GopherCon 2019 - Better x86 Assembly Generation from Go

Dimitrios Arethas for the GopherCon 2019 Liveblog

Presenter: Michael McLoughlin

Liveblogger: Dimitrios Arethas

Overview

This talk will equip you with the tools to safely write lightning-fast assembly functions for Go. We will introduce Go assembly and the role it plays in the Go ecosystem, promote best practices for assembly development, and demonstrate how code generation tools can manage complexity in large assembly projects.

Summary

In this talk, Michael made a case for code generation techniques for writing x86 assembly from Go. Michael introduced us to assembly, assembly in Go, the use cases for when you would want to drop into assembly, and techniques for realizing speedups using assembly. He recognized that pure Go will be enough for 97% of us. However, there are 3% of cases where it is warranted. The examples he brought up were crypto, syscalls, and scientific computing. Michael then introduces us to a package called avo which makes high-performance Go assembly easier to write. Michael also makes the case that writing your assembly in Go will allow you to realize the benefits of a high level language such as code readability, the ability to create loops, variables, and functions, and parameterized code generation all while still realizing the benefits of writing assembly. Finally, he concludes the talk by stating his ideas for the future of avo.

Preface

This talk was technically dense, and a lot of detail was pointed out in the code. The information was presented on the slide and narrated as the transitions were occurring. As such, this makes liveblogging this sort of talk difficult. This liveblog captures the essence as well as the major points made. Please make sure to reference the slides available here: https://speakerdeck.com/mmcloughlin/better-x86-assembly-generation-with-go-gophercon-2019

Outline of the talk

- Go assembly primer

- Problem Statement

- Code Generation

- The avo library

- Examples

- Dot Product

- SHA-1

Assembly Language

What is assembly language? A low level language that allows programming at the architecture level.

Michael thinks of it as Layers in software that "tunnels all the way down." If you are writing assembly, then you are at the bottom.

Main question: Should you write assembly? Probably no.

Channel your inner Rob Pike: "Cgo Assembly is not Go. With the unsafe package assembly, there are no guarantees."

Channel your inner Donald Knuth: "about 97% of the time, premature optimazation is the root of all evil."

But, often the part of the Donald Knuth quote that is not included is "Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%"

The Critical 3%

The critical 3% is to take advantage of:

- missed opitmization by the compiler

- special hardware instructions

Common use cases:

- Math compute kernels

- System calls

- Low level runtime details

- Cryptography

The purpose of the talk is not to say don't use assembly, but if you are going to do it, do it safely and make use of as many tools as you can to make it safe.

Go Assembly Primer

package add

// Add x and y

func Add(x, y uint64) uint64 {

return x + y

}You can then run the Go disassembler on this code...

go build -o add.a

go tool objdump add.a...and check out the generated assembly instructions.

TEXT %22%22.Add(SB) gofile../Users/michaelmcloughlin/Dev...

add.go:5 0x2e7 488b442410 MOVQ 0x10(SP), AX

add.go:5 0x2e7 488b4c2408 MOVQ 0x8(SP), CX

add.go:5 0x2e7 4801c8 ADDQ CX, AX

add.go:5 0x2e7 4889442418 MOVQ AX, 0x18(SP)

add.go:5 0x2e7 c3 RETThe column on the far right is the interesting part. It is showing us the instructions.

package add

// Add x and y

func Add(x, y uint64) uint64When the build system sees this version of the Add function (without the function body), it expects to see an assembly implementation in another file.

#include "textflag.h"

// func Add(x, y uint64) uint64

TEXT ·Add(SB), NOSPLIT, $0-24 <-- Declaration

MOVQ x+0(FP), AX <-- Read X from stack frame

MOVQ y+8(FP), CX <-- Read Y

ADDQ CX, AX <-- Add X and Y together

MOVQ AX, ret+16(FP) <-- Write return value

RETThe assembly definition starts with the TEXT line.

