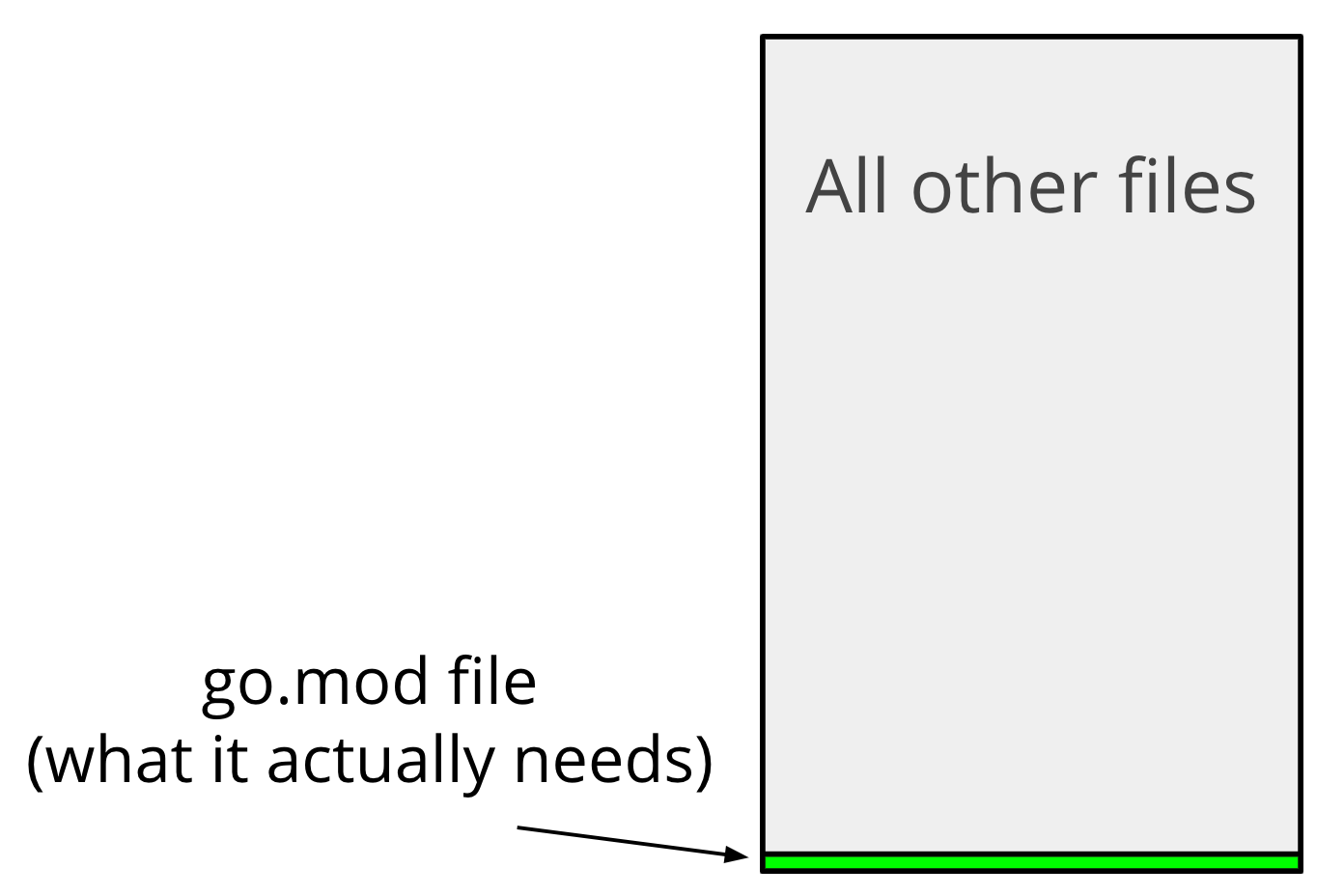

So for the dependency resolution, this is what the go command is fetching

And this is how much of that source that it actually needs.

Remember that the only thing the go command needs to understand the dependencies of a module is a single go.mod file. So, for 20 MB modules, it only needs a few KB go.mod to do this dependency resolution. That's a lot of storage in your system's cache that is going unused, and it's a lot of wasted time connecting to the origin and pulling down a large file like this when it doesn't really need to.

For those of you that have been using modules without a proxy for some time, this is the reason behind some of the latency you've seen, and this is where a module proxy comes in.

Going back to our example with the go command fetching source code, let's put a module proxy into the picture.

If you tell the go command to use a proxy, rather than reaching out to the origin server directly like before, it will instead hit the proxy to ask for the thing it wants.

Now, instead of interacting with an origin server, the go command can interact with a proxy that has an API better suited for its needs.

Let's walk through what this interaction with a proxy looks like.

She's working on her puppies module, and she's decided that she wants to import a new package that tells me information about the different dog breeds.

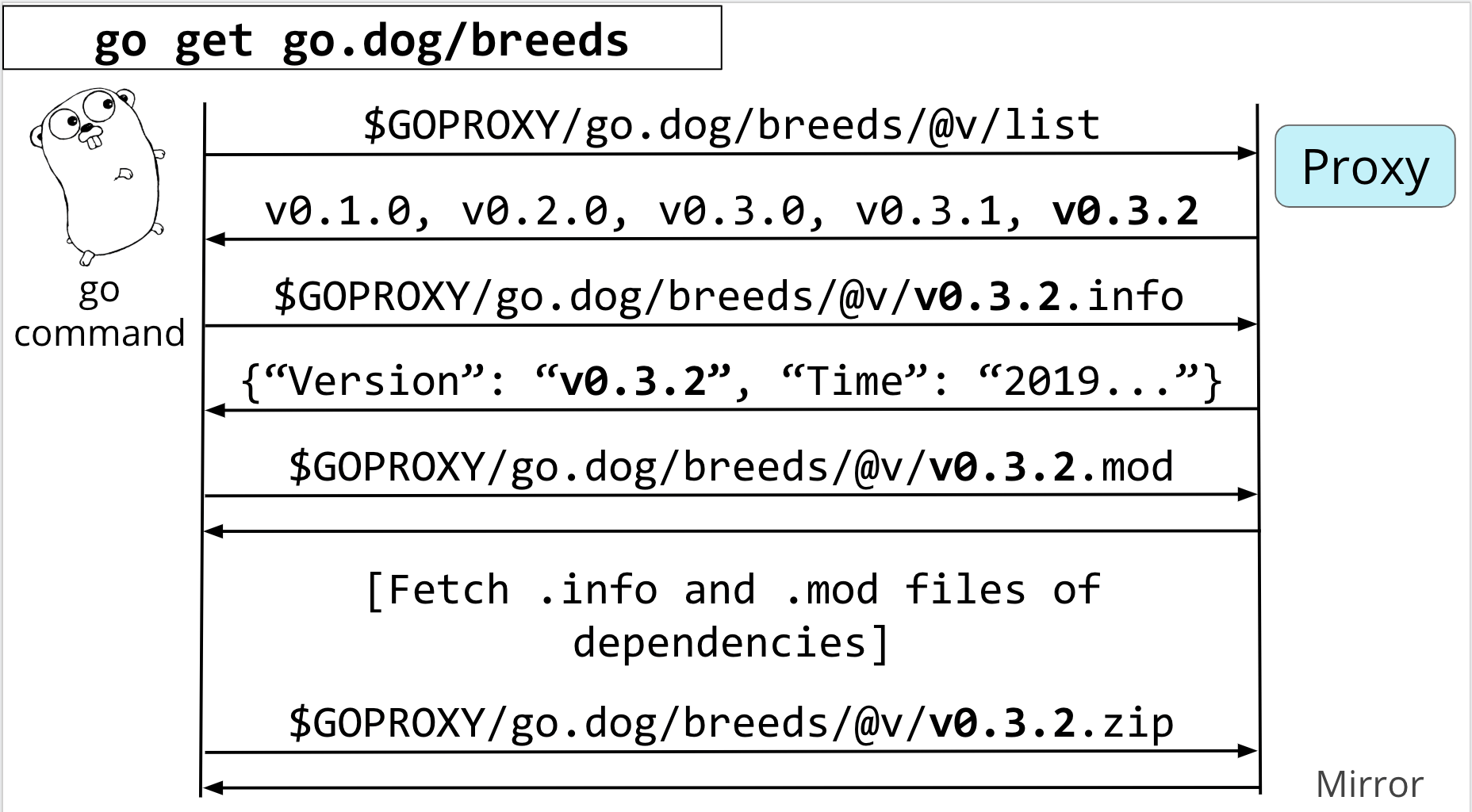

The first thing she'll do is run go get go.dog/breeds

The proxy is going to give back a list of versions that looks something like this, with tagged versions like 0.1.0 and 0.3.0. The go command was looking for the latest tagged version, and in this case, it's v0.3.2

Now, the go command knows the latest tagged version, it is going to hit an /info endpoint on the proxy for version 0.3.2 of go.dog/breeds. This info endpoint is going to give some extra metadata about that tag.

This metadata includes the canonical version for this tag or branch, as well as its commit timestamp.

It's going to use this canonical version given back by the proxy going forward.

Now it's time for the go command to start understanding and resolving the dependencies of go.dog/breeds at v0.3.2. It'll do this by asking for the go.mod file.

The go command is going to repeat the previous two steps of requesting the .info and .mod files of each of the transitive dependencies, walking down the tree to resolve one dependency at a time.

Now that it's dependency resolution is done, it has to actually get the source code that you originally asked for, so it's going to do that next with one more request for the.zip file from the proxy that contains the source.

The really interesting thing here is this ability to fetch information about a module's transitive dependencies from a proxy, without requiring the entire zip of the source to do this.

The go command is able to just ask for the pieces of information that it needs to do its dependency resolution based on minimal version selection, and never have to look at the rest.

At this point, there is one part of this flow that you might be wondering about. What's that .info file doing, and why does the go command need it? In this example, we're asking for the info at version 0.3.2, and it's just returning back the same canonical version that we provided.

Let's see an example where that isn't the case.

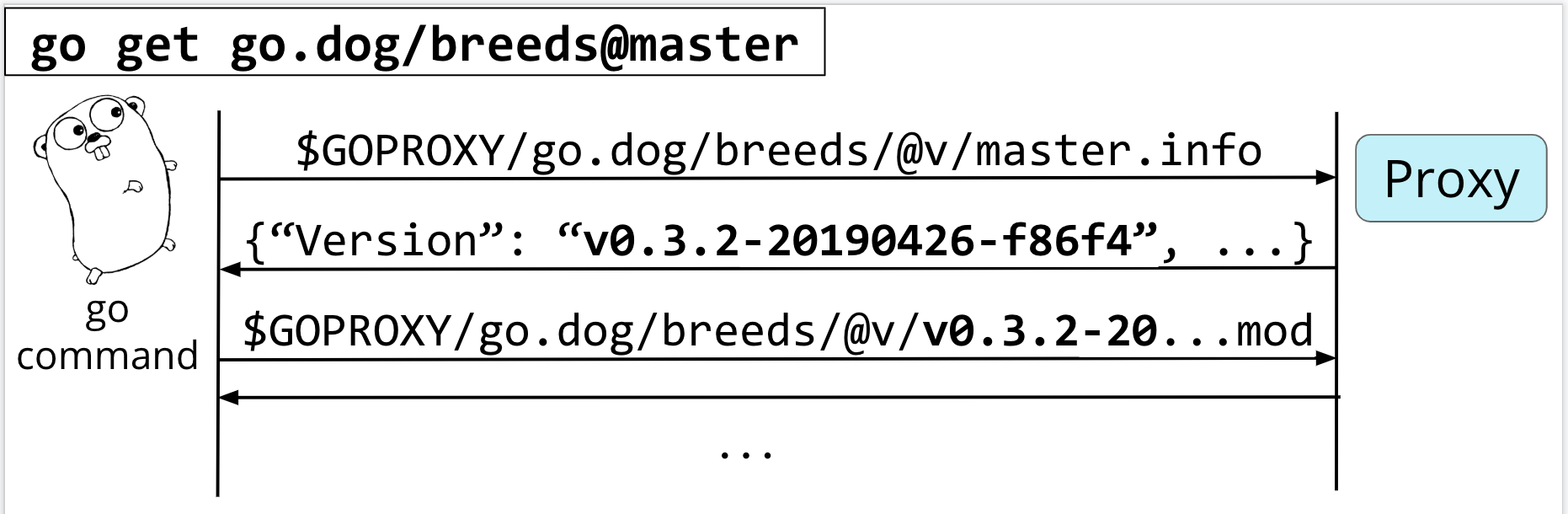

Let's instead run go get go.dog/breeds but append @master to the end. This is telling the go command that we want it to explicitly fetch what's currently at master, so we can skip hitting the list endpoint entirely.

We'll immediately jump into requesting the info for the master branch

In this case, you'll see that the info given back is a bit different. This time, we got a pseudo-version which is the canonical version at "master" at the time of the request.

Once it gets this canonical version back, it can proceed as before, pulling down and resolving dependencies, and requesting the zip file for the contents at the end.

I've been speaking about a proxy in general terms, because there is no single proxy out there. Any server that implements the module proxy specification can be used by the go command. This specification is given by running go help goproxy.

You can see the spec here, it has the /list endpoint for getting the versions, the .info endpoint for the JSON metadata, the .mod file for the dependency resolution, and the .zip endpoint for the full source code.

I started this section off by saying that module mirrors will solve our problems, but then she started talking about proxies instead.

Well, a mirror is just a special type of proxy that caches metadata and source code in its own storage system to re-serve to clients.

Mirrors can help you in more ways than one.

Mirrors can help solve our initial concern of code disappearing from the source.

They cache source code in their own storage system, so the risk of a developers pulling down their code from github no longer applies to you. If it suddenly becomes unavailable at the source because the server is down or having issues, then you have a mirror that should have a copy of that source code for you to salvage.

You'll likely see faster downloads

And less storage use on your system because the go command can ask only for what it needs, and not worry about the rest.

And fortunately, it should be super easy to use a proxy. You shouldn't need to install anything to use it. You don't even have to have git or mercurial installed because the proxy is doing that work for you.

All your system needs to do is be able to make HTTP requests to it.

Now we have builds that are reproducible, and we have more confidence that our dependencies won't disappear.

Let's talk about how we can trust the source code that the go command is fetching for you.

Without modules or proxies, the go command would fetch source code directly from the origin servers using HTTPS at head.

You could be reasonably confident that this was giving you the contents you wanted, but it was still possible that the origin server got hacked, and that was undetectable by the go command.

And since your code was relying on the latest commit, it did nothing to protect you from a package owner suddenly changing their source code out from under you.

With the introduction of modules, we also got something called a go.sum file.

You've probably seen this when you're using modules, and maybe scratched your head wondering exactly what purpose it's serving and what (if anything) you are supposed to do with it.

This go.sum file is meant to act as your record for what source code looked like when you downloaded it, the first time the go command saw it from your machine. The go command can use them in some situations to detect misbehavior by origin servers or proxies that might be giving you different code than you saw earlier.

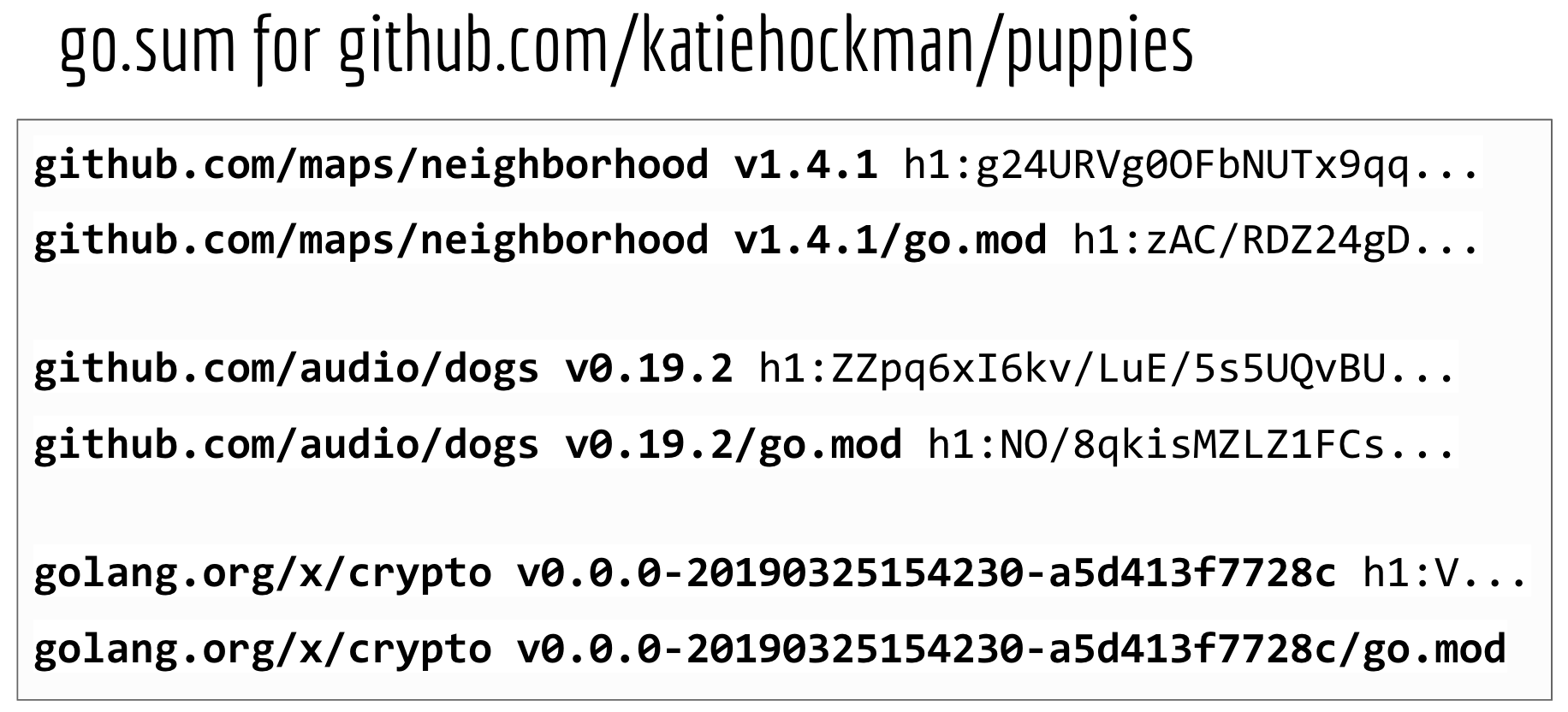

So here's that somewhat confusing looking go.sum file she was talking about, which sits right next to your go.mod file in the root directory of your module.