The 24 value in the TEXT line is there because it takes two 64-bit values (or 8 bytes) and returns a 64-bit value, totaling 24 bytes

Then Every function is going to start with some MOV instructions, and all arguments are passed to us on the stack.

Problem Statement: what can go wrong?

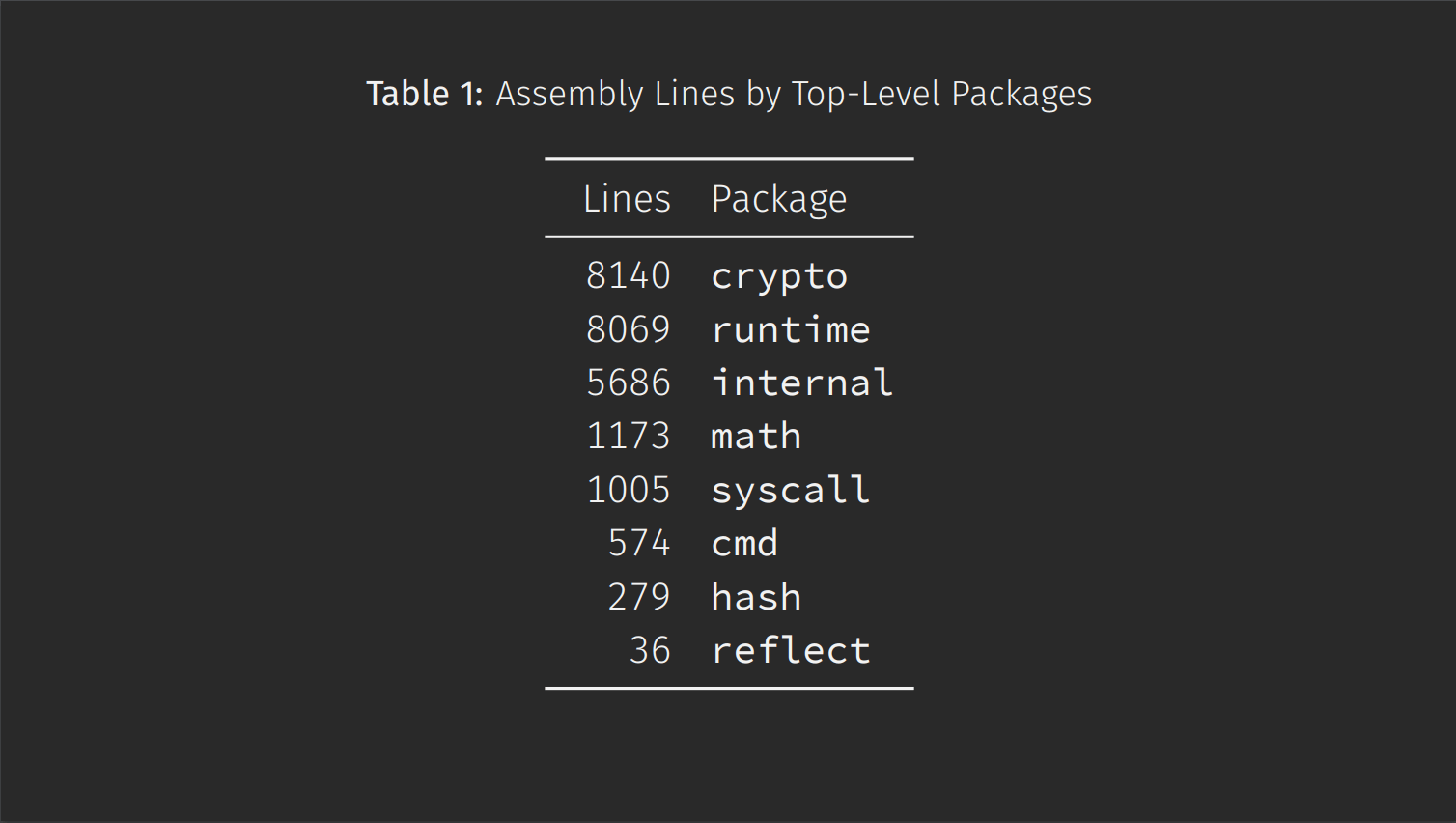

24,962: the number of lines of x86 assembly in the standard library. If we were to include other architectures, this number would be quite a bit higher.

Crypto is the heavy hitter here. Crypto is also in this awkward intersection where you need top performance, but you need complete correctness. Any error could lead to a critical security vulnerability.

Drilling down even further into some code in the crypto package (There is no expectation that the code is understood, it is just to give a feel for the problem Michael is talking about)

openAVX2InternalLoop:

// Lets just say this spaghetti loop interleaves 2 quarter rounds with 3 poly multiplications

// Effectively per 512 bytes of stream we hash 480 bytes of ciphertext

polyAdd(0*8(inp)(itr1*1))

VPADDD BB0, AA0, AA0; VPADDD BB1, AA1, AA1; VPADDD BB2, AA2, AA2; VPADDD BB3, AA3, AA3

polyMulStage1_AVX2

VPXOR AA0, DD0, DD0; VPXOR AA1, DD1, DD1; VPXOR AA2, DD2, DD2; VPXOR AA3, DD3, DD3

VPSHUFB ·rol16<>(SB), DD0, DD0; VPSHUFB ·rol16<>(SB), DD1, DD1; VPSHUFB ·rol16<>(SB), DD2, DD2; VPSHUFB ·rol16<>(SB), DD3, DD3

polyMulStage2_AVX2

VPADDD DD0, CC0, CC0; VPADDD DD1, CC1, CC1; VPADDD DD2, CC2, CC2; VPADDD DD3, CC3, CC3

VPXOR CC0, BB0, BB0; VPXOR CC1, BB1, BB1; VPXOR CC2, BB2, BB2; VPXOR CC3, BB3, BB3

polyMulStage3_AVX2

VMOVDQA CC3, tmpStoreAVX2

VPSLLD $12, BB0, CC3; VPSRLD $20, BB0, BB0; VPXOR CC3, BB0, BB0

VPSLLD $12, BB1, CC3; VPSRLD $20, BB1, BB1; VPXOR CC3, BB1, BB1

VPSLLD $12, BB2, CC3; VPSRLD $20, BB2, BB2; VPXOR CC3, BB2, BB2

VPSLLD $12, BB3, CC3; VPSRLD $20, BB3, BB3; VPXOR CC3, BB3, BB3

VMOVDQA tmpStoreAVX2, CC3

polyMulReduceStage

VPADDD BB0, AA0, AA0; VPADDD BB1, AA1, AA1; VPADDD BB2, AA2, AA2; VPADDD BB3, AA3, AA3

VPXOR AA0, DD0, DD0; VPXOR AA1, DD1, DD1; VPXOR AA2, DD2, DD2; VPXOR AA3, DD3, DD3

VPSHUFB ·rol8<>(SB), DD0, DD0; VPSHUFB ·rol8<>(SB), DD1, DD1; VPSHUFB ·rol8<>(SB), DD2, DD2; VPSHUFB ·rol8<>(SB), DD3, DD3

polyAdd(2*8(inp)(itr1*1))

VPADDD DD0, CC0, CC0; VPADDD DD1, CC1, CC1; VPADDD DD2, CC2, CC2; VPADDD DD3, CC3, CC3

internal/x/.../chacha20poly1305_amd64.s lines 856-879 (go1.12)Nothing with the words "spaghetti loop" in it instills any confidence. This is really write once code in Michael opinion. If you were presented with this in a code review, where would you start?

So naturally, one might find themselves asking,

Is this fine?

Much of this code is written by world experts in cryptography and performance and we are lucky to have these people in the Go community. It probably is fine. But maybe it is worth looking at.