It's basically a list of SHA-256 hashes of your dependencies and their go.mod files. Because this is a cryptographic hash, it is essentially impossible to make any changes to the files in a particular version without affecting the hash.

You should never really have to touch this file, it is something generated by, updated by, and used by the go command. But understanding how it is used is important in understanding its limitations.

And by the way, if you look at a go.sum file in the wild, it's likely to be much longer than this one. It'll also include a bunch of modules that probably don't appear in your go.mod file. That's just because it also includes the go.sum lines of everything the go command has fetched for this module, including any transitive dependencies as well, even if they don't appear in your go.mod file anymore.

The go command can use these checksums for one very cool thing in particular: for detecting whether or not the code that you are trying to download now is different than it was a month ago when you last saw it.

This go.sum file should be checked into your repository, because the go command can use this as a source of trust going forward when anyone tries to download your dependencies.

Once it's checked into your repository, the go command will check against your module's go.sum file when it fetches code.

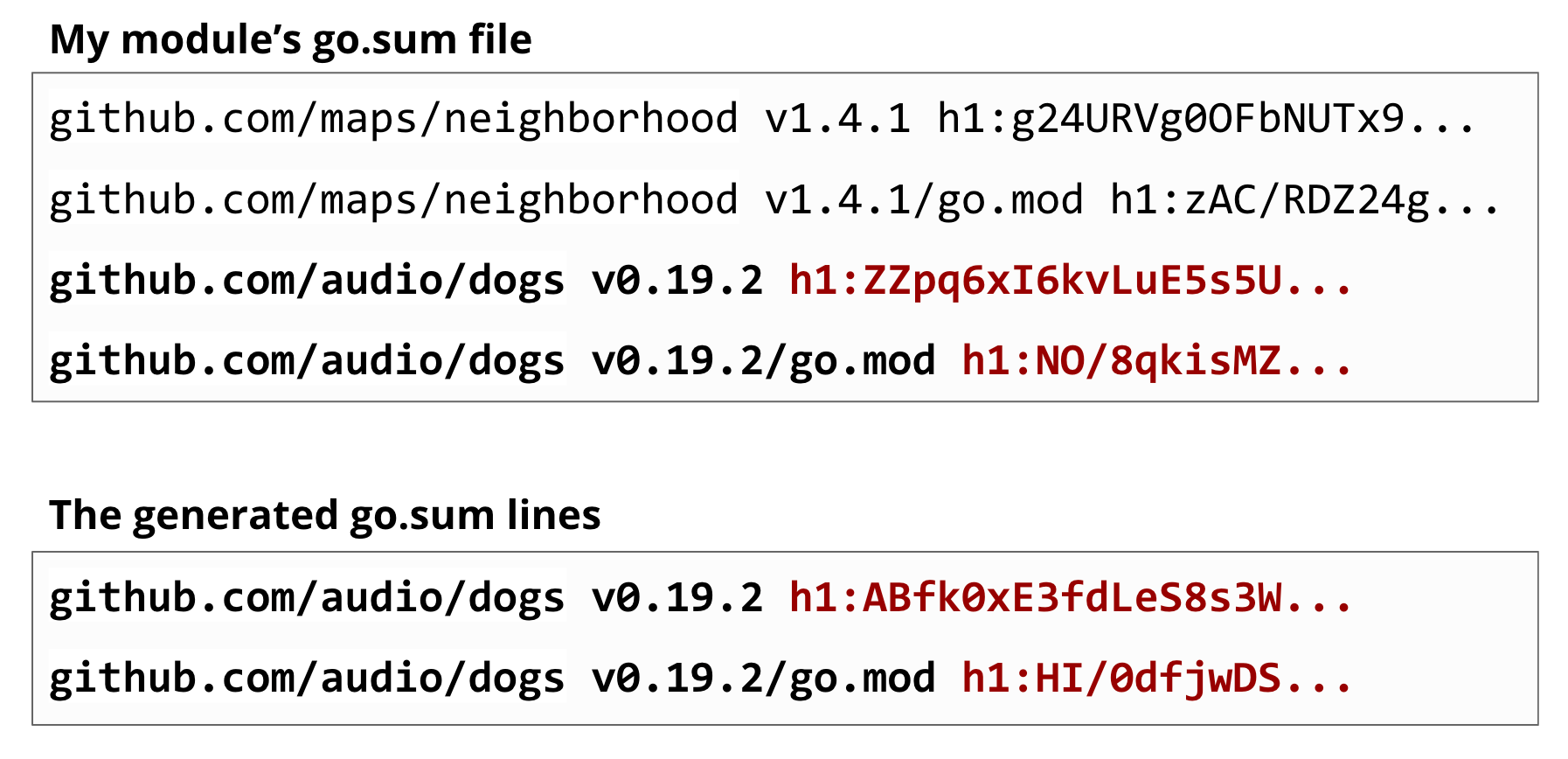

Let's say we cleared out our module cache and need to re-fetch our module's dependencies again. It's going to fetch the dependency's mod and zip files, do the hashes, and may see that the go.sum lines that it just generated don't match the ones that you had saved in your previous go.sum file.

This might mean that this source code was modified, a proxy or origin server has been hacked, or a herriad of things. All we know is that it's different than what we trusted before, and we shouldn't use this.

All of this is a definite improvement from having no go.sum at all, but it has its limits.

The downside: it works by "trust on first use", and more specifically, your first use.

When you add a new dependency to your module that you've never seen before, including when you upgrade to a new version of a dependency you are already using, the go command fetches the code and creates the go.sum lines on the fly. It doesn't have anything to check it against, so it'll just pop them into your go.sum file.

The problem is, those go.sum lines aren't being cross checked against anyone else's. You are just accepting that whatever code you just downloaded is the right code, and your go.sum file will be your source of truth for that dependency for now on.

This means that your module's go.sum lines might be different than the go.sum lines that the go command just generated for someone else, perhaps because you requested them a week apart and the code has changed, or perhaps because someone was targeting you to give you malicious code. So not a perfect, complete solution to our problem.

To add some extra risk for receiving the wrong code, you may have realized something really important when she started talking about proxies.

Who's to say that a proxy is actually giving you the code that you asked for? What kind of confidence can you have that a proxy isn't intentionally targeting you, and serving you something different than everyone else to do you harm? If you didn't check in your go.sum file, what happens if the proxy serves you something different when you ask for the same source code a month from now?

All of a sudden, our relatively secure direct endpoint has been replaced by a proxy that has every ability to lie to us, and isn't really trustworthy on its own.

In the best possible scenario, we can imagine a world where the code author tells us what the go.sum lines should be, and we can always validate against that. But with Go code living in so many different origins like GitHub and Bitbucket, there is no single place to host code, and that's a great part of the go ecosystem that we don't want to change.

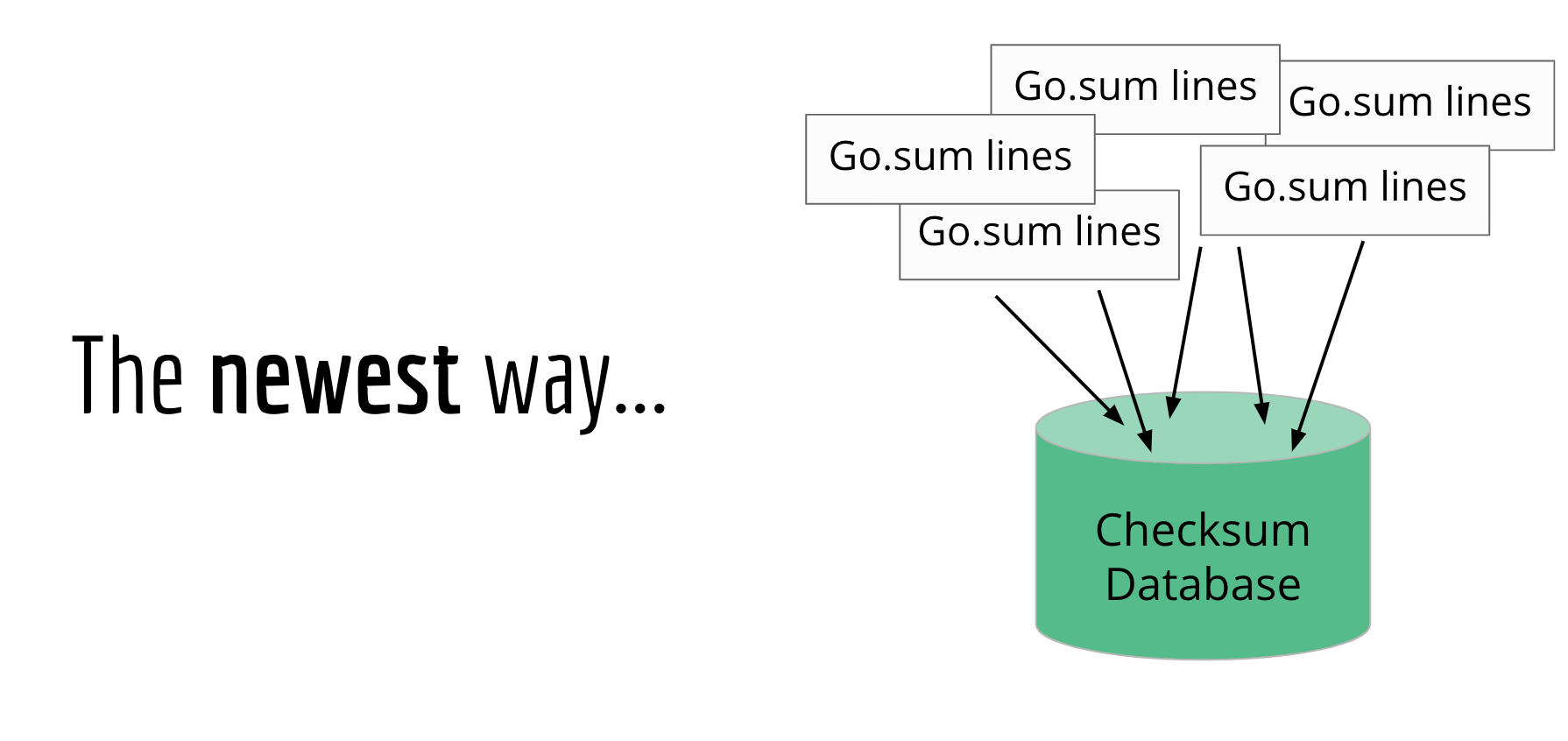

What we can do instead is the next best thing: let's make sure that everyone agrees to add the same go.sum lines to their module's go.sum file.

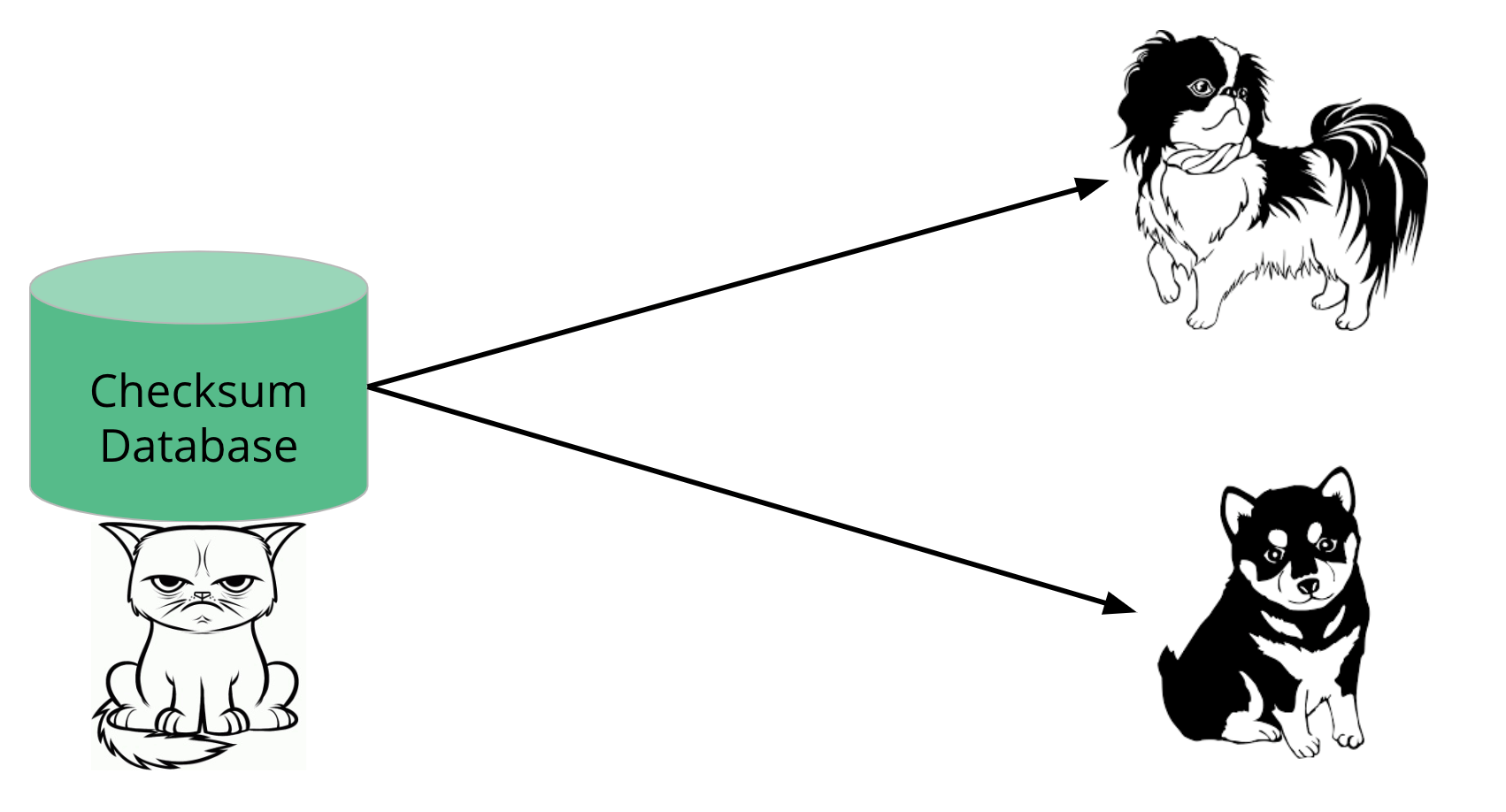

We can do this by creating a global source of go.sum lines, called a checksum database.

Once the go command gets its code from a proxy, it can then verify those contents against this global checksum database, to make sure the hashes match.

You can imagine a simple way of doing this.

We could just have a database running on a server somewhere that can give you the go.sum file upon request. We can tell the community that we'll behave, and ask that they trust us to do the right thing.

But, all that really does is take a problem

And move it somewhere else. All we would be doing is creating a different target for attackers to focus on.

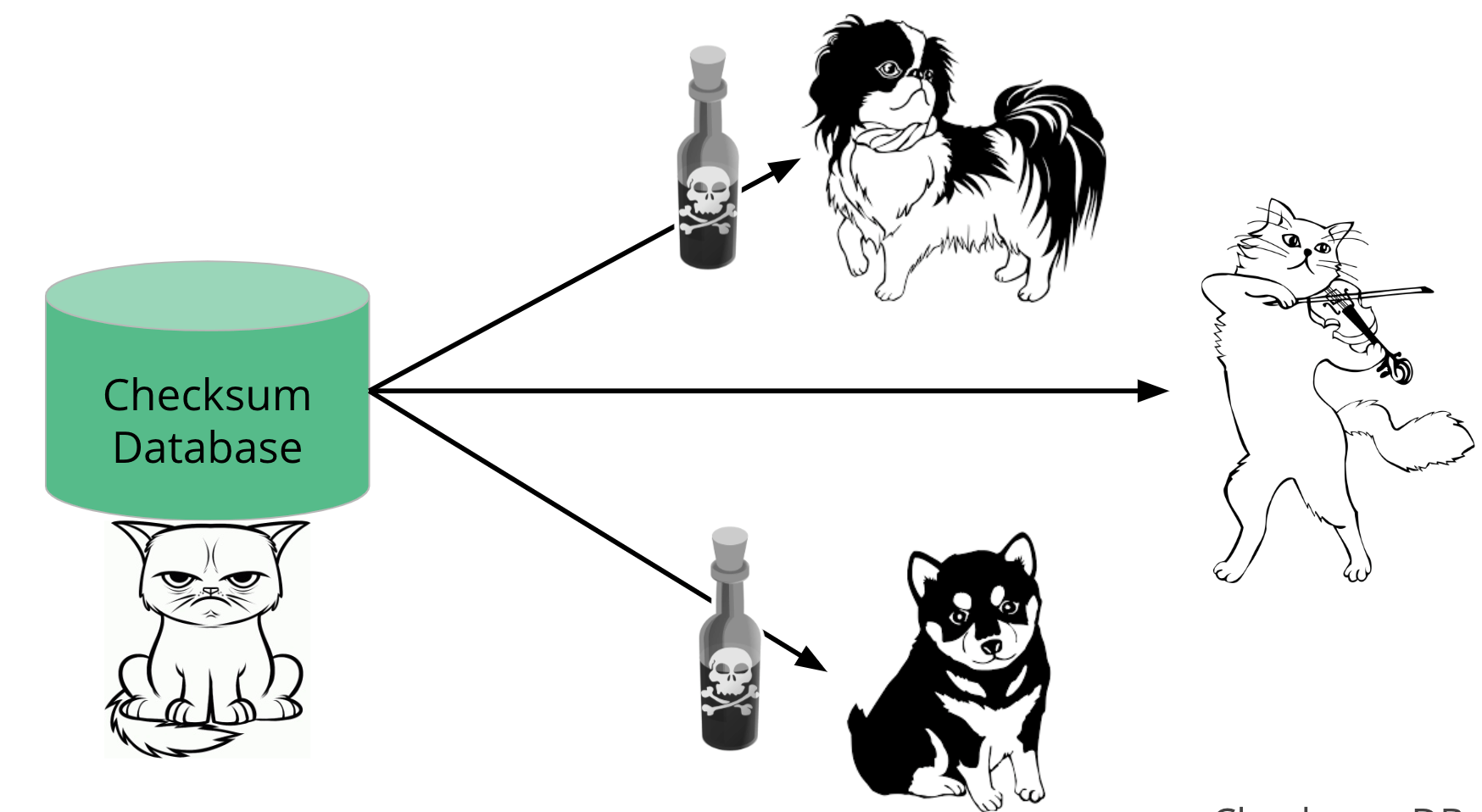

You can also imagine a scenario where the checksum database is run by those cat people she was worried about before.

With a simple database, it would be easy for the checksum database to start targeting the dog people.