TEXT p256SubInternal(SB),NOSPLIT,$0

XORQ mul0, mul0

SUBQ t0, acc4

SBBQ t1, acc5

SBBQ t2, acc6

SBBQ t3, acc7

SBBQ $0, mul0

MOVQ acc4, acc0

MOVQ acc5, acc1

MOVQ acc6, acc2

MOVQ acc7, acc3

ADDQ $-1, acc4

ADCQ p256const0<>(SB), acc5

ADCQ $0, acc6

ADCQ p256const1<>(SB), acc7

ADCQ $0, mul0

CMOVQNE acc0, acc4

CMOVQNE acc1, acc5

CMOVQNE acc2, acc6

CMOVQNE acc3, acc7

RET

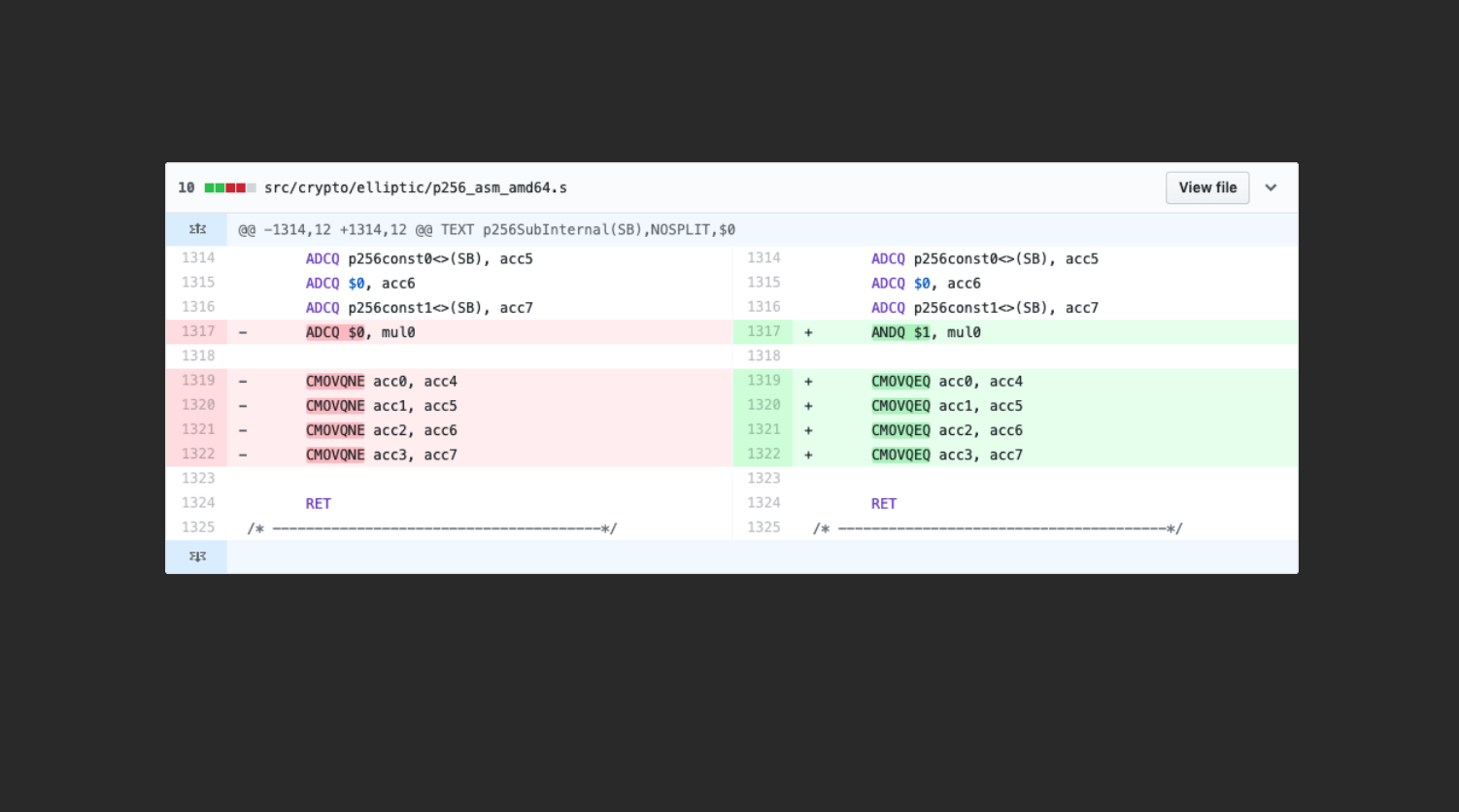

crypto/elliptic/p256_asm_amd64.s lines 1300-1324 (94e44a9c8e)Above is some code from the standard library

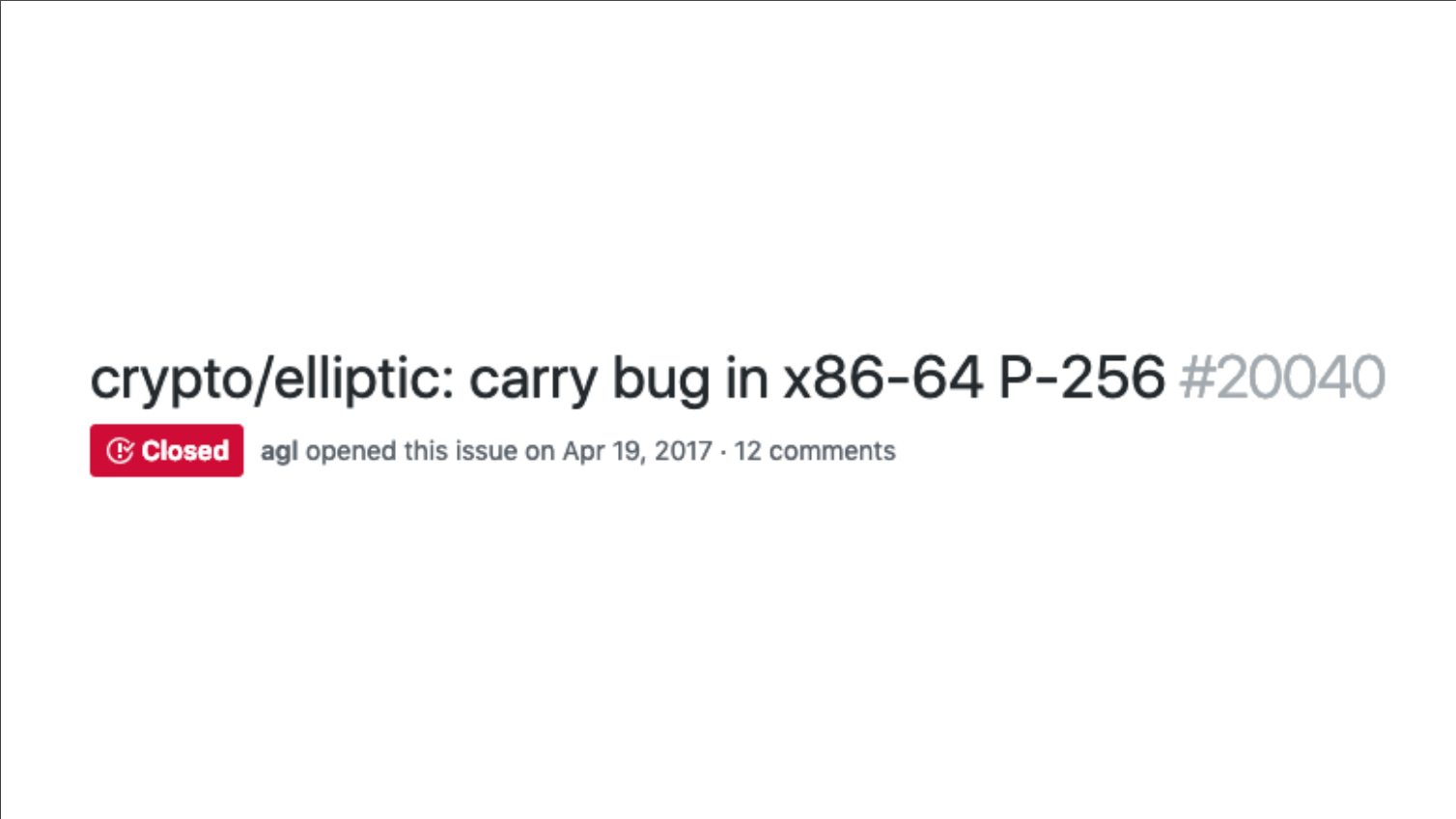

Around 2 years ago Cloudflare discovered a bug that involves a carry, it happens 1 in 4 billion, but Cloudflare operates at such a scale that it experiences this.

The fix is just 5 lines. It was origially just believed to be just a compatibility issue.

But actually it was later discovered to be a critical vulnerability. This critical error could be exploited to leak secure information.

So is there anything else hiding in this 8 thousand lines of assembly?

And the Go team itself seemed to have agreed. Around a year ago, they created a Go Assembly policy.

-

Prefer Go, not assembly

-

Minimize use of assembly

- Restricted to just the bottleneck

-

Explain root causes

- Have commit messages explaining it

- any information that may warrant removing it in the future

-

Test it well

-

Make assembly easy to review

The last rule listed is something Michael wants to focus on: "When I heard this I took it as a mission statement."

Code generation is a tool people have used for many years to manage this type of complexity. There is a reason people use compilers. Just because we are deciding to write assembly doesn't mean we should throw away all these niceities.

C has something called Intristics where each of these function compiles down to just a single instruction. Unfortunately, we can't do this in Go.

There is also High level assembler. Assembly language plus high level language features. These have the concepts of if statements and loops to add structure to your assembly.

OpenSSL is obviously another package that has a lot of assembly, and they use Perl of all things, which is a pretty shocking combination of languages.

There is a great package called PeachPy which is a python-based high level assembler.

But it feels a little bit dirty to use Python in Go projects, so Michael thought to himself, "What about Go?" and set out to create a solution