They could serve checksums for the real code to all the cat people, but serve checksums for a malicious version of that code to the dog people.

Auditing an entire database is difficult and expensive.

It's also easy for man-in-the-middle attacks to go undetected, and manipulated data to go unnoticed by clients.

We shouldn't have to trust the checksum database as a source of truth without any means of holding it accountable.

We need a solution that won't let the checksum database misbehave, and will make targeted attacks easily detectable to auditors and the go command.

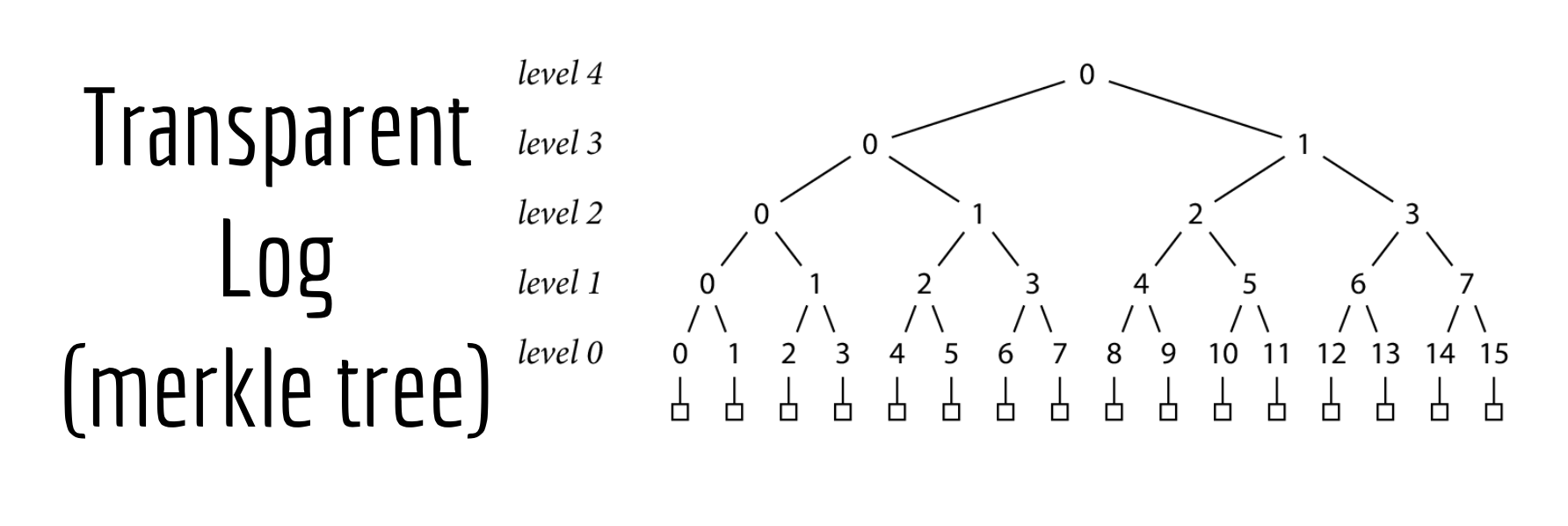

Transparent Logs and Merkle Trees Research

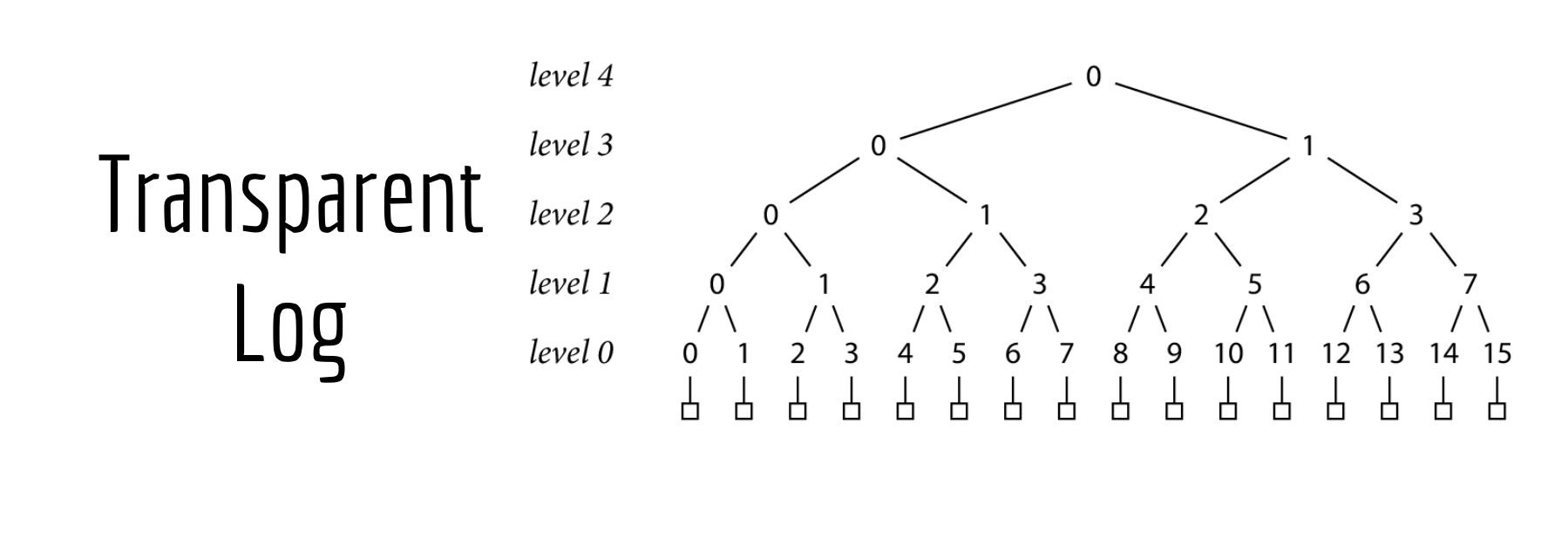

We'll do this by storing our go.sum lines inside what's called a Transparent Log. It's a tree structure that's built by hashing node pairs.

This is the same technique used by certificate transparency to protect HTTPS.

You may have also heard this called a merkle tree, if you've been spending too much time with crypto folks.

We use this merkle tree, instead of a simple database as our source of truth, because merkle trees are much more trustworthy. Its main advantage is that it's tamper proof.

It has properties that don't allow for misbehavior to go undetected.

Once you put a record in the log, it can never be modified or deleted.

If a single record in the log is changed, then the hashes would no longer line up, and it would be immediately detectable.

So if the go command can prove that the go.sum lines that it's about to add to your module's go.sum file is in this transparent log, then it can be very confident that these are the right go.sum lines to add to your module's go.sum file.

Remember that our goal is to make sure that everyone is getting the "correct" module version from a proxy or origin server every time.

And from our and the go command's perspective, "correct" means..

"the same as it was yesterday and every day before that, for every single person that asks for it", so it's important that we have a data structure that can't be tampered with.

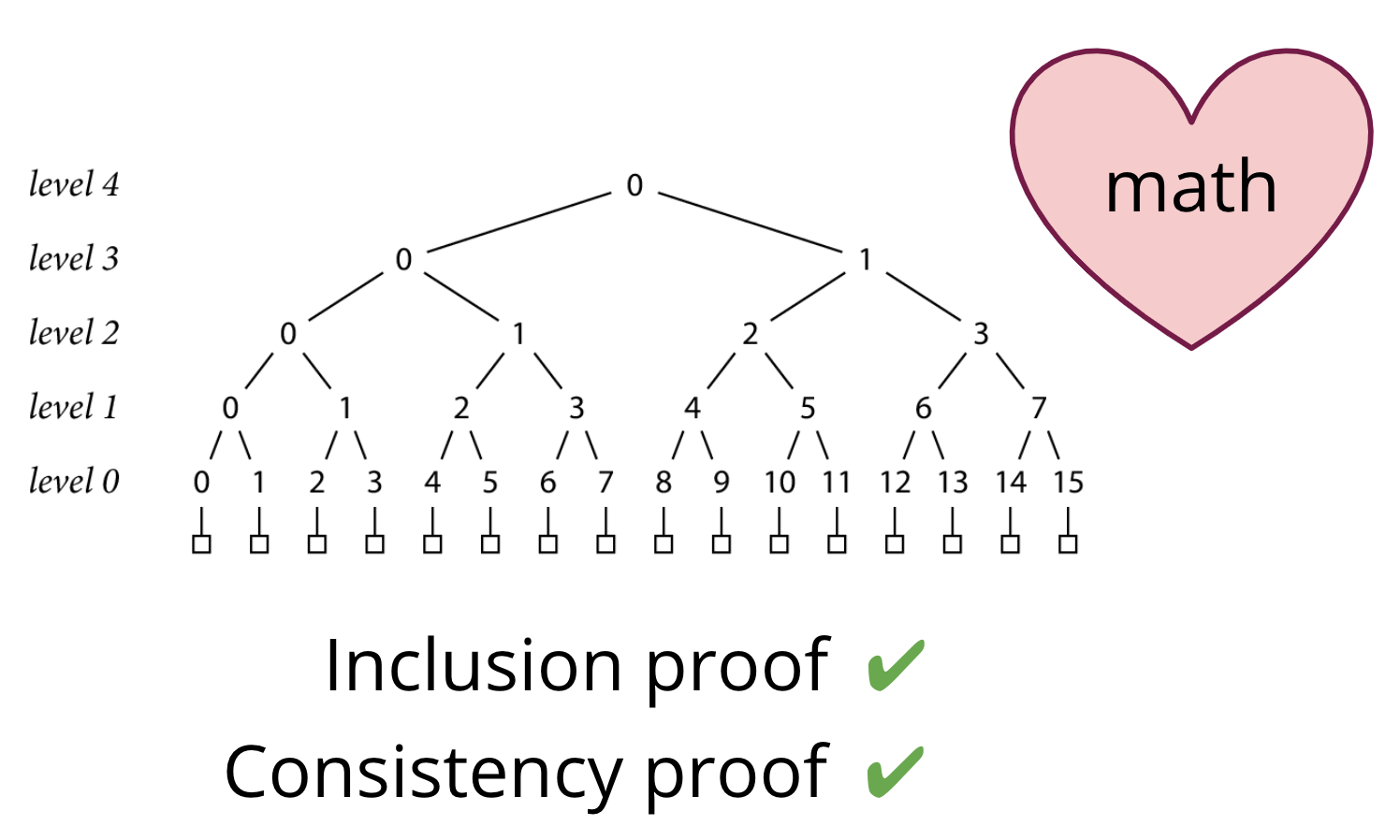

This log provides a very reliable way to prove two key things to auditors and the go command:

- That a specific record exists in the log through something called an "inclusion proof".

- That the tree hasn't been tampered with. Specifically, that a later tree contains an older tree that we already knew about, called a "consistency proof".

These two proofs can give the go command confidence when validating against a set of go.sum lines in this log. The go command performs these proofs on the fly before adding new go.sum lines to your module's go.sum file.

We hope the community will run a few external auditors, since those auditors are crucial for this system to work. They should work together to watch and gossip about the state of the tree as it grows, to alert on any suspicious behavior.

I won't go into all of the cryptography in this presentation, but let's just talk about a little bit to give you an idea of how this works. And hey, who doesn't love a little math :)

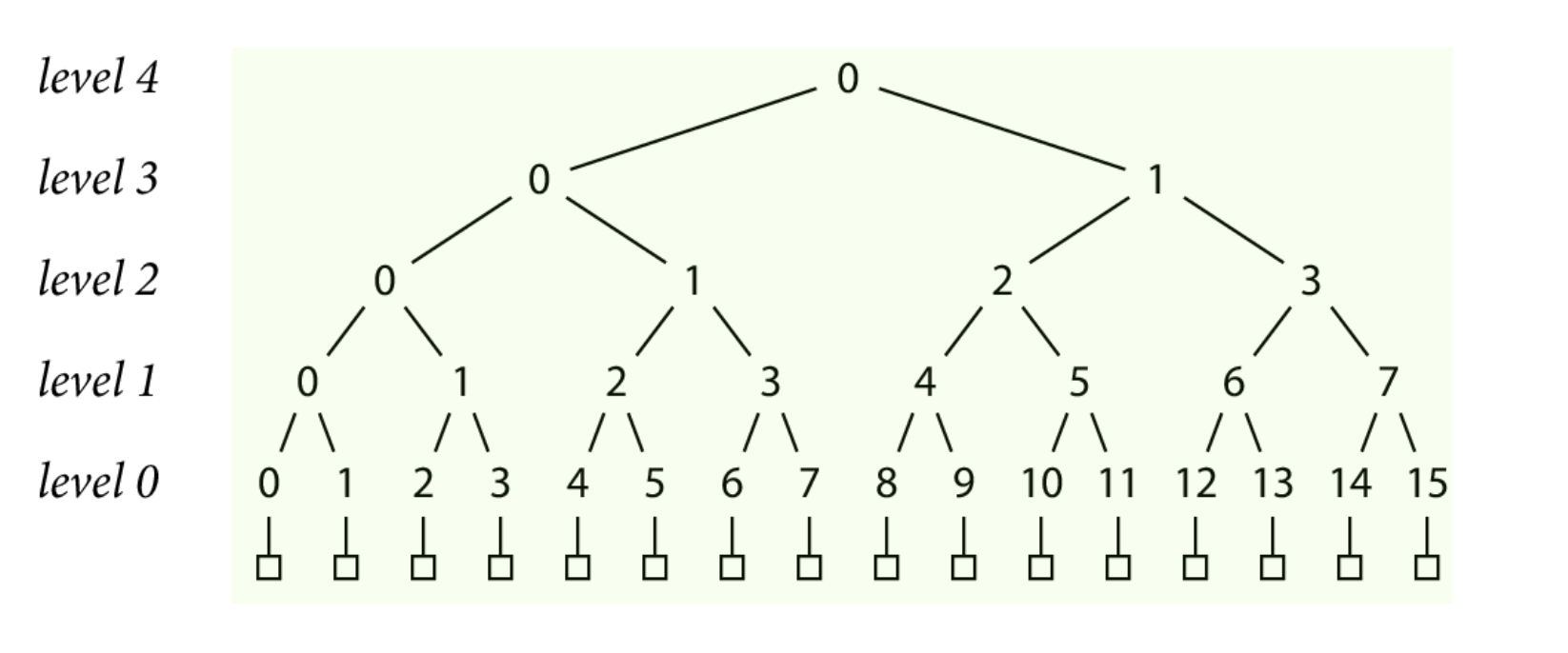

So let's jump into an inclusion proof

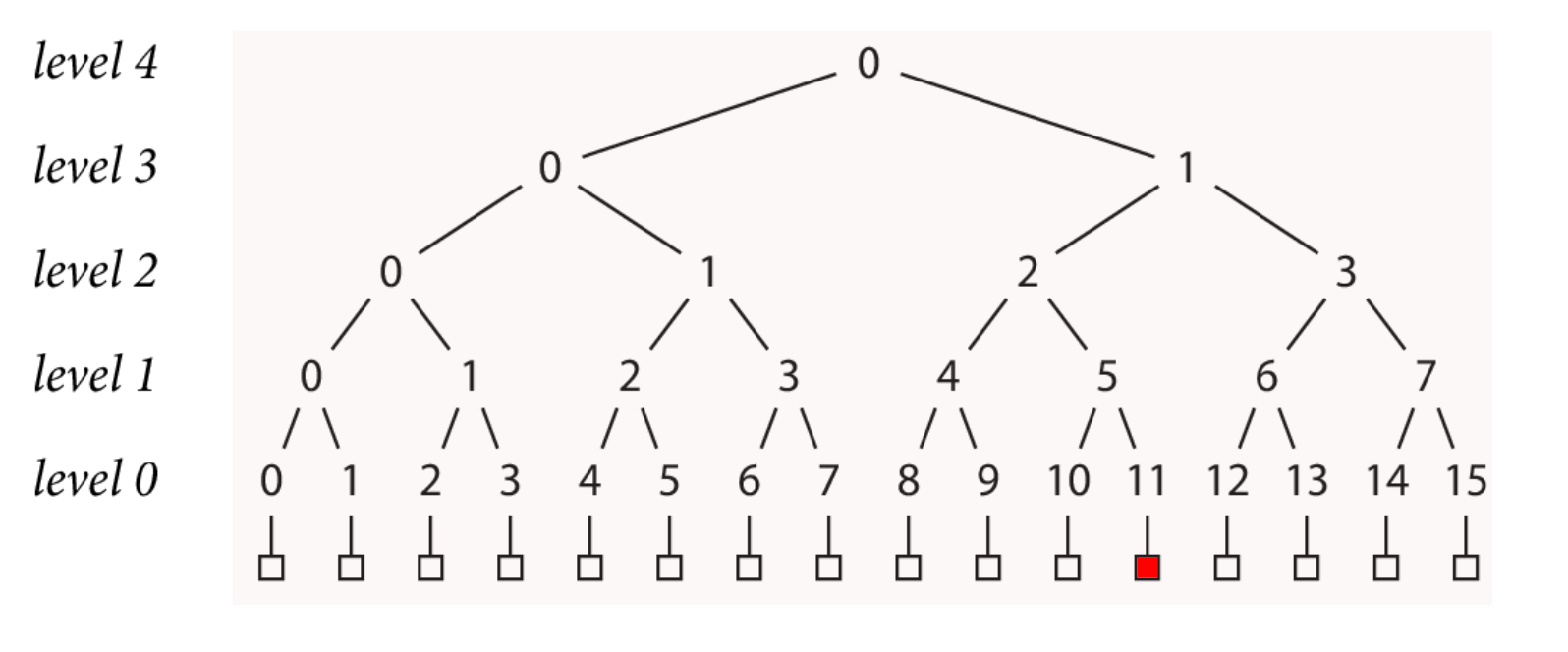

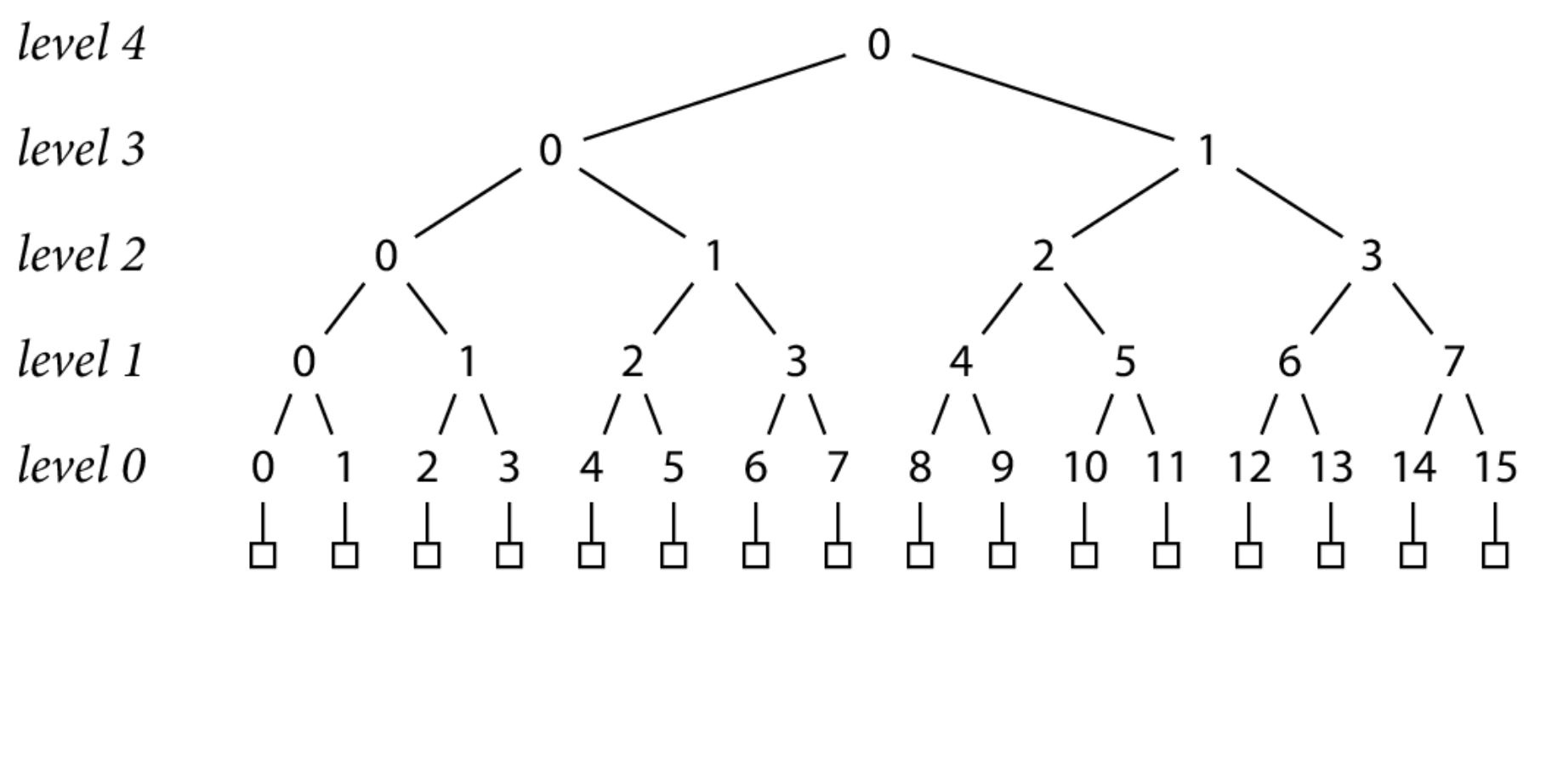

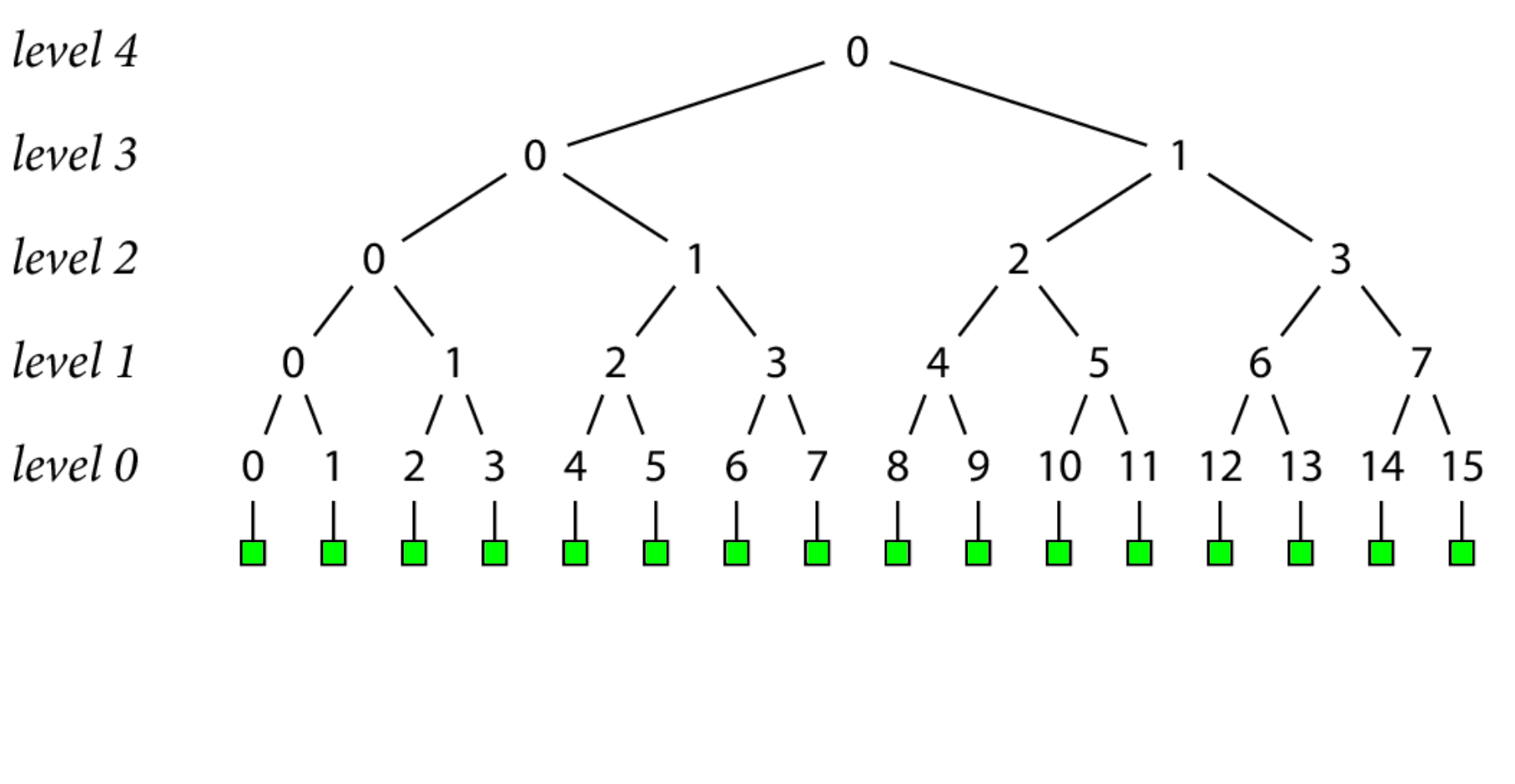

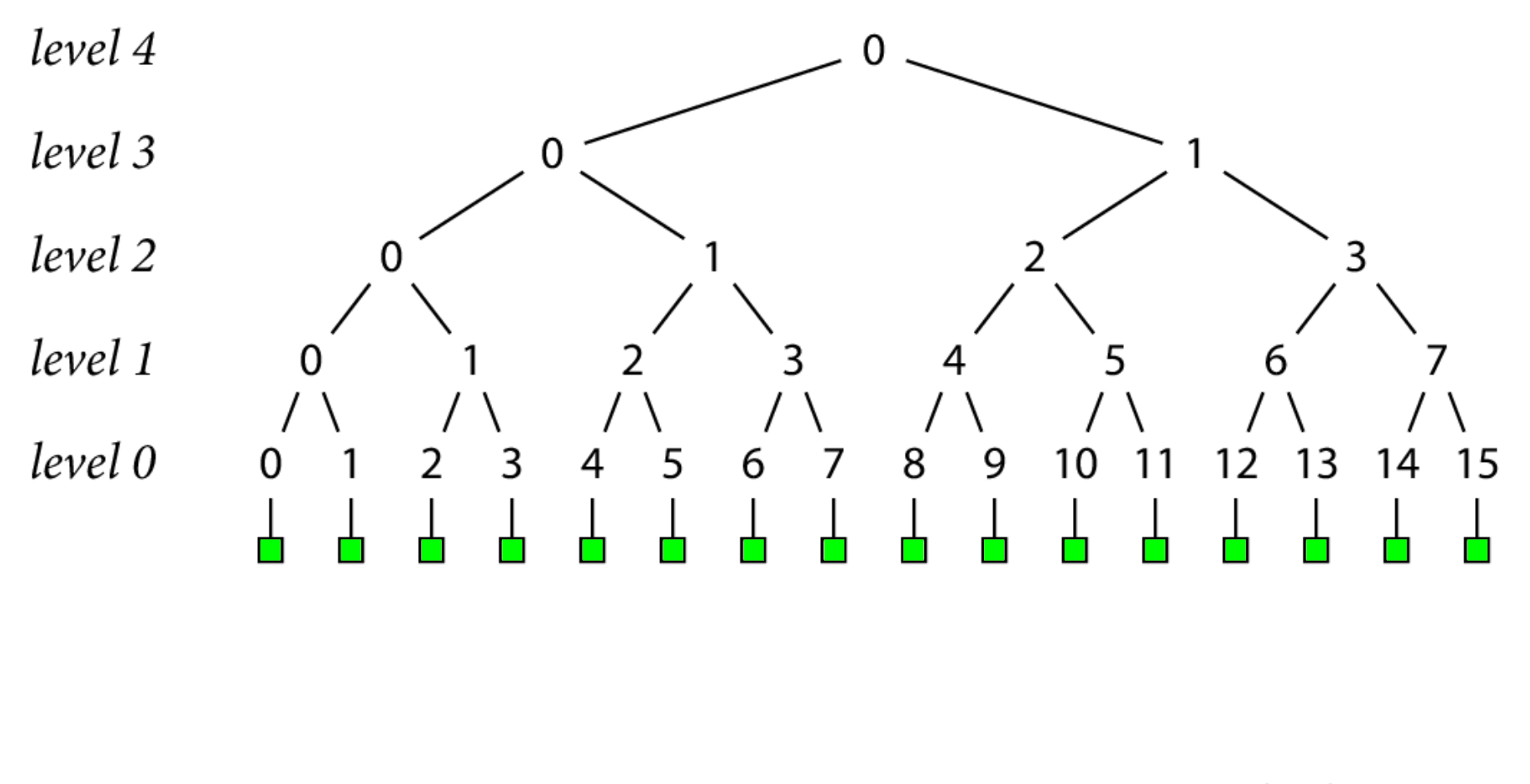

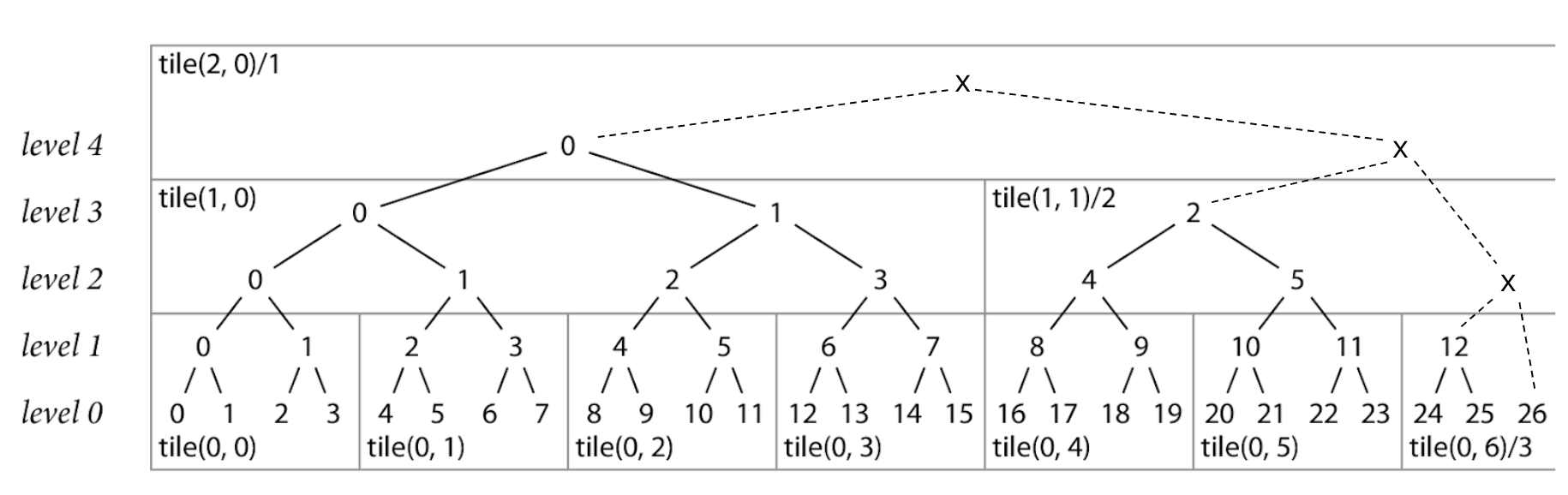

Let's start with what this data structure actually is, and how its built.