When you are using this package it should feel like you are writing assembly, but you are actually writing a Go program.

Non-goals of the avo project:

- not a compiler: it should be close to assembly.

- not an assembler

The programmer retains complete control. Anything that can be done in assembly can be done in this package, but the goal is to remove some of the tedium, or repetition.

An Avo program is a Go program. You can structure your assembly using functions, loops, conditionals.

Michael thinks one of the killer features is it contains a register allocator. You can write your functions using virtual registers and avo assigns physical registers for you. You can also use variable names that mean something to you so that your code is more readable.

Avo also handles the details of automatically computing memory offsets.

Additionally it autogenerates stub files so we can call our assembly functions from our Go packages.

Michael then goes through the library. In particular, the dot product example, which using avo to generate assembly allows you to take advantage of special hardware instructures such as "FMA" (Fused-Multiply-Add) instructions like VFMADD231PS which allows you to perform 8 single-precision FMAs.

In the end, the SHA-1 example was 116 avo lines which translated to about 1500 assembly lines, and showed how using a library like avo can make your assembly easier to write, read, and maintain.

Michael then finishes with some goals and directions avo could go in the future:

- Simply to use avo in real projects, specifically large crypto implementations to show how it can be simplified.

- More architecture support

- Possibly make avo an assembler itself

- these kinds of techniques are used in JIT compilers so could be a natural direction

- avo based libaries

- avo/std/math/big

- avo/std/crypto

Parting words

I hope you learned something about assembly, and I hope that assembly isn't quite so scary anymore, and if you consider using it in your project, you will try and use avo.