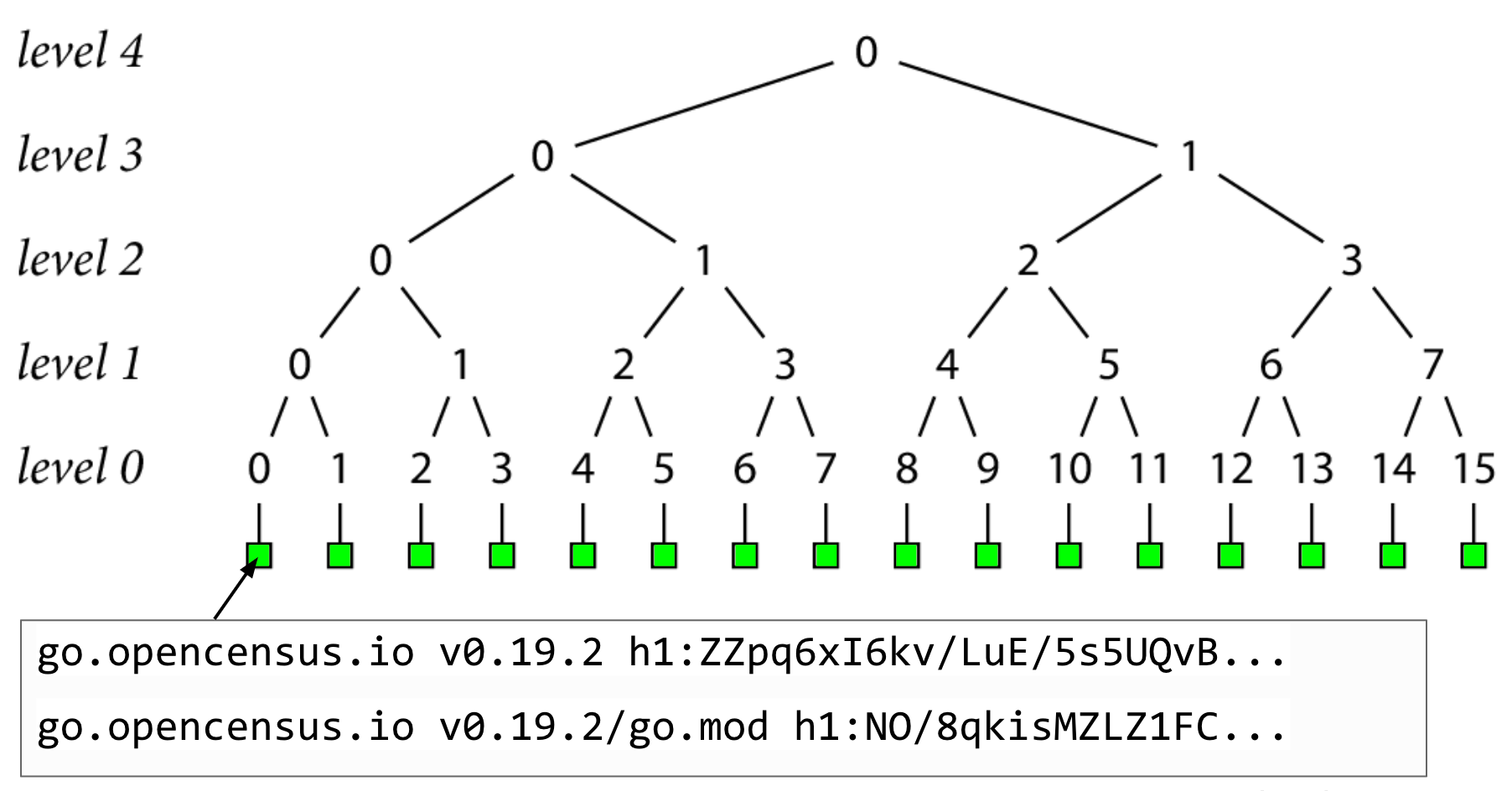

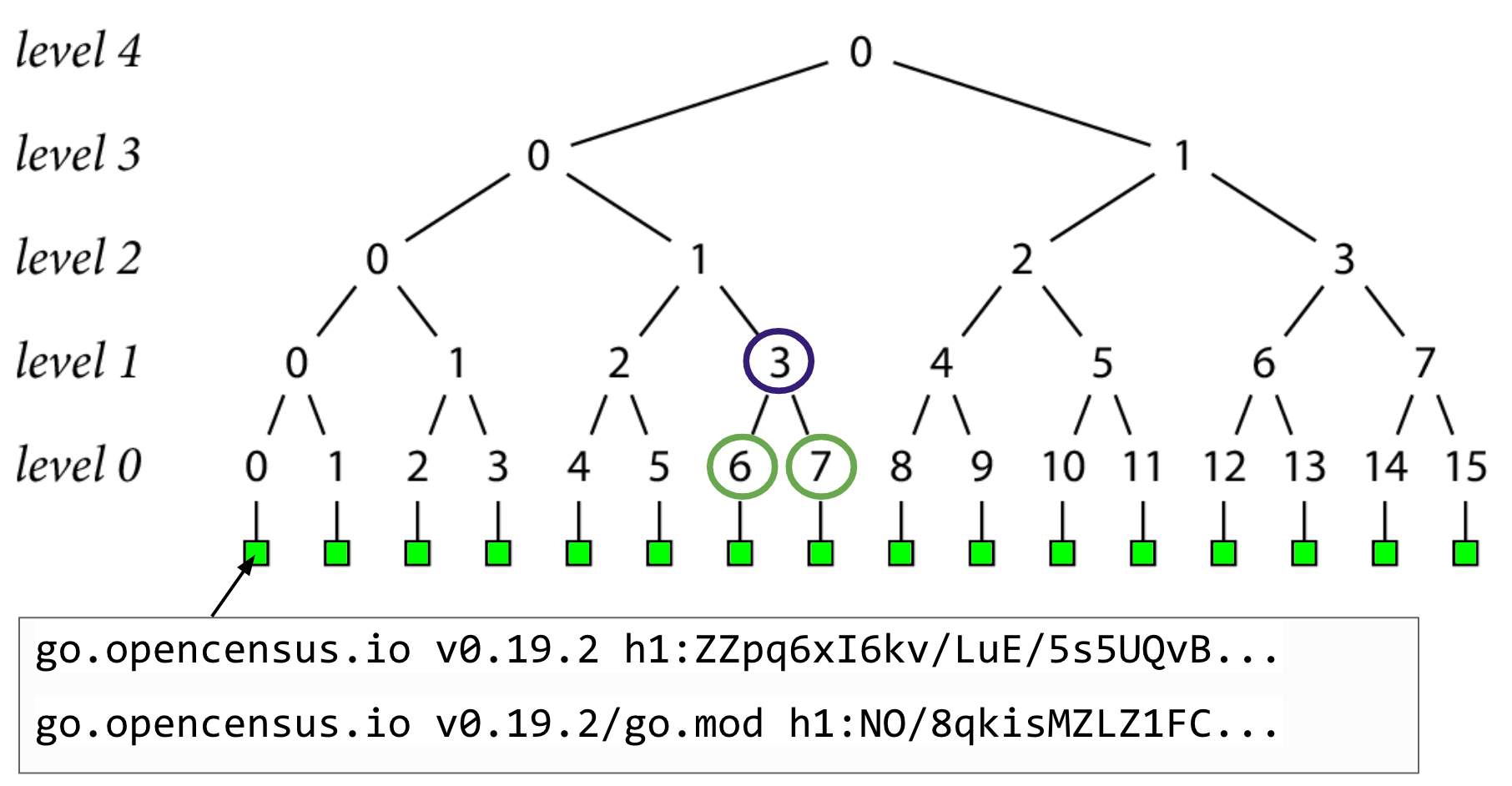

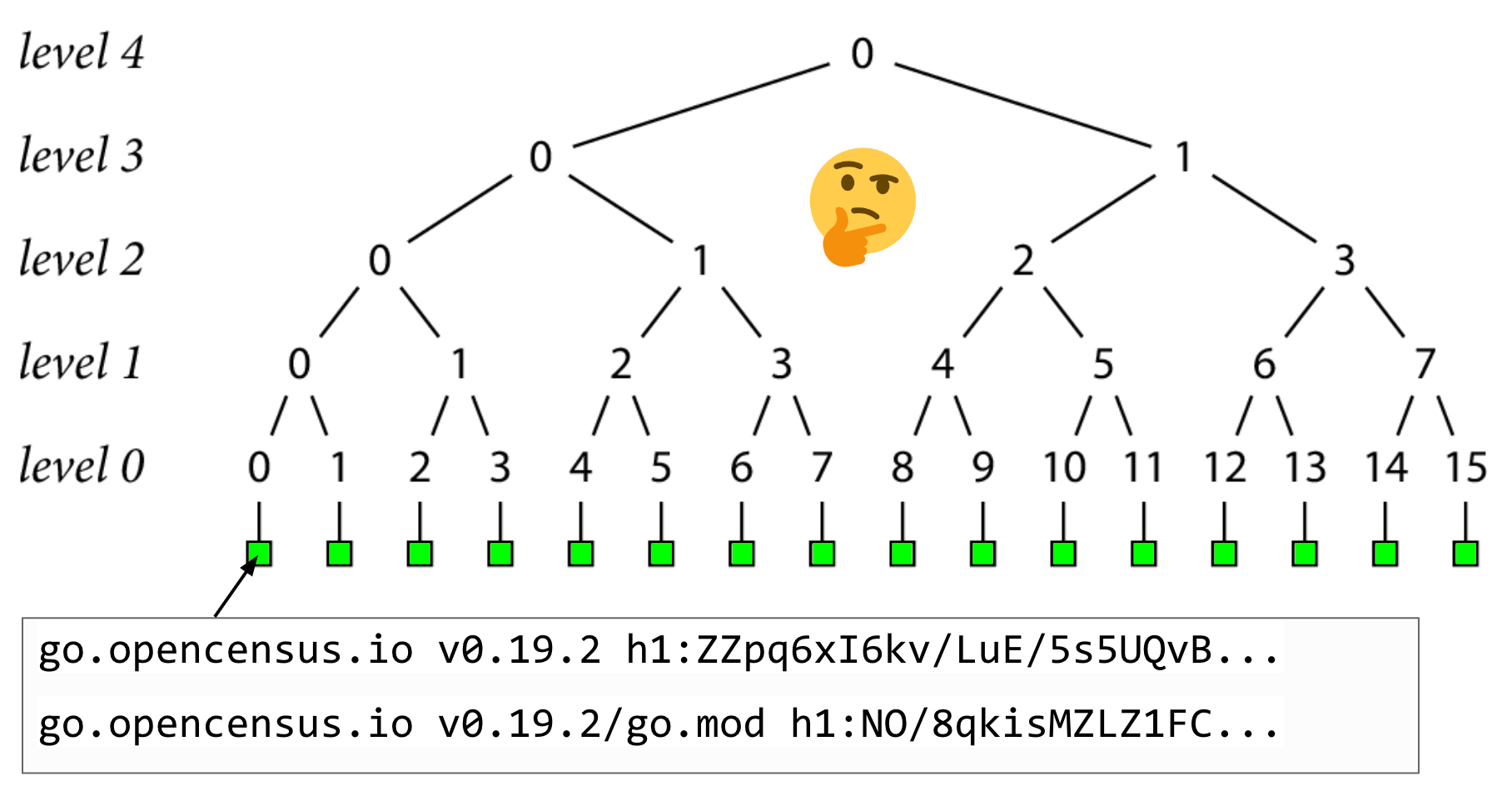

The foundation of our transparency log is the go.sum lines, indicated by the green boxes in this image.

Let's start by assuming that our log currently has 16 records.

tbdFor example, record 0 is the go.sum lines for go.opencensus.io at version 0.19.2. These are the only go.sum lines for this module version in the log, and the only go.sum lines the checksum database should serve. This is something that auditors can be in charge of verifying.

From here, we can start creating the rest of our tree.

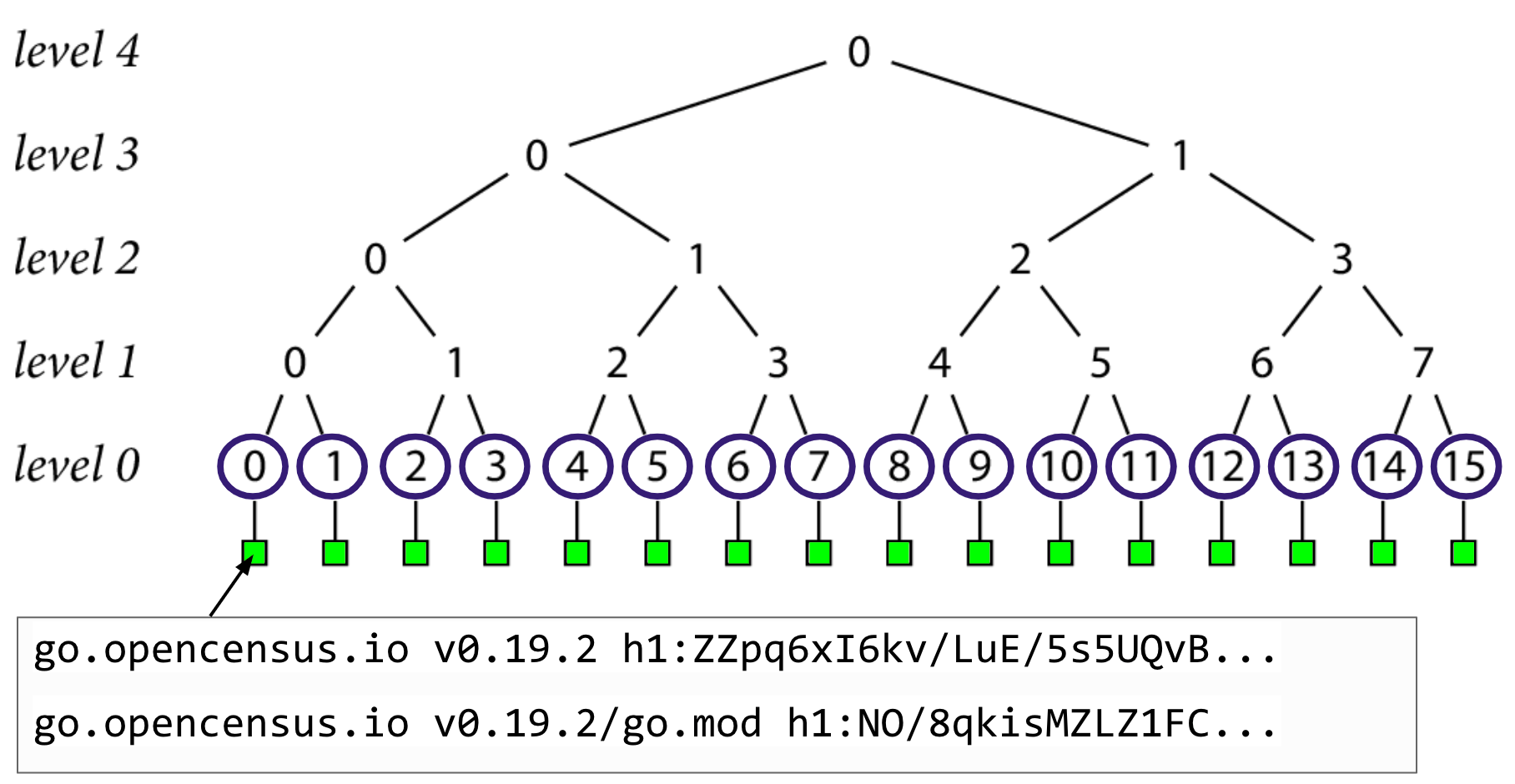

We do a SHA-256 hash of each record's go.sum lines, and store them as level 0 nodes.

Then we hash together pairs of level 0 nodes to create the level 1 nodes.

Then hash the pairs of level 1 nodes to create the level 2 nodes

And so on

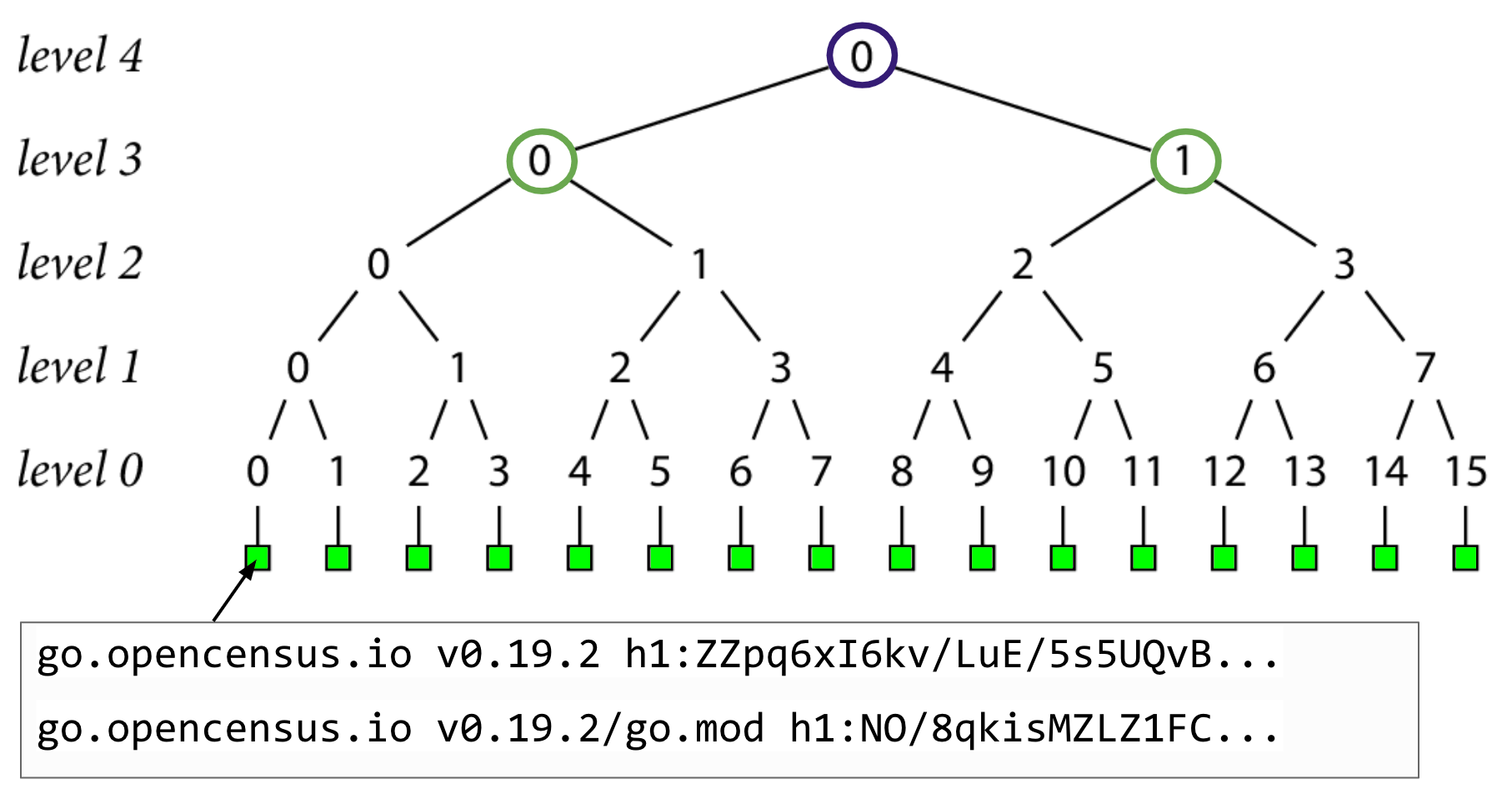

Until finally, we end up at level 4 in this example with a single hash at the top of the tree, which we'll call a tree head.

So why create hashes to begin with?

Well, remember those proofs she talked about? They basically boil down to comparing this top level tree head, or hash, and seeing if it matches up with those you've calculated and those you've seen before.

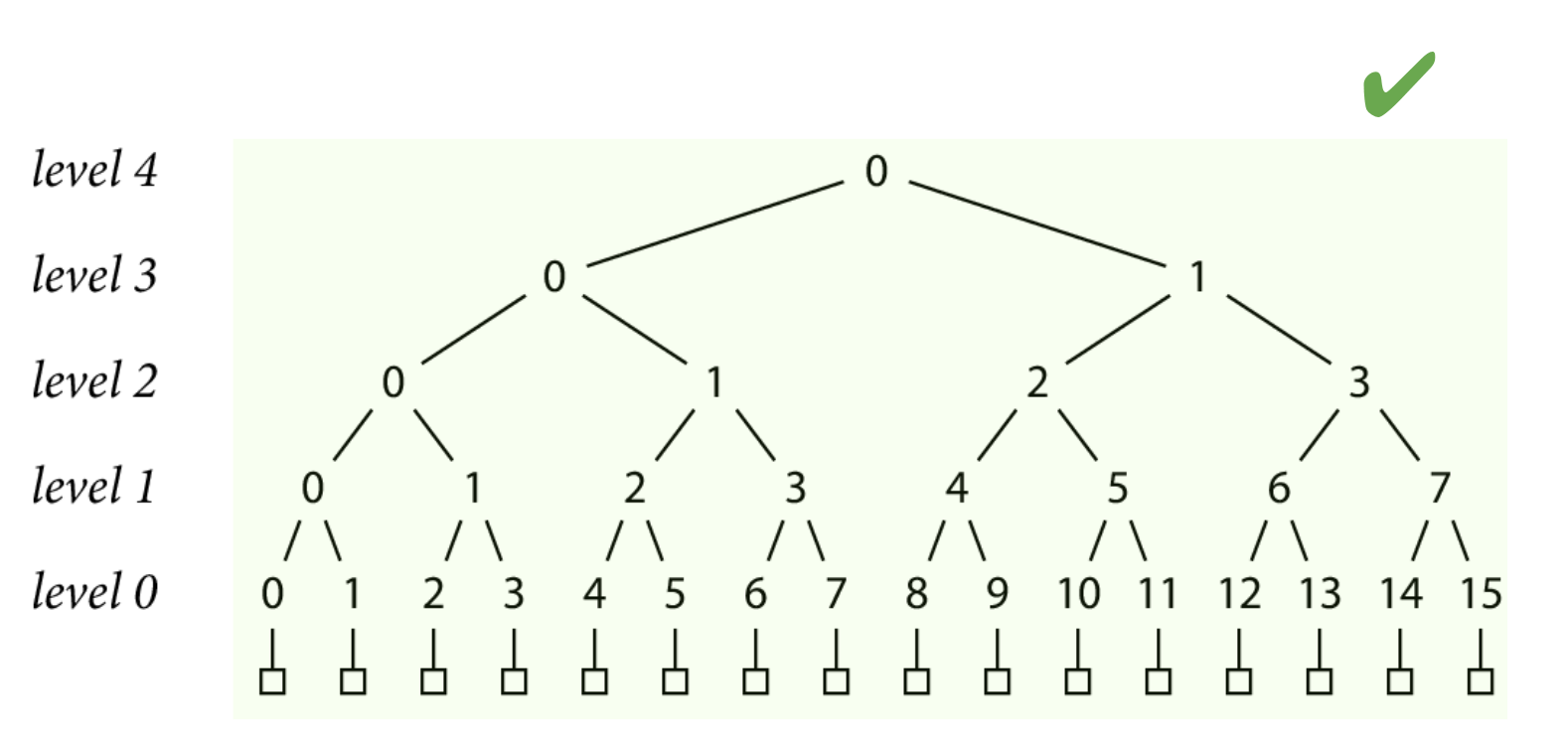

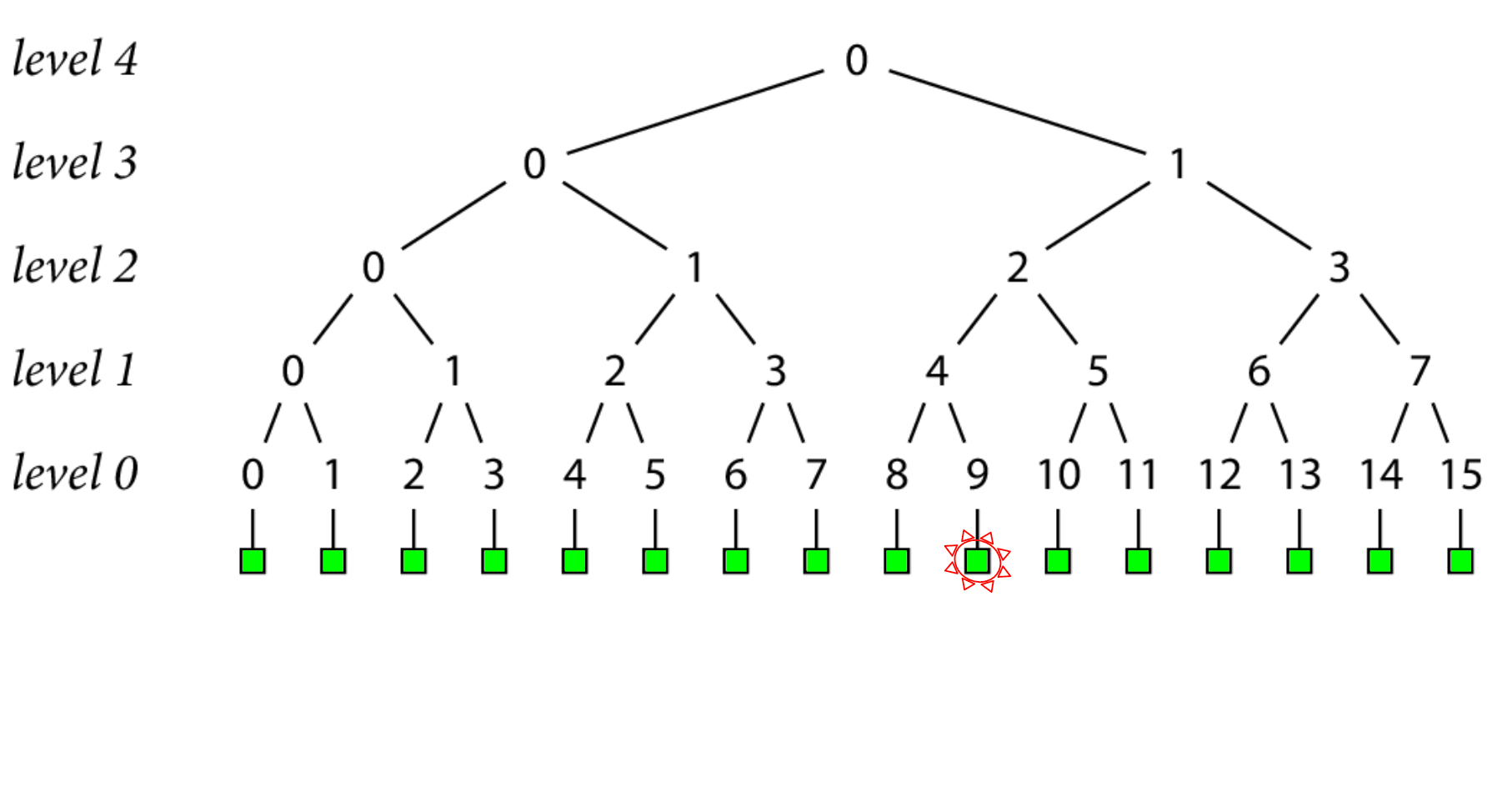

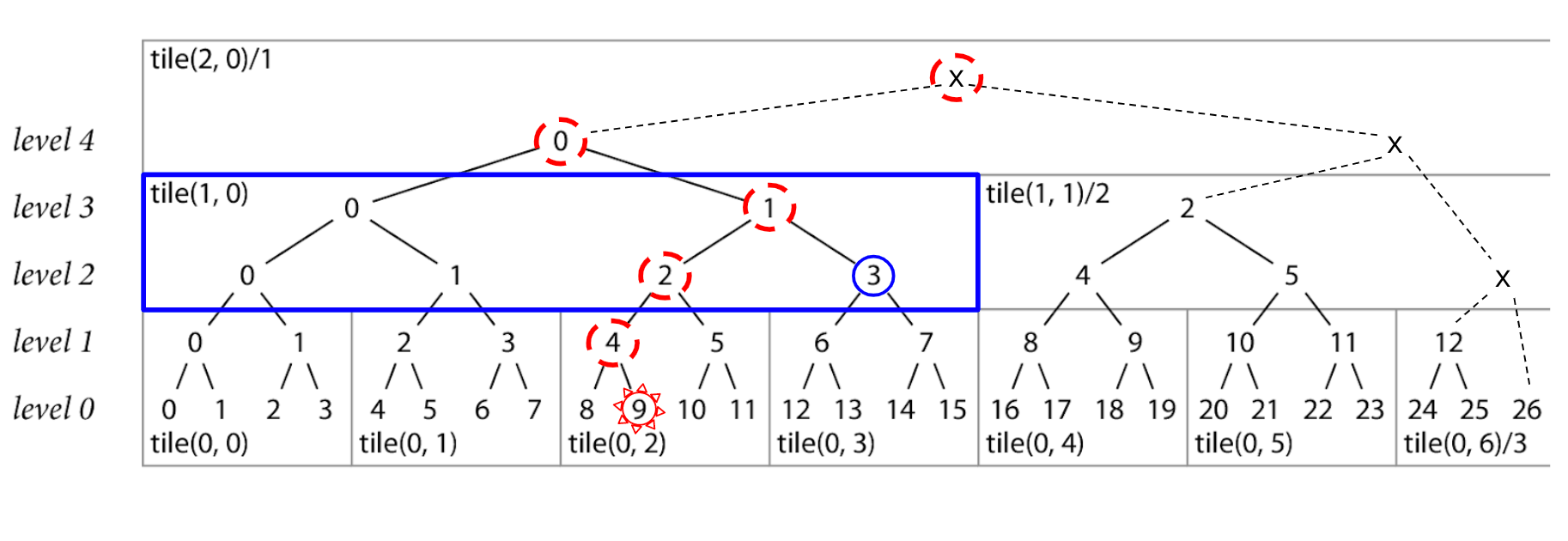

Let's go through an example of an inclusion proof, which only requires a few hashes to work. Proving that a set of go.sum lines are included in the tree is how the go command will verify the source code we just got back from a proxy.

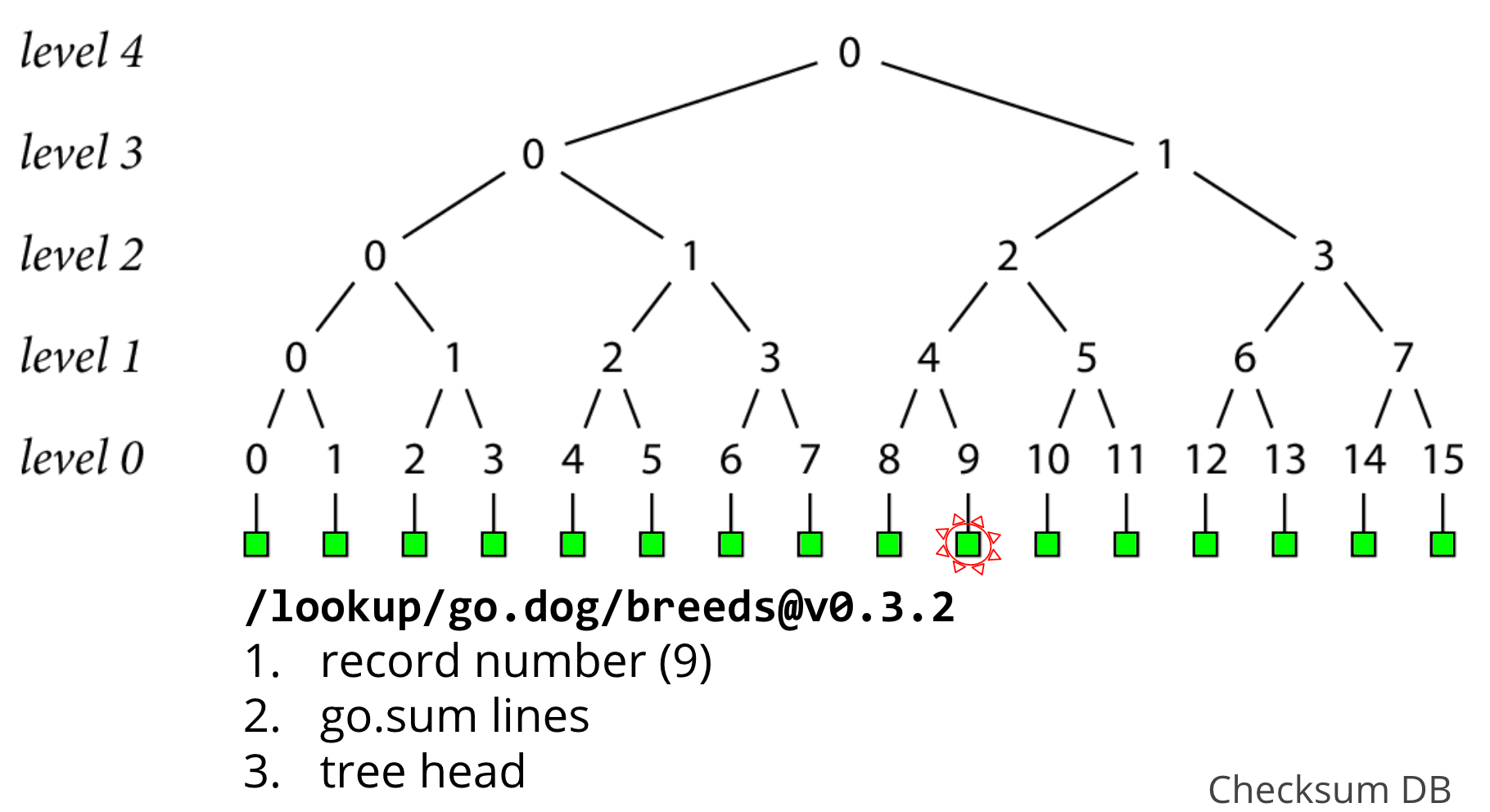

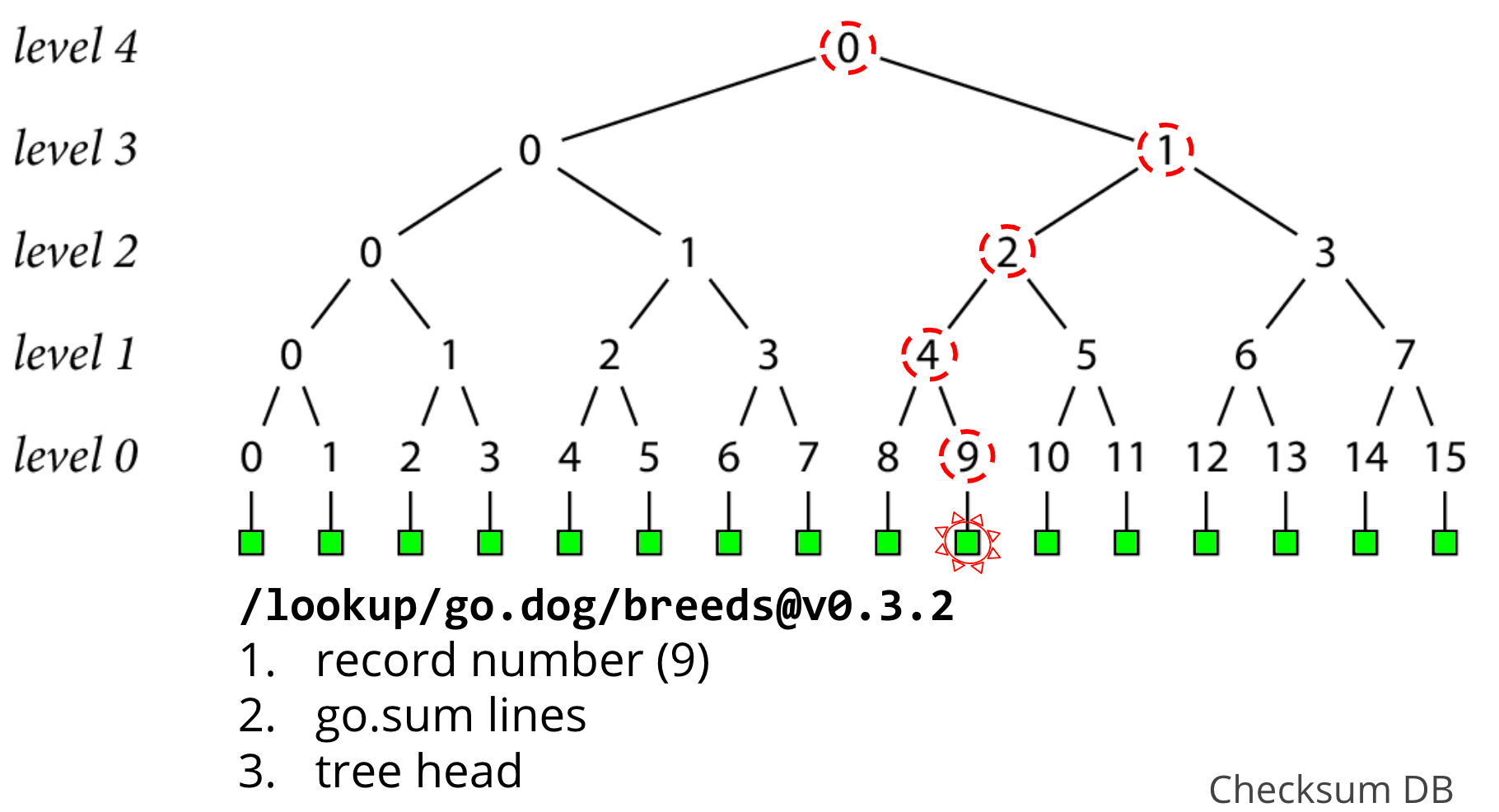

Let's say we want to verify the go.sum lines of go.dog/breeds at version 0.3.2 which we just fetched from a proxy, which in this example, just so happens to be record 9.

The first thing we'll do, is hit an endpoint on the checksum database called "lookup" with our module version, and it gives us back 3 things

- the unique record number that identifies it in the log, in this case, 9

- the go.sum lines for go.dog/breeds at version 0.3.2

- a tree head that contains this record

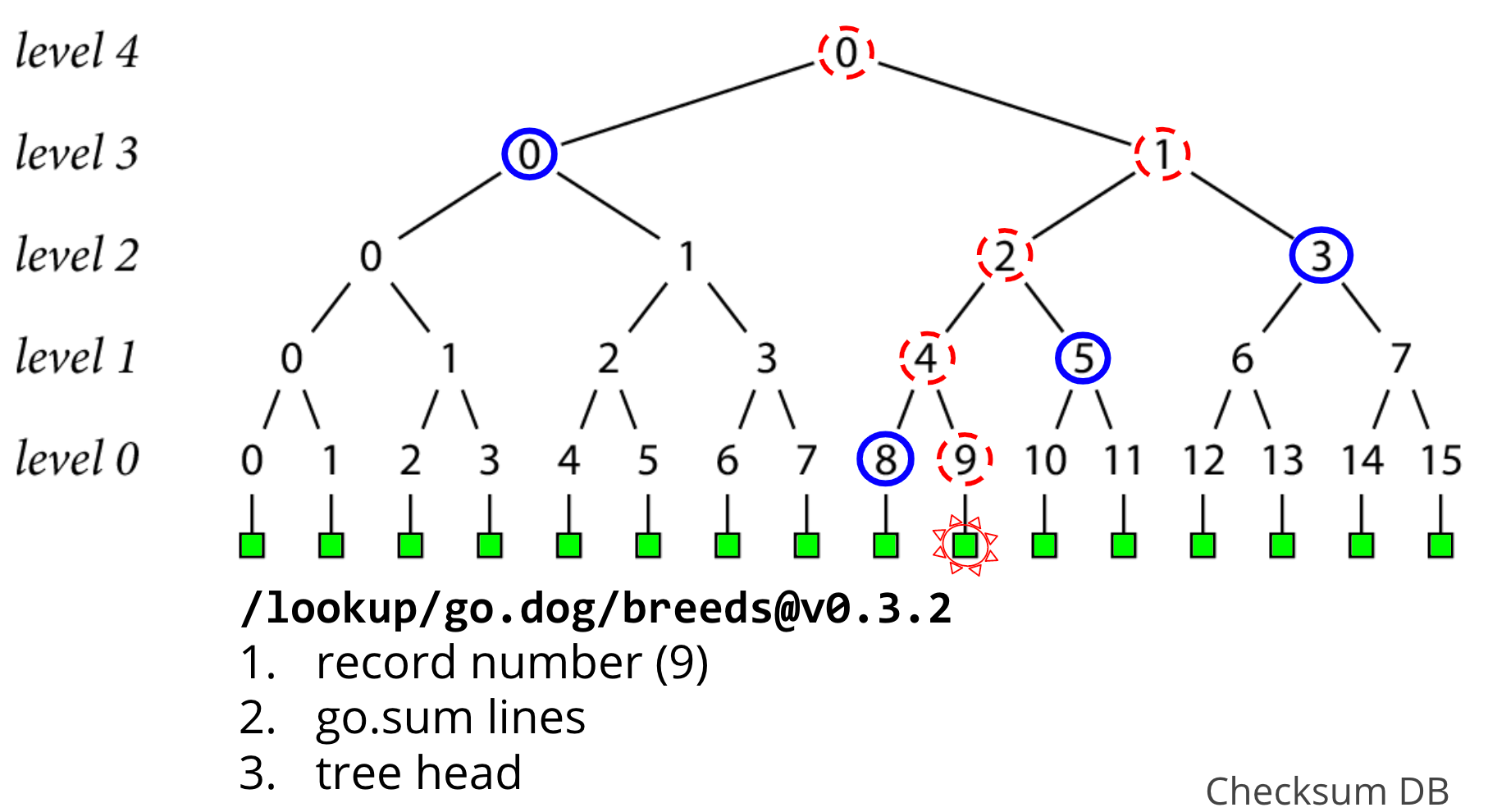

To prove that record 9 exists in the tree, we need to form a path from that leaf up to the head, and make sure its consistent with the head we were given. If we walk up by level in this example starting at level 0, that would nodes 9, 4, 2, 1, and 0 (the head at level 4).

The go command can create node 9 at level 0 by hashing the go.sum lines it was given , but it'll need some more nodes in order to create the rest of the path to head.

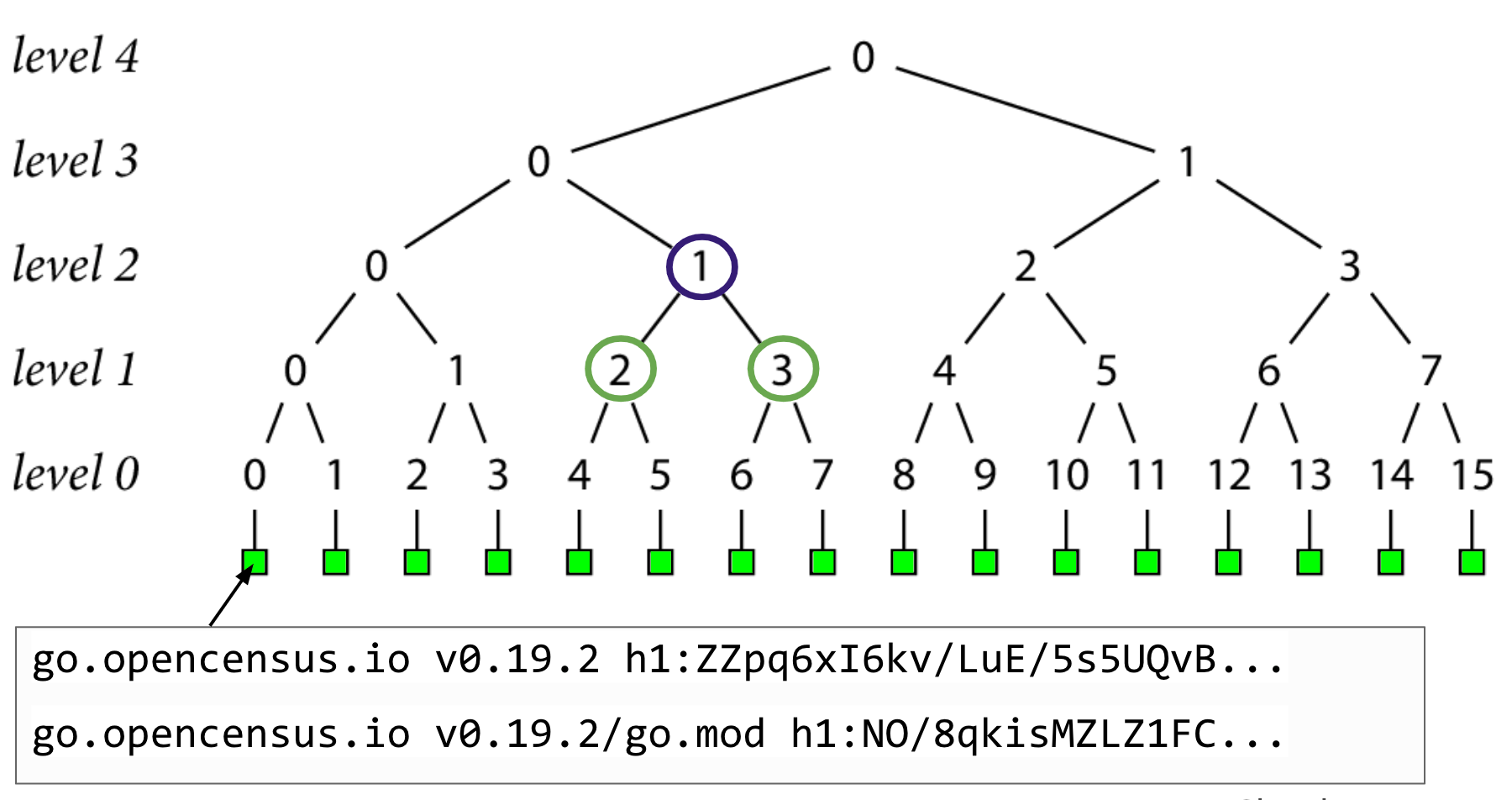

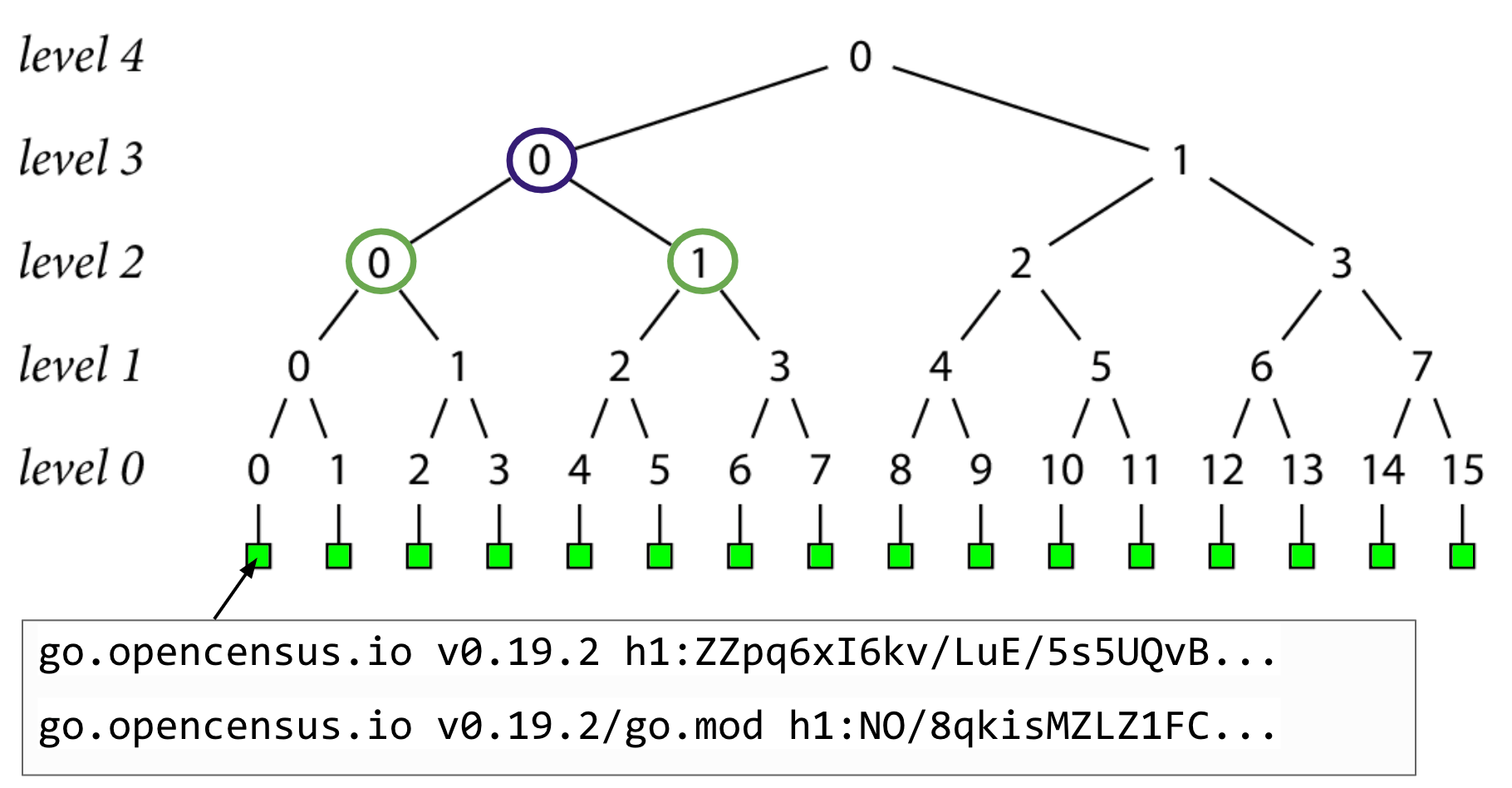

Here, in order to calculate the hash at node 4, we need to hash together nodes 8 and 9. Then, we can use that newly created hash at node 4 and hash it together with node 5 to create node 2, and so on , until we have the top level 4 hash.

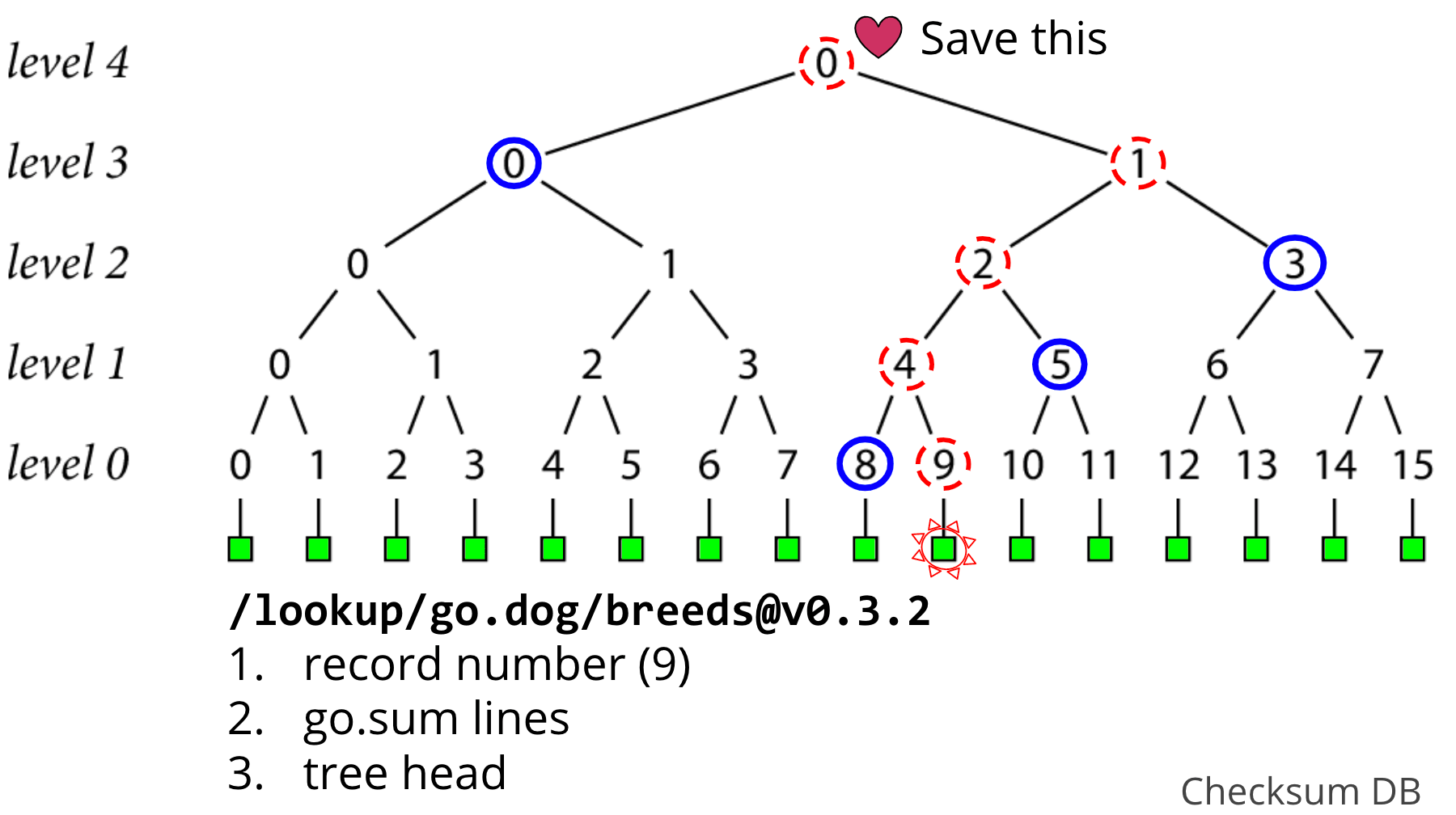

If this level 4 hash that we just created at the top of the tree is consistent with the tree head that we got back from the lookup endpoint, then we've done our inclusion proof, and verified the go.sum lines that we were looking for exist in our checksum database, and we're done!

As this tree grows, you'll get new tree heads, and you should check that these new trees are a superset of the old one. So the go command stores these tree heads as they are discovered, doing a consistency proof to verify that the new tree head it just found is consistent with the old tree head that it knew about before, to be sure the tree hasn't been tampered with.

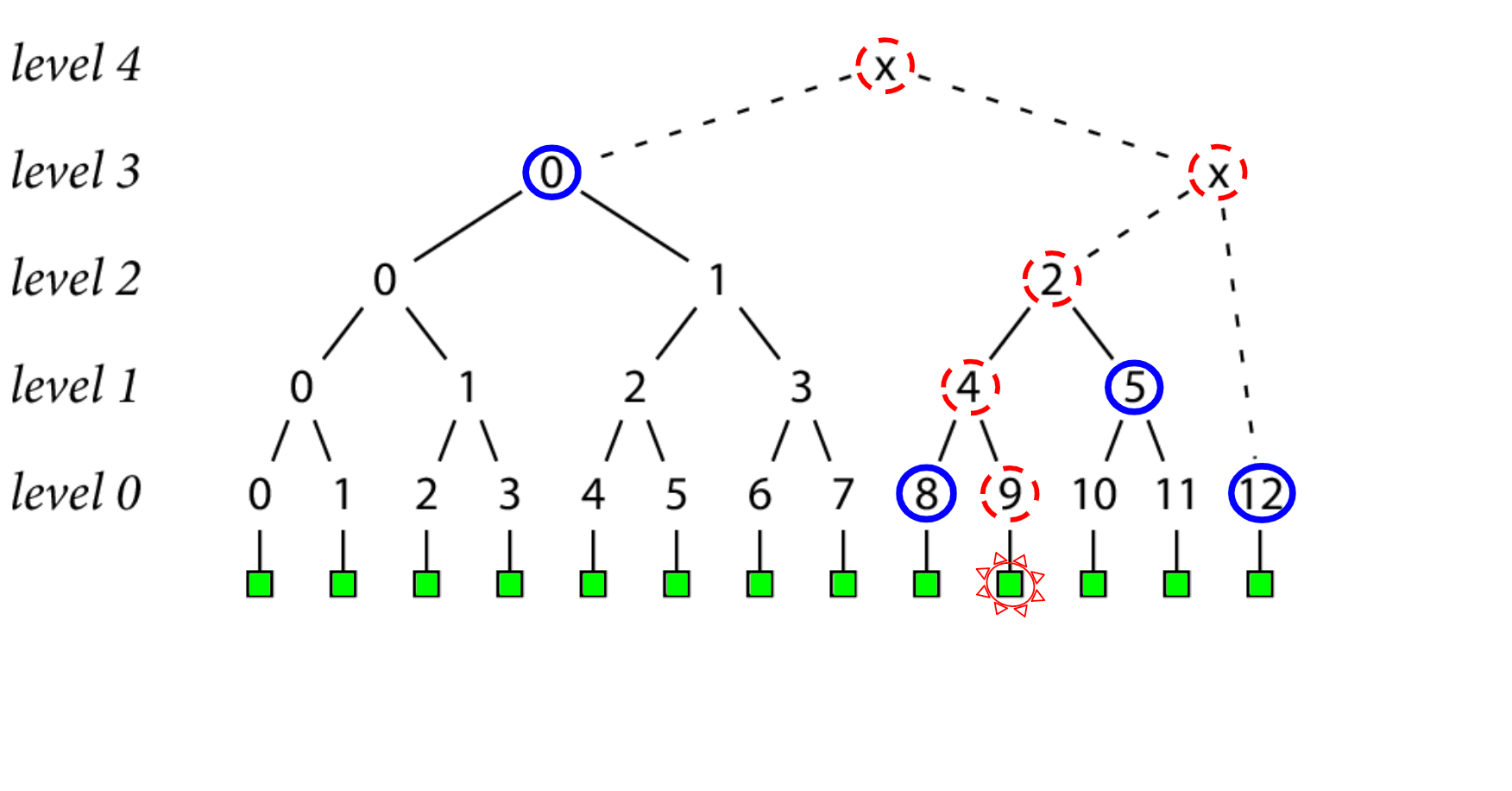

Oftentimes, the size of the tree won't be a power of 2, but we still want to be able to do our inclusion proofs in those cases. That's still possible!

In this example we have 13 records in our tree, which includes some "temporary" nodes, which are marked by x's in this diagram.

The only difference is that our path from leaf to head contains some temporary nodes that we need to create on the fly, that can be thrown away when we're done with them.

That's really all there is to the inclusion proof. In practice, the last thing we need to figure out is how to get these inner nodes circled in blue from the checksum database, in order to do our proofs.

And the way these inner nodes are stored and served are through something new, called a tile.

Under the hood, the checksum database breaks this tree apart into chunks called tiles. Each tile contains a set of hash nodes that can be used for proofs and accessed by clients.

In this example, we've chosen a tile height of 2, meaning that a new tile is created every two levels up the tree. The actual checksum database tree is much larger than this, so that uses a tile height of 8 in practice.

As an example of how the go command uses tiles, let's again look at our inclusion proof for record 9

We know that one of the nodes we'll need for this proof is node 3 at level 2, like before.

This node is contained inside of the tile(1, 0) so that's what the go command will request from the checksum database when doing it's proof.

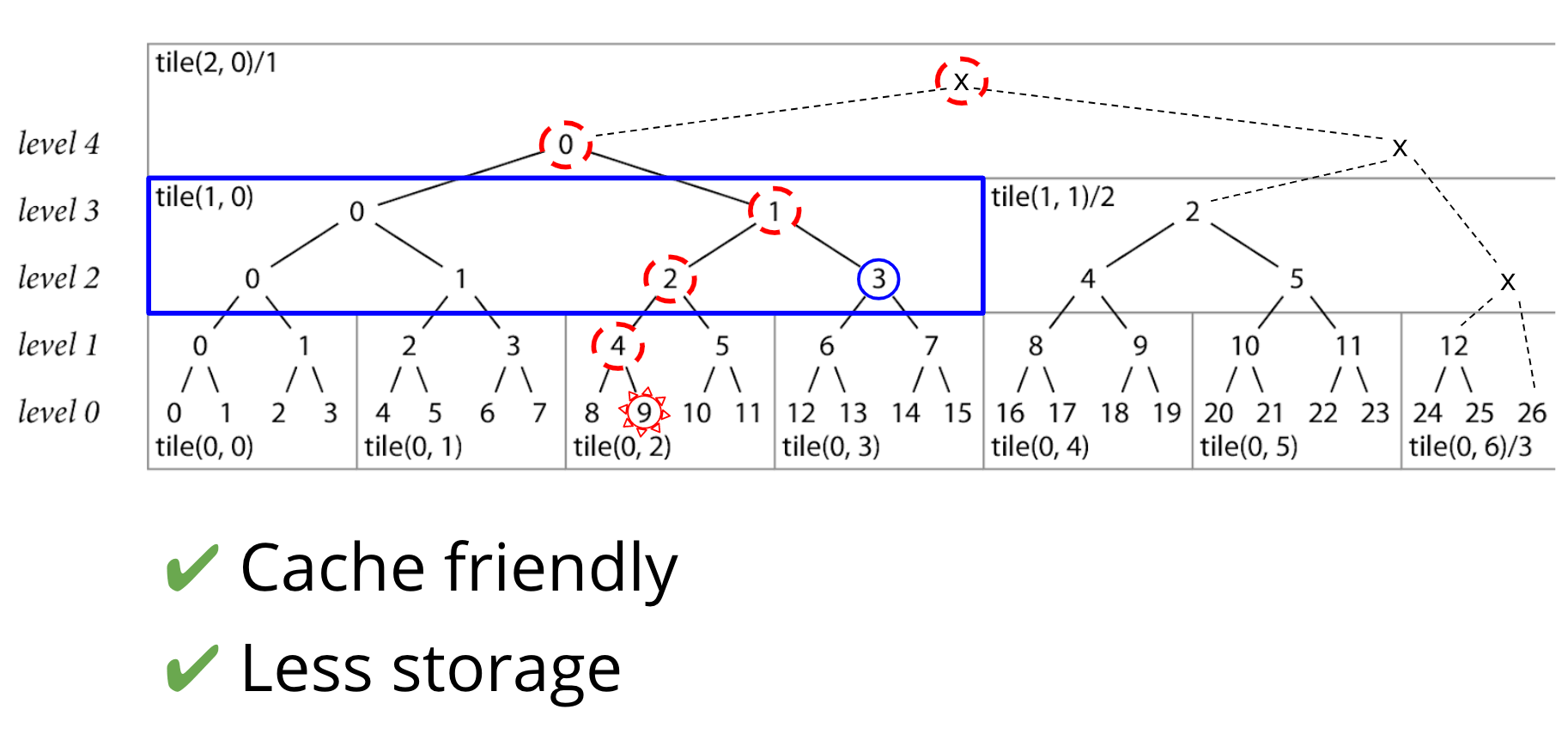

Using tiles has a few great benefits.

Tiles are nice for the checksum database server, since they are very cache-friendly at the frontend.

But it's also nice for the clients, because they only cache the bottom row of each tile, and build any necessary intermediate nodes from that. We've chosen a tile height of 8, so this cuts down on your storage costs. Instead of caching the entire tree, the go command is just caching every 8th level in the tree, and building inner nodes on the fly as needed.

Now that you've seen some of the math, let's get back to how it works within the context of Go.

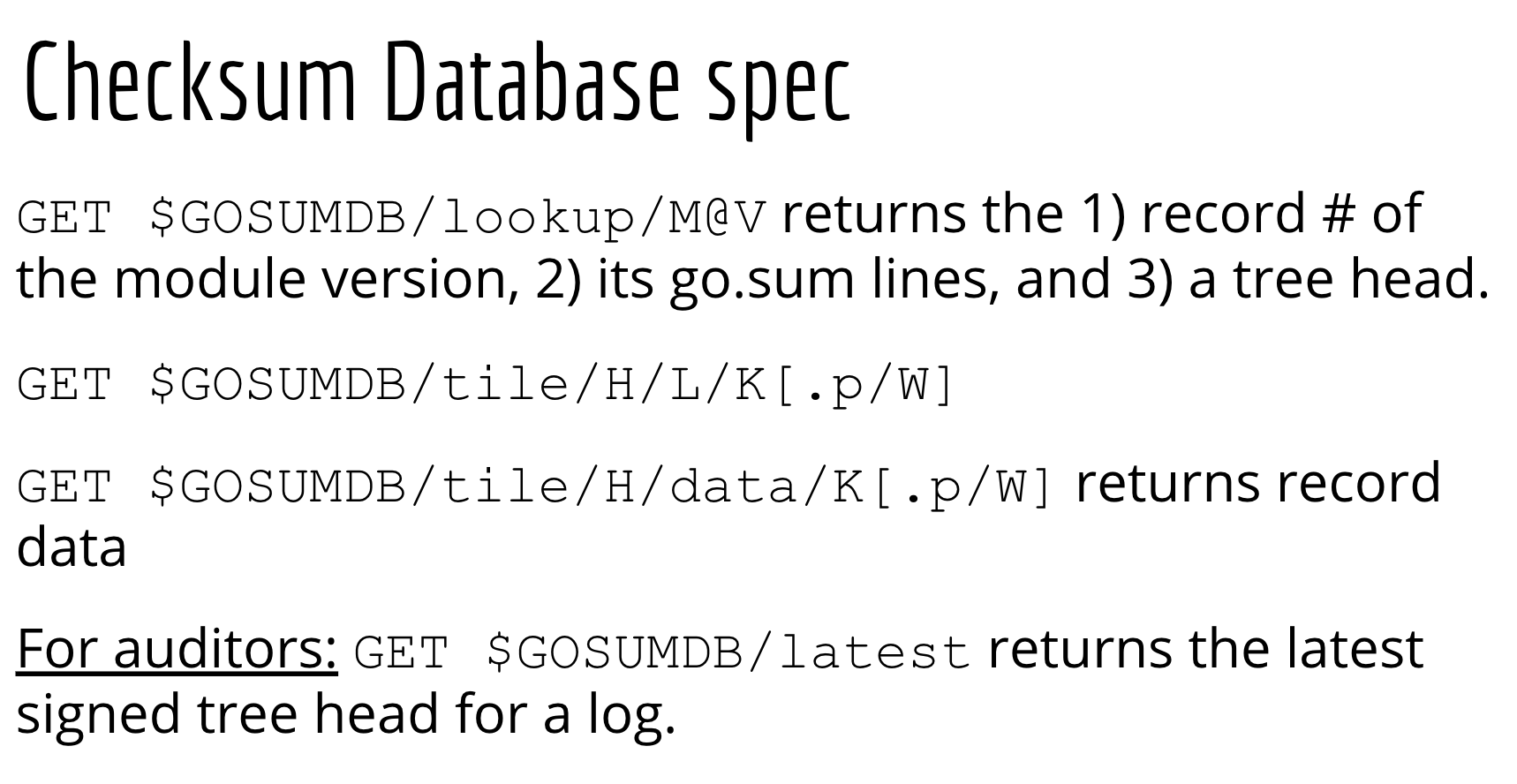

This tree is made available to the go command through the checksum database spec that you see here. It uses the lookup and tile endpoints to retrieve the data we just talked about.

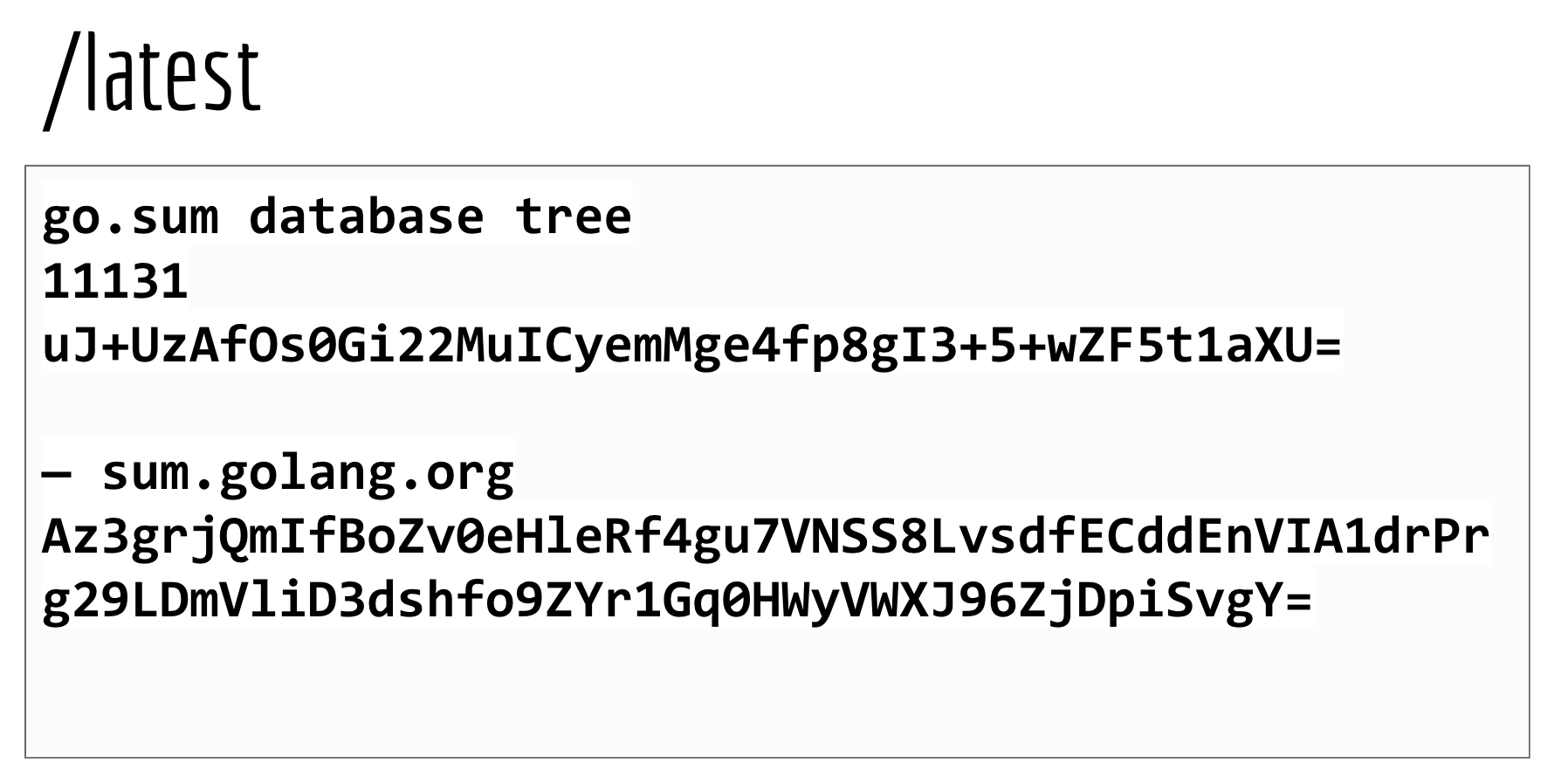

There is an additional endpoint, /latest, which serves the latest tree head that the checksum database has created. It is just used for auditors if they want to incrementally verify records based on the increasingly sized STHs that are provided.

A signed tree head looks something like this:

It tells you the size of the tree for this tree head, and it's hash value. In this example, the tree size is 11,131.

At the bottom is the signature, which contains the name of the checksum database, sum.golang.org, followed by its unique signature of that tree head. This signature is important, because it allows auditors to easily put the blame on sum.golang.org if it serves something it shouldn't have.

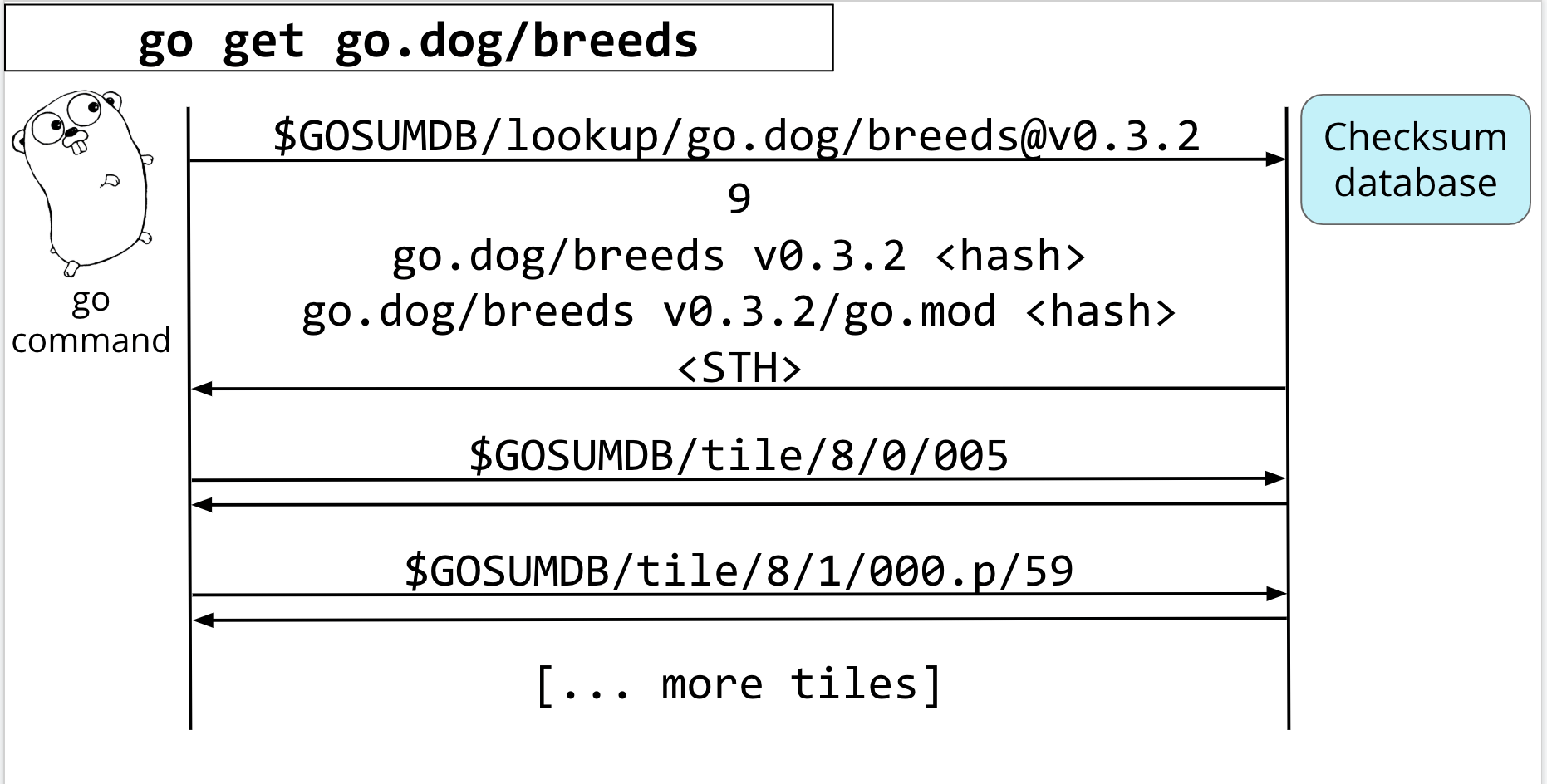

Let's go back to our example with the proxy. The last thing we did was fetch the zip of go.dog/breeds at version 0.3.2.

Before it updates your go.sum and go.mod file, it will make a hash, then check that this is the same hash that the checksum database has.

It'll start by doing a lookup of that module version

The checksum db gives back its record number, go.sum lines, and a signed tree head (or STH) that contains it.

Based on this record number and the records and tiles already cached and verified on your machine by the go command….

It can now start hitting the /tile endpoint to get the tiles it needs for its proofs.

Once the go command is done with it's proofs, it can update your module's go.sum file with the new go.sum lines, and we're done!

Now, instead of every person in the world individually trusting their first download of a module, the first version that the checksum database signs is the only one that is trusted. This ensures that the source code for a version of a module will be the same for every person in the world, since there is a single source of checksums to trust that can be verified and audited.

And this all works really well, even with just one checksum database that everyone uses. The community has the means of holding it accountable, and the go command does proofs on-the-fly as well, verifying that the checksum database hasn't been tampered with.

This checksum database is what makes untrusted proxies possible. A proxy can't start intentionally, arbitrarily, or accidentally start giving you the wrong code because there is an auditable security layer sitting in front of it before any source code reaches you.

If an origin server is hacked, then this will be immediately caught because we have an immutable checksum that identifies the contents when we first saw it.

Even the author of a module can't change move their tags around, changing the bits associated with a specific version from one day to the next.

And what's really nice about this, is that you as a developer don't have to do a single thing to make this work. You don't have to register your code anywhere in particular, you don't have to manage your own private keys or create your own hashes in a secure source. This checksum database creates the one and only hash for that code, and storing it in the log forever.

It's important to note that this checksum doesn't just solve a problem that proxies created. It actually creates a much safer user experience than the direct origin connections did, since it better protects you from changing dependencies and targeted attacks.

Now we have the full picture: Dependencies that are consistent, won't disappear, and can be trusted by everyone!

Fortunately, if these interest you, then she have good news for you. Katie and her colleagues on the go team have built a module mirror and checksum database that you can start using today.

Our module mirror and checksum database are used by default by the go command starting in Go 1.13 for modules-users. If you want to start using it today, simply upgrading to use the 1.13 beta is all you need to do.

Under the hood, the go command has a few environment variables that can be configured.

GO111MODULE and GOPROXY have been around since Go1.11.

You can set GO111MODULE to "on" to enable module mode everywhere or leave it at "auto".

You can set GOPROXY to a proxy of your choice to get picked up by the go command when in module mode. Though this has been around since 1.11, the ability to provide a comma-separated list is new for 1.13. This tells the go command to try multiple sources before giving up. If you want to use the Go team's module mirror, you can set it to https://proxy.golang.org.

The nature of the proxy and checksum database is that the source code has to be available on the public internet, so it can be audited and used by everyone. But if you're using private modules, you can disable the proxy and checksum database for the domains that you want to skip, by listing them in the GOPRIVATE environment variable.

She mentioned the open source project the Go team used for their transparency log.

They used Trillian for an implementation of the merkle tree data structure that she described earlier. They relied on their data store to hold the go.sum lines and corresponding hashes that the go command uses for its proofs.

We've talked about proxy.golang.org and sum.golang.org, but there is one more service that the Go team is providing in conjunction with these, a Module index.

index.golang.org is simple feed of new modules that have been discovered by proxy.golang.org](https://proxy.golang.org). You can see this feed at index.golang.org/index, and optionally provide a since parameter if you only want to view modules newer than a specific timestamp.

The Go team is really excited about the future of modules, providing a better dependency management experience to developers by creating reproducible builds, ensuring that dependencies won't disappear overnight, and making sure that the source code that you asked for is the source code that you and everyone else in the world gets every single time.

And she is personally happy, because now she has a set of solutions that can help her build out her module….

...which will make for happier puppies everywhere. :)

The Go team plans on fine-tuning these features, and they hope you'll try them out and give them feedback when you can! They'd love to hear how the mirror and checksum database are working for you, and we encourage you to file issues on GitHub as you spot them. The dogs of the world thank you.

Katie Hockman, Google, Go Open Source

Content provided by Katie Hockman's slide notes.